It’s bad enough that the person whose divisive sins caused him to contract tzora’as (a physical condition conferring tum’ah and sometimes mistakenly identified with leprosy) has to sit apart from society, but he is also enjoined: “vi’tamei tamei yikra” — “ ‘And ritually contaminated! Ritually contaminated!’ he should call out” (Vayikra 13:45).

Indeed, the Talmud uses that added indignity to illustrate a popular (well, at the time) saying: “Poverty follows the poor.” (Bava Kama, 92b).

But the metzora’s prescribed announcement of his condition, says the Talmud, teaches other things too. Like the importance of letting others know of one’s sufferings, so that they might pray for him (Mo’ed Katan 5a). And it hints, too, to the need to mark a grave, so that people won’t inadvertently become tamei by passing over it (ibid).

The Shelah (Rav Yeshayahu HaLevi Horovitz, c.1555-1630), however, sees in the metzora’s announcement a hint to yet something else. Parsing the phrase differently, he reads it as saying “and those ritually contaminated will call out [about others] ‘Ritually contaminated!’ ”

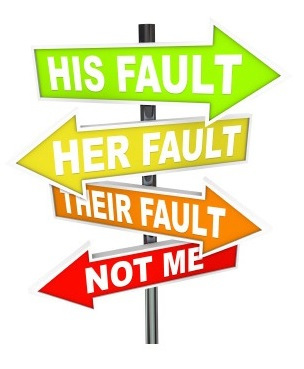

In other words, people tend to project their own deficits onto others. As the amora Shmuel said, in the context of genealogical status: “Those who assert a flaw [in others], their own flaw is what they assert” (Kiddushin 70a).

Indeed, it isn’t uncommon to see people in the public sphere who seem to make a habit of accusing others of a particular proclivity or wrongdoing being exposed as having the same proclivity or having been engaged in the same sin.

And in the private sphere, if we ever have the unpleasant experience of being accused of something by someone who is given to lobbing the same accusation at others, we might do well to pause. And, rather than take the allegation personally, realize that the accuser may, in fact, simply suffer from insecurity, and is really accusing himself.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran