A Roman emperor, according to a Midrashic account (Sifri, Devarim 357), sent two army units to find Moshe Rabbeinu’s burial site. When they stood above it on a hill, they saw it below. When they descended the hill, they saw it above them.

“So, they split up, half above and half below; those above saw it when they looked down, and those below saw it when they looked up.” But neither group could reach the grave.

Which reflects the Torah’s text “No one knows his burial place to this day” (Devarim 34:6).

The space warping recalls that of the aron in which Moshe’s luchos lay.

Rabi Levi (Yoma 21a) notes a mesorah that “the place of the aron is not included in the measurement” – that the kodesh hakadashim measured twenty amos by twenty amos, yet a beraisa states that there were ten amos of space on either side of the aron.

It was there, to be sure, but took up no space.

And Moshe’s grave exists but flips in and out of space.

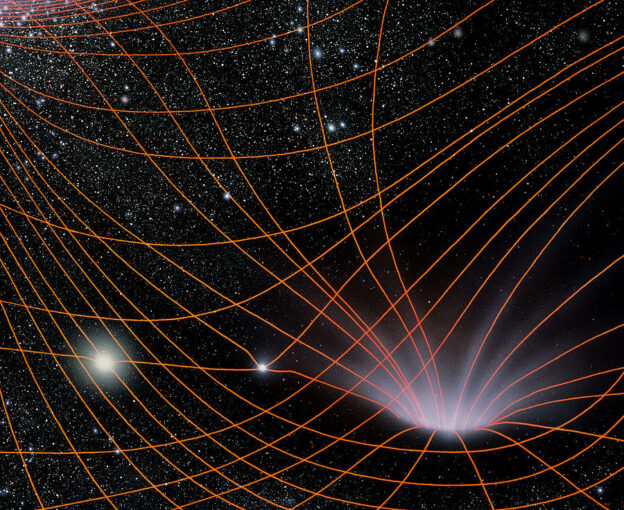

The idea that space is a given, and cannot be interrupted or bent in any way, was the dominant scientific assumption… until Einstein. Today we know that space, like time, is not a simple unchangeable grid. It can be warped, even torn. And the fact that the assigned place of the Law and the final resting place of the G-d-sent human Lawgiver don’t “fit” space as we know it may mean to telegraph the truth that the Torah, while it was given us in our cozy, seemingly three- (or four, counting time) dimensional universe, encompasses it but exists outside it.

It’s a fitting thought as we transition to the beginning of the Torah, where the first pasuk states that “heaven and earth” were brought into being. Or, as a modern astrophysicist might put it, that space and time themselves came to be, expanding from an unknowable singularity into what we call our universe.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran