For all but the most starry-eyed devotees, or family members, of an aspirant to public service, voting essentially boils down to deciding which evil is lesser.

Well, that’s a bit harsh. What I mean is that it’s nearly impossible for any candidate to fit the full bill of any voter’s list of qualifications and preferred positions on all matters of importance. One aspirant to public office may have a preferable economic plan but a dismal approach to immigration or security matters; another may be on the right page regarding social issues but on a very wrong one when it comes to geopolitical ones. And then there are important other factors in play, like intelligence, honesty, gentility and likeability (or their absenses).

If polls and man-in-the-street interviews are any indication, in the presidential election that is rapidly (and blessedly) soon coming to an end, the “lesser evil” calculus seems particularly pertinent. Both candidates’ negative ratings are, well, impressive.

Many factors might be blamed for that state of affairs, and for the general deterioration of American political campaigning. A prominent one is money.

Hundreds of millions of dollars have been raised to feed each of the current candidates’ cash-famished campaigns. And were a dollar equivalent to be assigned to the free airtime garnered by one candidate’s propensity to make attention-getting pronouncements, he (oh, shucks, I gave it away) has effectively either paid or received the equivalent of over a billion bucks.

Most complaints about the role of money in political campaigns revolve around the undue influence wielded by a relatively small group of very wealthy individuals. And it’s a valid concern. A mere 250 donors accounted for about $44 million in contributions to the Hillary Victory Fund during the last year.

The billionaire oilman T. Boone Pickens has boasted that he “won the election in 2004 for Bush.”

In the 2012 election season, Charles and David Koch, who own the lion’s share of the second-largest privately held company in the United States, pledged $60 million to defeat Barack Obama. Of $274 million in anonymous contributions that year, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics (CRP), at least $86 million came from “donor groups in the Koch network.”

In 1996, according to the CRP, the two major parties spent $448.9 million on the general election; in 2012, they spent $6.3 billion.

The republic’s founding fathers envisioned government as emerging from the consent of the governed, not the gvirim.

Then there is the toll taken by the fact that fundraising – in 2010, candidates for Congress spent $1.8 billion in their bids for office – has become a way of life for elected officials, swallowing up time and effort that could otherwise have been spent doing, well, what those legislators were elected to do.

Even more disturbing, at least to this decidedly apolitical observer, is what the money actually does. How, in other words, does a mega-stuffed campaign chest translate into mega-votes?

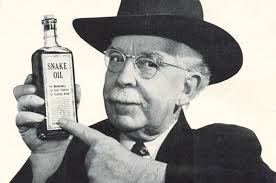

The answer is that cash can capitalize on ignorance.

Most voters, unfortunately, are far from conversant with the intricacies of issues, even those that they may care about the most. The average citizen finds calculations and thinking more than a step or two ahead to be boring endeavors, and more readily responds to appeals to emotions – good, bad and ugly ones alike.

A large chunk of political contributions goes to crafting and making those appeals. And so, political ads and mail pitches– no different in any way from those that make people buy particular brands of shampoos, beer or automobiles based on imagery and fantasy rather than quality – have become proven tools for effectively translating dollars into votes.

“Buying votes” used to mean ward bosses offering cash to individuals for their pledge to cast their ballots a certain way. Times have changed, though. Today, vote-buying is accomplished less sleazily, though no less ignobly.

In a saner democracy, there would be no campaign ads at all, only the presentation of detailed positions on issues of importance. Candidates would write manifestos, not lob accusations and insults. Debates, if we had them at all, would be strictly limited to issues, with candidates arguing the virtues of their respective goals and policies. Boasting, insulting, punching and counterpunching would be relegated to boxing rings, whence they came. (Actually, boxing is another blood sport the world would be a better place without.)

Alas, the Shafran System of Democratic Electioneering has about as much a chance at being adopted as Gary Johnson has of being elected president this November.

Still, one can fantasize, no?

© 2016 Hamodia