The Catholic Church as an institution has come a long way with regard to its attitude toward the Jewish people. But, apparently, it still has, as they say, a ways to go.

You can read what I mean here:

The Catholic Church as an institution has come a long way with regard to its attitude toward the Jewish people. But, apparently, it still has, as they say, a ways to go.

You can read what I mean here:

“Why display yourselves when you are satiated, before the children of Esav and Yishmael?” (Rashi, Beraishis 42:1).

That is the Gemara’s (Taanis 10b) understanding of Yaakov Avinu’s exhortation to his sons, lama tisra’u (understood, apparently, as “why be conspicuous?”). His rhetorical question was posed to ensure that “they will [the children of Esav and Yishmael] will not be jealous of you….” as they journey to Mitzrayim to garner food during the famine.

Chazal say that, in general, “a person should not indulge in luxury” [ibid]. But especially when it might generate jealousy and resultant animosity.

It is a lesson for the ages, and needed throughout the ages. Among others, the Kli Yakar, who died in 1619, lamented the fact that some Jews’ homes and possessions in his time proclaimed their material success. The problem has hardly disappeared today.

(One of the things that attracted me to the community where I live was the basic uniformity of the homes there. There are no mansions here, not even McMansions.)

Several commentaries wonder at the Gemara’s reference, in the opening quote above, to the progeny of Esav and Yishmael. Yaakov was in Cna’an. Wouldn’t it have made more sense for Chazal to make their point about not standing out with regard to Yaakov’s neighbors, the Cna’anim? There’s no reason to believe that Esav and Yishmael’s people were nearby.

What occurs to me is that there is a poignant prescience in Chazal’s comment. They may have sensed, or even foreseen, a distant but long-running future of Klal Yisrael, where so many of its members would be residing, as has been the case for many centuries, amid cultures associated with Esav and Yishmael.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

It wasn’t very long ago that the idea of government funds helping parents who choose private religious schools for their children was anathema. That’s blessedly no longer the case. To read about what may lie on the horizon, please click here.

The nature of the “work” that Yosef came to Potifar’s house to do on the day when the Egyptian’s wife sought to entice him to sin with her (Beraishis 39:11) is famously the subject of a disagreement between Rav and Shmuel.

One opinion is that Yosef intended “to do his [household] duties”; and the other, “to do his needs,” i.e. to submit to the woman’s blandishments – an intention that was undermined only after an image of Yaakov appeared to Yosef, giving him the strength to resist (Sotah 36b). (That latter opinion, with its portrayal of Yosef as vacillating before finally resisting may be audibly symbolized by the shalsheles cantillation of the word vayima’en, “and he resisted.”)

Rav Simcha Bunim of Pshischa is quoted to have commented that the word “work” employed at the pivotal point in Yosef’s life – when he earned the appellation tzaddik, “righteous” – holds the message that each of us has a “work” to accomplish in his life, not just in a general sense but with regard to acting – or not acting – at a pivotal moment, when we are faced with a decision that will define us.

Yosef’s life-changing moment was when he was faced with an insistent Mrs. Potifar. Every person, the Pshischer suggested, will be faced with a pivotal moment, or moments, of his own, when his choice will make all the difference.

Which idea may lie behind Targum Onkelos’ translation of “his work.” He renders it in Aramaic as: “to audit his [Potifar’s] financial records.”

While that may simply be a presaging of the time-honored Jewish profession of accounting, the word Onkelos uses for “his financial records” is chushbenei. The word’s root is cheshbon, “accounting,” and it brings to mind its use in the phrase cheshbon hanefesh – an accounting of one’s “soul,” an examination of one’s standing in his spiritual life.

Each of us is charged with discerning moments in life, when the choice before us may be pivotal. Of course, we never know whether what we are facing is indeed such a moment. And so, we are wise to treat every decision we face as potentially momentous.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

On a recent Friday night, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) held its “30th anniversary gala” in Washington, DC. Too bad you probably missed it.

Something the celebrants didn’t know was that some bad news (at least for them) lay on the horizon. To read what it was, please click here.

Imagine finding yourself in a desolate place and spying a lone figure in the distance coming toward you. Your apprehension, even nervousness, would be understandable. But then, when he comes closer and you see that it’s a man with a long white beard, wearing a hat, kapoteh and tallis, you’d breathe a sigh of relief. Until he suddenly attacks you, gets you in a headlock and bends your arm painfully behind your back.

The angel that confronted Yaakov when our forefather re-crossed Nachal Yabok to retrieve some small items looked, according to one opinion, “like a talmid chacham” [Chullin 91a].

The most straightforward takeaway from that contention is that one cannot rely on the appearance of a person as being reflective of his essence. That’s an important lesson, as it happens, for all of us, and to be imparted to our young. Honoring someone who looks honorable is fine, but trusting him requires more than that.

But there’s a broader, historical message in that image of a faux talmid chacham too.

From the 19th century Wissenschaft des Judentums movement to the Reform and Conservative ones to the Jewish nationalism that sought to replace Torah with a Jewish state to “Open Orthodoxy,” there have been many efforts to distort the essence of Judaism – dedication to the Creator and His laws for us.

They have all sought to don conceptual garb proclaiming their “Jewish” bona fides. But they have all been revealed to be no less masqueraders than the sar of Esav wrapped in a tallis.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

With all the wacky wokey warriors spewing hatred for Israel and Jews on college campuses and city streets, one could be forgiven for not noticing the proliferation of anti-Semites on the other end of the political spectrum.

But they’re there, and, in a way, more threatening. You can read about some of them here.

A piece I wrote about the future of school choice is here.

Yaakov and Leah had their first (perhaps only) argument on the morning after the wedding feast. He had expected Rachel to join him in his abode that night but, unknown to him until morning’s light, “behold, it was Leah” (Beraishis 29:25).

Midrash Rabbah (ibid) recounts how our forefather exclaimed “Deceiver, daughter of deceiver! Did I not call out ‘Rachel’ and you answered me?”

Leah well parried the thrust: “Is there a barber without apprentices? Did your father not call out ‘Esav’ and you answered?”

Touché.

But the Torah isn’t a drama presentation. And the Torah doesn’t criticize either subterfuge. What are we to glean about our lives from that comeback? On the most simple level, I think it conveys something about how we – whether we are teachers, parents or just people (because all of us are examples to those around us) – convey less (if anything) with words than we do with our actions.

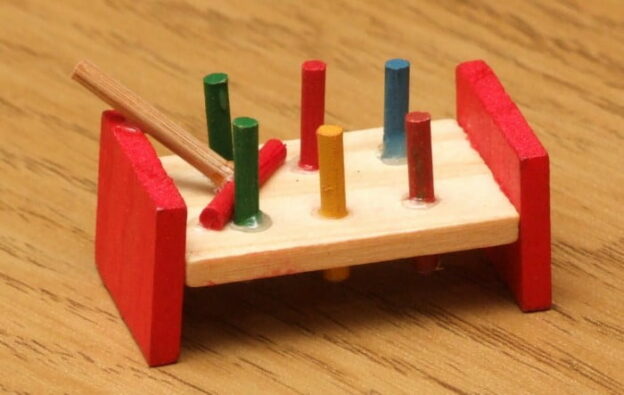

I learned that lesson well, if a bit embarrassingly, many years ago, when I was typing away on a keyboard and my four-year-old son sat down on the floor near my desk with a pegs-and-holes toy, which his imagination had apparently repurposed into a word processor (this was B.C. – Before Computers), and proceeded to imitate me.

It was very cute, and I smiled. Until, that is, his little sister crawled over and tugged at him. Showing annoyance, he turned to her and said, loudly and tersely, “Will you please stop? Can’t you see I’m working?” Yes, he was, as they say in the theater, inhabiting his character.

One of the answers to the Chanukah question of why the cohanim needed to find a sealed flask of oil despite the fact that tum’a hutra b’tzibbur – ritually defiled entities are permitted in many cases for public use – is attributed to the Kotzker Rebbe. He explained that that principle does not apply when a crucial, new era is being initiated, which was the case when the Chashmonaim rededicated the Bais Hamikdash. At so important a time, purity cannot be compromised.

The term for “initiation” is chinuch. And it is also used to mean “education.” When we educate others, especially the young, we do well to ensure that our actions are pure.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Nations’ annexation of territory, although it tends to cause much clutching of pearls, is not rare.

But the proposed-in-some-circles annexation of Yehudah and Shomron (the “West Bank”) raises an issue that needs to be carefully thought through.

To read what, click here.