Some people, like pollster James Zogby, see Israeli offerings of hummus and babaganoush as a form of “cultural genocide.” And cookbook author Reem Kassis says that the marketing of hummus as an Israeli food makes her feel that she doesn’t exist.

Parshas Beha’aloscha – The Pain of Exquisite Empathy

Suspecting someone who isn’t deserving of suspicion is reason for punishment, says the Talmud (Shabbos, 97a), citing the account at the end of the parsha, where Aharon and Miriam speak negatively about their brother, Moshe Rabbeinu.

Interestingly, though, the text of the Torah only relates Miriam’s punishment, her affliction with the skin disease tzara’as, and not Aharon’s:

“The cloud had departed from atop the Tent and behold, Miriam had tzara’as [white] as snow. Aharon turned to Miriam and behold, she had tzara’as” [Bamidbar 12:10].

While Rabi Akiva (in the Gemara cited above) asserts that Aharon, too, was afflicted with tzara’as, Rabi Yehudah ben Beseira disagrees. But he offers no reason for why Aharon, who also was part of the misdeed, would have been spared punishment.

What occurs is that Aharon was indeed punished, though not with his own tzara’as. His punishment was seeing his sister afflicted. Read the quote from the Torah above again. Is there a reason why we need to be told that Aharon “turned to Miriam” and saw her disease?

Perhaps there is indeed, because that was Aharon’s punishment. He was the exemplar of kindness, the “lover of peace and pursuer of peace (Avos, 1:12),” a man who was pained by strife, a man of exquisite empathy.

Thus, Miriam’s pain and shame, when Aharon witnessed it, became his pain and shame.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Parshas Naso – An Opportunity, Not an Ordeal

I cringe when I read someone’s portrayal of the law of Sotah ritual as some sort of “trial by ordeal.”

That phrase conjures images like the 17th century Salem witch trials, when Puritans invoked “tests” to determine whether someone was a witch. The accused was subjected to an often life-threatening experience, and only perishing as a result of the ordeal would yield an innocent verdict. When a suspect survived being bound and thrown into deep water, she would be subsequently executed. And if she drowned (the more common result), the innocent verdict was of little use to the exonerated.

By contrast, the Sotah law kicks in — or kicked in, until the Churban Bayis Rishon (and, according to one opinion in the Talmud was never used) — when a man suspects his wife of being unfaithful, warns her to not seclude herself with a particular other man, and she ignores the warning. The ritual has her drinking a concoction consisting of water, a bit of dirt from under the Temple’s marble floor, a bitter herb and the rubbed-off dried ink of the text of the Torah’s description of the Sotah ritual, including Hashem’s name.

If the woman is guilty of betraying her marriage, the Torah explains, she and the man with whom she sinned will, upon her drinking the concoction, suffer a terrible death. If she’s innocent, she will suffer no ill effects and, on the contrary, will be blessed with healthy children.

The Sotah-drink ingredients are, if unappetizing, innocuous. And so, it would take a divine intervention to bring about the punishment.

Interestingly, though, and tellingly, if the wife chooses to simply dissolve her marriage and forfeit the financial support promised her at her wedding, we compel the husband to grant her a divorce, and she suffers no other penalty

So there is no “trial by ordeal” here. What there is is a way to establish an accused woman’s innocence of adultery, a means of returning love and trust to her marriage.

The entire point of the Sotah ritual, in other words, is to convince a jealous husband that his wife remained faithful to him. Which explains why, unlike in every other case of a suspected crime or sin, we involve a Divine intercession – Hashem’s own assurance that the woman is innocent.

The ritual is not intended as a way to convict, but to restore marital peace. And Hashem Himself, the “third partner” in a successful marriage (Kiddushin, 30b), has a stake here.

Which explains Rabi Yishmael’s comment (Shabbos, 116a) about the ritual: “In order to make peace between a husband and his wife, [Hashem in] the Torah says: My name that was written in sanctity shall be erased in the water.”

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Shavuos – Happy Anniversary

In contrast to Pesach’s matzos and Sukkos’ sukkos and arba minim, Shavuos is unique among the Shalosh Regalim for its lack of any positive ritual-commandment.

That may have to do with the holiday’s association with Mattan Torah.

Because that experience involved no particular action; it was, in a sense, the very essence of passivity, the acceptance of Hashem’s Torah and His will. Hashem was the actor; our ancestors’ response was to receive, to submit to the Creator.

Mattan Torah is famously compared by various Midrashim to a wedding, with Hashem the groom and His people the bride. (Many chasunah minhagim reflect that metaphor: the chuppah recalls the mountain held over the Jews’ heads; the candles, the lightning; the breaking of the glass, the shattering of the luchos.)

And just as a Jewish marriage is legally effected in the kallah’s simple choice to accept the wedding ring or other gift the groom offers, so did Klal Yisrael at Har Sinai create its eternal bond with the Creator by accepting His gift of gifts.

And so, a positive, active mitzvah for the day would arguably be in dissonance with the day’s central theme of receptivity.

Shavuos’ identification with our collective identity as a symbolic bride, moreover, may well have something to do, too, with the fact that the holiday’s hero is… a heroine: Rus, whose story not only concerns her own wholehearted acceptance of the Torah but culminates in her own marriage.

It isn’t fashionable these days to celebrate passivity or submission, even in those words’ most basic and positive senses. But Judaism, unlike fashion, is eternal.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Yetzias Kaufering

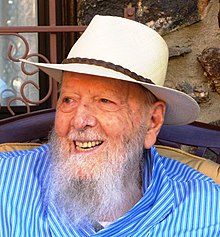

Pesach Sheni is a special day in my family, because in 1945, on that day of the Jewish calendar, my father-in-law, who passed away earlier this year, was liberated from Dachau by American soldiers.

You can read about his last days in the concentration camp, and about his family’s marking of that day each year, here.

(Photo is of my father-in-law and one of his orphan charges in France.)

The Marijuana Express

Marijuana legalization in an increasing number of states has yielded some panic and some nonchalance. Neither is really warranted, in my opinion, and you can read why I feel that way here.

Parshas Bamidbar – Desert and Direction

The sefer of Bamidbar (or, to be pedantic, B’midar) begins with the word Vayidaber; and the Talmud Yerushalmi, I’ve seen it cited, even calls the sefer by that latter word.

Both words, as it happens, share the same three-letter Hebrew root, d-v-r, even though one means “desert” and the other “speak.”

What common element of meaning could associate a desert with speech?

The answer may lie in yet another word with the exact same three-letter root, a word that means something else, seemingly, altogether. In Tehillim, we find the phrase yadber amim tachteinu (47:4), which can be translated “He will guide the nations under us.” Although Rashi and the Targum on Tehillim take a different approach to the word yadber, the Gemara (Shabbos 63a) understands the word to mean “guiding,” and the context of the pasuk supports that understanding. The Radak and Ibn Ezra also translate it that way.

Speaking (especially the sort of speech with which the word dibbur is associated: clear, strong words) guides the one spoken to in a particular direction, to hearing the meaning or directive of the speaker. So it isn’t terribly farfetched to imagine that yadber and vayidaber are subtly related.

Midbar, though, seems a puzzle.

What occurs is that a midbar is a desolate, featureless place, usually dangerous, for lack of food and water, and the presence of snakes and such. But the challenges and dangers may not be what inheres in the word midbar; certainly, the desert through which the Jews were wandering lacked those threats; the well of Miriam, the maan and the cloud of protection made it a safe place.

But it remained one without distractions, and was the path, if a convoluted one, leading the people, guiding them, to their goal, Eretz Yisrael.

Might the word midbar’s essential meaning reflect not desolation nor danger, but the idea of an open path leading to a goal beyond it, toward which one is being guided?

And, even in our own lives, might obscuring the distractions around and within us help us perceive where we are supposed to go?

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Two Paths to the Happy End of History

Between the lines of the terrible description in parshas Bechukosai of what will happen if Klal Yisrael abandons the mitzvos of Hashem lie subtle hints to the limits and end of those curses. The land will not yield produce (making it inhospitable to occupiers); there will be years of barrenness (but as an atonement for the unobserved shemitos); we will be scattered throughout the world (making it impossible for our enemies to isolate and destroy us – Rabbeinu Bachya).

And, of course, after the long, painful recounting of the tragedies that might befall us, Hashem offers the assurance that “But despite all this, while they will be in the land of their enemies, I will not have been revolted by them, nor will I have rejected them or obliterated therm, to annul My covenant with them” (Vayikra 26:44). And that He “will remember My covenant with Yaakov and also My covenant with Yitzchak, and also my covenant with Avraham…” (26:42).

So even within the curses are blessings; and when the evil passes, what will remain will be Hashem’s covenant with our forefathers, and our salvation as a people through its merit.

So what the Torah is saying is that there will be a happy end to history but that there are two ways it can be reached: We can choose good and get there in a direct fashion; or, chalilah, we can choose the opposite and have to endure a long, grueling and tragic galus-journey… but to the same destination. Our forefathers’ merit ensures that all will, in the end, be well.

In other words, our suffering, should our choices make it necessary, will also have become part of Hashem’s plan.

An idea subtly echoed in the final law of the parshah, temurah.

It is a sin to attempt to transfer the holiness of a consecrated animal to another one. And yet, the sin nevertheless effects holiness, as the second animal becomes holy as well.

Even our sins, for which we are responsible, can all the same end up yielding the fruition of Hashem’s plan.

Hu us’muraso yih’yeh kodesh. (ibid 27:10.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Two Jews Walk Into a Palm Springs Shul

A piece I wrote for Forward about my late father-in-law’s friendship with the celebrated novelist Herman Wouk — whose second yahrtzeit was last Shabbos — can be read here.

Parshas Emor – Embracing Our Worlds

A strange and strangely familiar phrase is found in Rashi, commenting on the Torah’s introduction of the account of the mekalel, the blasphemer, with “And he went out” (Vayikra, 24:10)

Rashi, quoting Rabi Levi in a Midrash, elaborates: “He went out of his world.” The idea of an individual’s personal “world” is also employed by the renowned 18th century Italian mystic Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzato in the very first sentence of his famous work Mesilas Yesharim. He introduces his book by stating that the essence and root of human service to the Divine begins with a person’s effort to clarify and establish “what his obligation is in his world.”

That each of us has his or her own world is a curious notion. I think it means that each of us has a unique spiritual essence that needs to be expressed in a unique way and utilized in service to Hashem. Intriguingly, that idea resonates powerfully with the second Midrash Rashi cites about the phrase “And he went out” — that the blasphemer has just left the court of Moshe, where he had lost his case.

That case involved his claim, since his mother was Jewish (although his father was an Egyptian) that he was entitled to a portion of land in the area of his mother’s tribe, Dan. The ruling, however, was that, while he was a member of the Jewish people, he — uniquely, among the people — owned no portion of the land.

That left him with two options: Either to accept that fate, and recognize that it was “his world” – a personal situation that somehow positioned him for a particular, singular role to play in society. Or to reject the ruling angrily. He chose the second path, and then some. Thus he “left” not only the court but his world.

Some people who see their life circumstances as “unfair” face a similar choice. The key to true success in life — which, of course, is unrelated to profession, wealth, fame or pleasure — is seizing one’s individual, unique circumstance, no matter how limiting or painful or puzzling it may be, recognizing that it is his or her “own world” –what makes them special. And then, after ascertaining what that specialness seems to demand, getting down to work.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran