As you may know, there was massive fraud in the 2020 presidential election. And birds are not the innocent animals they seem to be, as you can read here.

As you may know, there was massive fraud in the 2020 presidential election. And birds are not the innocent animals they seem to be, as you can read here.

It is interesting that the concept of hakaras hatov, “recognition of the good” that one has experienced, appears not only in the parsha, at the beginning of the Sefer Shemos saga whose apogee is the creation of Klal Yisrael, but also at the beginning of human history itself.

It is Aharon, not Moshe, who initiates the makkos that require the Nile to be hit (Rashi, Shemos 7:19), because the river sheltered Moshe when he was a baby. Likewise when, at the makka of kinim, the ground needed to be hit, it was Aharon who did the act, not Moshe, since the ground had helped Moshe hide the body of the Egyptian taskmaster he killed in Mitzrayim (Rashi, Shemos 8:12).

And, back at the beginning of the Torah, it was necessary that the first man be created in order for the already-created vegetation to sprout from the ground, since, until Adam’s arrival, “there was no one to ‘recognize the good’ of rain and pray for it (Rashi, Beraishis, 2:5).

Hashem, of course, didn’t need Adam to bring rain. And Hashem could have had all the makos come about without any hitting of anything. But He chose to have the Nile and the ground be intermediaries of His will – to stress, as per the Midrashim Rashi cites, as above, the critical importance of hakaras hatov. Clearly, it’s a concept fundamental to the evolution of humanity, stressed at the beginning of history and the beginning of Klal Yisrael.

And while hakaras hatov may be expressed in an action or toward an object, it is always, ultimately, a recognition of the ultimate source of good, Hashem.

Which is why Jewish days begin with Modeh ani and end with Hamapil, and why they are filled with the recitation of birchos hanehenin and birchos hoda’ah.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Noted historian Deborah Lipstadt was nominated by President Biden to head the administration’s Office to Monitor and Combat Anti-Semitism. She should be a shoo-in but her appointment has been stalled. To read why, click here.

I’m not in the habit of writing non-Jewish holiday-season pieces but did so recently. My essay appeared in the Washington Post but can be read paywall-free here.

My rebbe, Rav Yaakov Weinberg, zt”l, often spoke of how each of the Jewish forefathers was challenged by Hashem to act in opposition to the very characteristic that defined him.

Avraham, whose middah is chessed, kindness (evident, for example, in his rejoicing at being able to entertain guests even when he was in physical distress, and in his defense of S’dom), has to part ways with his nephew Lot, essentially sending him away (though kindness peeks through even then, when the decision of which direction to take is offered Lot). Then he has to banish Hagar and Yishmael from his home. War being the antithesis of kindness, he needs to fight (although, with chessed again evident, as he was fighting to rescue Lot) in the War of the Kings. Following Hashem’s commandment to circumcise himself and the males in his household, moreover, alienated people he wanted to bring close to Hashem (Bereishis Rabbah 47:10).

Yitzchak’s middah is din, strict judgment. And his judgment of which of his sons deserved the brachos was frustrated by Yaakov. Yitzchak was forced to acknowledge that his judgment had been wrong.

Yaakov, whose middah is emes, truth, had to pretend, guided by Hashem through Rivka, that he was his brother; and then, again directed by Hashem, enters an agreement with his father-in-law Lavan to deprive him of much of his flocks. And Yaakov steals away with his wives without telling Lavan straightforwardly that they are leaving.

In our parshah, we meet Moshe, who dominates the rest of the Torah’s narrative portions (and whom the Torah is “named” after: Toras Moshe). What we know about his character is that he was a “very humble man, more so than any other man on earth (Bamidbar 12:3).”

And, against his will, he is called on by Hashem to lead Klal Yisrael. He has a speech defect and yet must be Hashem’s spokesman. He tries to have his brother Aharon take the reins, but Hashem insists that he lead, and he does.

In life, we are sometimes called to act against our natural grain. And our first reaction is often, “No, that’s just not me.” But we do well to stop and consider that maybe filling a role that doesn’t seem to fit our essential disposition may be precisely what Hashem wants from us, and may hold the potential of great merit.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

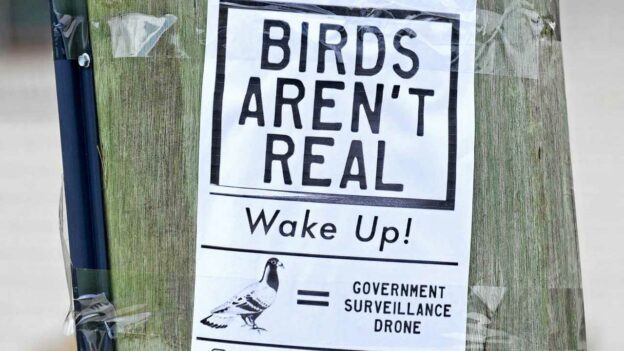

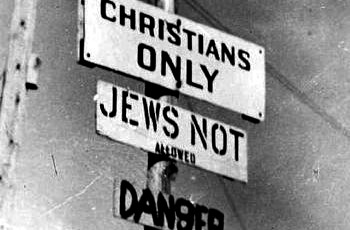

It may have started back in the summer of 2020, when a Kansas Republican county chairman posted a caricature of the state’s Democratic governor Laura Kelly on his newspaper’s Facebook page. Ms. Kelly had issued a public-setting mask mandate, and was depicted wearing a mask with a Magen David on it. In the background was a photograph of European Jews being loaded onto train cars. The caption: “Lockdown Laura says: Put on your mask … and step on to the cattle car.”

The next summer, we were treated to Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene’s criticism of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s mask requirement for the chamber, in which Ms. Taylor Greene declared: “You know, we can look back at a time in history where people were told to wear a gold star… were put in trains and taken to gas chambers in Nazi Germany. And this is exactly the type of abuse that Nancy Pelosi is talking about.” Under pressure from her peers, the congresswoman later apologized; but her point, such as it was, had been made, and likely energized her like-minded supporters.

Then came Oklahoma GOP chairman John Bennett’s comparison of private companies requiring employees to get vaccines to — three guesses — the Nazis’ forcing Jews to wear a yellow star.

The odious comparisons just seemed to pile up, across the country. They were getting attention, after all, and attention is catnip for political felines. Of course, the offensive comments, each in turn, were all roundly condemned by Jewish groups. Wash, rinse and repeat.

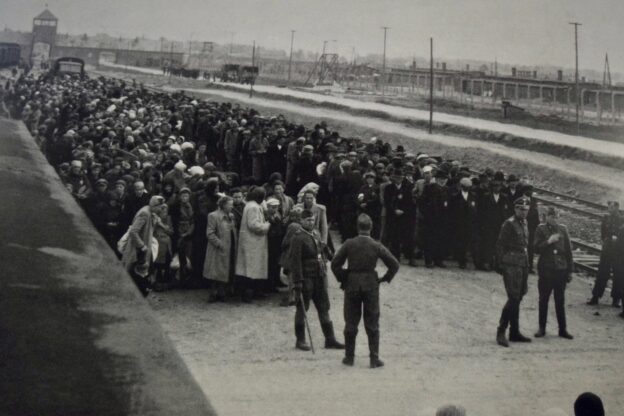

Last week, though, may have offered us the Mother Of All Such Slurs, when broadcaster Lara Logan, once a respected CBS News foreign correspondent and now a Fox Nation commentator, appeared on the “Fox News Primetime” program, where she addressed Dr. Anthony Fauci’s recommendation that Americans get fully vaccinated, including booster shots, in the wake of the appearance of the Omicron COVID variant. Her words:

“This is what people say to me, that he doesn’t represent science to them. He represents Joseph Mengele, the Nazi doctor who did experiments on Jews during the Second World War and in the concentration camps. And I am talking about people all across the world are saying this.”

A cursory search turns up no one but Ms. Logan saying such a thing, but maybe those people all across the world spoke with her privately.

As usual, Jewish groups rightly rushed to condemn her statement. But she was impervious to the criticism, later re-tweeting to her 197,000 Twitter followers a Jewish fan’s comment: “Shame on the Auschwitz Museum for shaming Lara Logan for sharing that Jews like me believe Fauci is a modern day Mengele.” Well, that makes two people, anyway.

This introduction shouldn’t be, and probably isn’t, necessary, but for any readers not fully familiar with Josef Mengele, yimach shemo vizichro: He was a Nazi doctor given the title “Todesengel” — German for malach hamaves. At Auschwitz, he performed deadly experiments on prisoners, selected victims to be killed in the gas chambers and helped administer the Zyklon B, or hydrogen cyanide, gas.

Mengele was particularly interested in twins, separating them on their arrival at the concentration camp, and performing experiments on them, including infecting them with germs to give them life-threatening diseases, performing operations on them without anesthetics and killing many of them to compare their and their siblings’ internal organs.

As to Dr. Fauci’s sin, it is being cautious — overly so, to his critics — about public health measures.

Aside from the insult and offensiveness of the Holocaust comparisons, the repeated use of the murder of six million Jews as a political tool should bother us for another reason:

With each one, even dutifully followed by condemnations, the memory of Churban Europa is further dulled a bit, the force of its historical reality subtly blunted. The public mind is, slur by slur, lulled into regarding the Holocaust as a mere metaphor. That may be of no concern to the offenders, but it should be to us.

Because the cascade of casual co-optings of the Holocaust to score political points dovetails grievously with the diminishing number of living links to the events of 1939-1945.

And all the loathsome little Holocaust deniers and revisionists are just licking their lips as they wait in the wings.

© 2021 Ami Magazine

Chesed v’emes, “kindness and truth,” is the term Yaakov Avinu uses to describe what he is asking of Yosef when charging his son to not bury him in Mitzrayim (Beraishis 47:29).

And Rashi famously explains that the term is meant to reflect the fact that doing something for someone deceased is the ultimate kindness – since the doer “isn’t looking toward repayment,” presumably from the recipient of the act.

But while the deceased is no longer in a position to repay the kindness, others certainly are. And the performer of the kindness can also expect reward of a greater sort – in the world-to-come. So why is doing chesed for a deceased person in a singular category?

I wonder if the answer might lie in the words “isn’t looking for” (eino metzapeh) in Rashi’s explanation (although I haven’t found those words in the Midrash that Rashi seems to be citing).

What Rashi might mean is that, while there may indeed be repayment for an act of kindness toward someone no longer able to reciprocate, the performer of the kindness isn’t looking toward repayment. Because he’s in a special state of mind, bluntly confronting the inevitability of death. When he performs his kindness, he is blinded to everything but his own mortality.

Facing head-on what we all too often choose not to think about, although we intellectually know it is real, puts screeching brakes on our merry marches toward success in life and achievement of rewards of all sorts. At that time, we do not look toward any compensation for our efforts.

Interestingly, the word “eivel”, “mourning,” is spelled precisely as the word aval, “however.” What “however” does in a sentence – interrupts and reverses its flow – is what death of a loved one does in a survivor’s life. It stops the speeding “reward pursuant” train and focuses the mourner exclusively on the inevitable truth that this world is ours only until it isn’t.

And so, a chesed done for someone deceased is done in a singular state of pureness, of emes.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

My Ami column last week, about two recent much-publicized trials, can be read here.

The wagons (agalos) that Yosef sent back with his brothers to their father (Beraishis 45:27) were intended to convince Yaakov it was indeed Yosef who was the effective ruler of Mitzrayim. They were, as Rashi there explains, a pun-hint to what Yosef and Yaakov were speaking of when they last saw one another, 22 years earlier.

The subject of that discussion was the law of “egla arufah,” the ritual performed when a person is discovered murdered outside a city. Yaakov had, back then, accompanied Yosef as he went looking for his brothers, and explained that the law of egla arufah implies the importance of escorting someone who is going on a journey.

The agalos were meant to conjure egla, which means “calf,” as the ritual involves dispatching one.

Why, though, use a pun? Why didn’t Yosef simply send a calf to his father? Wouldn’t that have been a more effective means of identifying himself?

There may, though, have been a deeper message in the agalos. The root of the word is “wheel.” It might thus imply, for lack of a better phrase, the closing of the circle of justice, as we colloquially say, “what goes around comes around.” The circle is the most perfect simple shape, and can be seen as representing the resolution of all that seems discordant or incomprehensible.

As the ancient proverb has it: “The millstones of G-d grind slowly but exceedingly fine.” And millstones, of course, are round.

When Hillel saw a skull floating in a river, he said :” Because you drowned others, they drowned you. And in the end, those who drowned you will be drowned” (Avos 2:6). Obviously, not every drowned person had drowned someone else. Hillel’s statement is a conceptual declaration, namely, that ultimate justice is assured. And perhaps significance lies in the fact that what he spied was a skull, a gulgoles, literally “something round.”

So Yosef’s message to his father in the identifying hint he sent, may have been: “All has turned out fine, despite my travails; my brothers and I are reconciled, and not only has the family circle not been broken, our lives have come… full circle.”

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

To the Editor:

Judaism permits, even requires, abortion in limited cases, and responsible Jews cannot endorse measures that give a fetus the same protections as a born child.

But, with regard to Sarah Seltzer’s rumination on Judaism’s abortion position, there is nothing whatsoever in the Jewish religious tradition that permits abortion as a mere “choice” to be made for personal, economic or social reasons.

Nothing whatsoever.

(Rabbi) Avi Shafran

New York

The writer is director of public affairs at Agudath Israel of America.