Also, an essay I wrote for Religion News Service about the stalled Deborah Lipstadt nomination can be read here:

Also, an essay I wrote for Religion News Service about the stalled Deborah Lipstadt nomination can be read here:

The Polish envoy entrusted several months ago with the mission of improving relations with Jews recently called his country’s 2018 law criminalizing claims that Poles were complicit in the Holocaust “one of the stupidest” laws ever. To read why, and the end of the story, click here.

What an abrupt transition, from the miracles and wonders of the earlier parshios of Sefer Shemos to this week’s list of prosaic, painstaking laws.

But, just as every letter in the Torah is necessary for it to be kosher, so are life’s seeming banal interactions, in reality, opportunities for holiness. When we conduct our personal and business lives properly, not as rote or out of a self-generated sense of right or wrong but in fulfillment of Hashem’s commands, that is no different from the mitzvos that recall kri’as Yam Suf.

Anshei kodesh, “people of holiness” (Shemos 22:30), is our divine prescription. The Kotzker Rebbe is said to have remarked that “Hashem has more than enough angels; He wants people of holiness.” He wants our humdrum human lives to be infused with holiness.

A corollary of that thought lies in the realm of Hashem’s hashgacha, which covers our every experience. Not only when it’s readily evident, in seemingly “miraculous” happenings, but no less in our “mundane” lives.

A friend of one of our daughters once shared a powerful story with her, about a woman scheduled to fly to a distant city for an important job interview. The lady found herself stuck in unexpected traffic and arrived at the airport in barely enough time to park her car. She ran to the check-in counter, only to discover that she had missed her flight by mere seconds, and that there were no others that would get her to her interview on time. Dejected, she headed home.

Several hours later, the plane on which she was to have flown began its descent to its destination, the woman’s reserved seat empty… As the plane descended, there was some turbulence, and the captain told the passengers to make sure their seat belts were securely fastened…

And then, the plane… touched down, safely. The passengers disembarked. End of story.

The lady never discovered any reason for having lost the chance of the job, and ended up taking a less lucrative one in her home city.

But there was a reason.

Whether we perceive it or not, there always is.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran

“Is anyone there? Can you hear me?” You shout at the rubble of a collapsed building. No reply, but then… was that tapping?

You have an idea. “If you can understand me,” you yell, “tap once.” A single tap. “If you’re injured,” you then say, “tap twice.” Two taps. There’s someone there.

An apt metaphor for something very important. To read what, please click here.

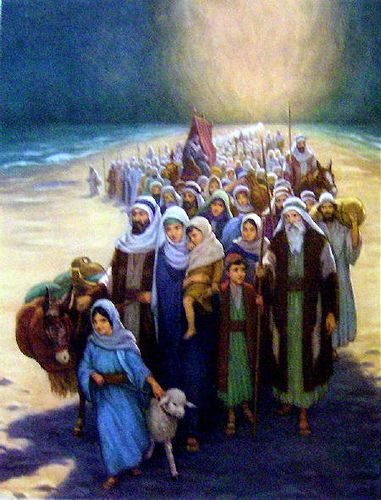

Last week, I offered the idea, based on the three Hebrew words, shiluach, yetziah and geirush, used to describe both the exodus account and a marriage’s dissolution, of Yetzias Mitzrayim as Klal Yisrael’s “divorce” from Egypt and Har Sinai, as its subsequent “betrothal” to Hashem.

The latter image, in fact, is clear from the Midrash Rabbah (Acharei Mos 20:10), which comments on the words “the day of his marriage” in Shir HaShirim (3:11): This, comments the Midrash, is Har Sinai.

And from the Mechilta D’Rabi Yishmael on Yisro, which quotes Rabi Yehuda as explaining that “Hashem from Sinai came” (Devarim 33:2) conveys the image of “a groom going out to receive his bride.”

The chuppah at a Jewish wedding recalls (“bisachtis hahar,” Shemos 19:17) the mountain lifted over the head of the people at Sinai; the candles borne by parents, the lightning; the groom walking forward to greet his bride, the aforementioned Mechilta.

And the end of the birchas eirusin at a Jewish wedding refers to Hashem as having “sanctified His people Israel through chuppah and kiddushin.” Not “with the mitzvos of chuppah and kiddushin, but through those things themselves – namely, at Sinai.

But the mountain above the people is also understood by Chazal as a threat. Rav Avdimi bar Chama bar Chasa says that “Hashem overturned the mountain above the Jews like a barrel and said to them: ‘If you accept the Torah, good; but if not, there will be your burial’” (Shabbos 88a).

Although that intimidation was mitigated later in history, when, in the time of Esther and Mordechai, the people re-accepted the Torah entirely willingly [ibid], what is the significance of the coercion in the first place?

The answer may lie in Devarim 22: 28-29, where the law is set down in the case of a man who forces himself upon a young woman. He is fined the sum of fifty silver coins but also must (if the woman wishes) marry her and, unlike in any other marriage, cannot ever divorce her.

The implication for Hashem’s relationship with Klal Yisrael should be self-evident.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran

What does the James Webb Space Telescope have to do with a quote of Albert Einstein in a letter from Rav Mordechai Gifter? Glad you asked. You can read the answer in my most recent Ami column, available here: https://www.amimagazine.org/2022/01/05/behold-the-eyes-of-webb/

The push to balkanize the Kotel Maaravi is, as its proponents readily admit, intended as a step toward legitimizing American-style “Jewish religious pluralism” in Israel. That would be a disaster, not only because of the notion’s inherent falsehood — that there are different “Judaisms” — but demographically too, since non-halachic “conversions,” “divorces” and the like have wreaked havoc on the unity of American Jewry.

What is more, the Kotel has always served as a unifier of Jews, whatever their backgrounds or beliefs — probably the only place on earth where so many different kinds of Jews pray side by side.

If you wish to register your chagrin at the plan to partition the Kotel, you can do so easily by visiting:

There is no charge for doing so, and, by sending the letter (or one of your own crafting), you can help show that a good part of “American Jewry” wants the status quo at the Kosel to be retained.

Tizku limitzvos.

Shalach, the root of the word of the parshah’s title, is used elsewhere regarding the exodus from Mitzrayim (e.g. shalach es ami). So are the words yetziah (e.g. Shemos, 20:2) and geirush (e.g. ibid 11:1)

Intriguingly, each of those characterizations of our ancestors’ march from Egypt is also associated with… divorce. Vishilcha mibeiso (Devarim 24:2); viyatz’ah mibeiso (Devarim 24:1); isha gerushah(Vayikra 21:7).

The metaphor telegraphed by that fact is clear. Klal Yisrael was virtually “married” to Mitzrayim, sunken to near its deepest level of tum’ah, and, with Hashem’s help, freed from that “marriage,” divorced, as it were, from Mitzrayim.

The symbolism doesn’t stop there. When the divorce is finalized, Klal Yisrael gets re-married, this time, permanently, to Hashem, with Har Sinai over the people’s heads serving as a chupah. (Indeed, several marriage customs are associated by various sources with Mattan Torah – the chupah, the candles, reminiscent of the lightning), even the breaking of a glass, recalling the sheviras haluchos).

And that would dovetail strikingly with the prohibition against returning to live in Egypt (Devarim 17:16). Because a remarried woman, too, is prohibited from returning to her first husband (Devarim 24:4).

Even more interesting is the implication of the metaphor to the baffling Gemara in Sotah (2a) that asserts that a man’s “initial mate” is divinely decreed before his birth; and his second one, in accord with his behavior.

Because, in our metaphor, Klal Yisrael’s first “mate,” Egypt, was in fact decreed, to Avraham at the bris bein habisarim; and its final one, Hashem, was earned by the people’s behavior: their willingness to follow Moshe into the desert and declaration of naaseh vinishma at Sinai.

And a coup de grâce lies in how the Gemara paraphrased above describes the challenge of finding the proper mates: kasheh k’krias Yam Suf – “as difficult as the splitting of the Sea.”

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Just when it seemed the news stream couldn’t get nuttier, we were graced with the lovely story, first reported by The Washington Post, of third-graders at a Washington, DC, elementary school allegedly told to reenact horrific Holocaust scenes. To read more about that “creative” assignment, click here,

When the Torah (Shemos, 12:26) recounts the question the Haggadah attributes to the “wicked son,” it states that, when our ancestors heard it, they responded by bowing down in thanksgiving. What were they thankful for?

The Sheim MiShmuel, quoted in Eliyhu Ki Tov’s Haggadah, explains that the very fact that the Torah considers the ben rasha to be part of Klal Yisroel, someone who merits a response, was the reason for the Jews’ happiness.

When, in other words, we were a mere extended family of individuals, each member stood or fell on his own merits. And many individuals, sadly, did not merit to leave Mitzrayim.

After Yetzias Mitzrayim, however, even a “wicked son” is considered a full member of the Jewish People. The revelation of that truth demonstrated to our ancestors that something had radically changed since their pre-Egypt and Egypt days. The descendants of Yaakov had become something new, a nation.

In the Haggadah, we are told, regarding the “wicked son,” hakhei es shinav,” usually translated as “set his teeth on edge.” He has, we are told, been kofar ba’ikar, denied something essential (literally, “rejected a root”). Had he been in ancient Egypt, we tell him, he would not have been among those saved by Hashem.

A cognate of hakhei, however, exists in the Gemara (Kesuvos 61a), which notes that foods that have kiyuha, an enticing sharpness of smell, must be offered to the waiter serving them.

Might the Haggadah’s hakhei carry a similar meaning? That we are meant to entice the wicked son to join us, by telling him that had he been there – in ancient Egypt – he would not have escaped. But he is now here, post-Yetzias Mitzrayim, and thus part of Klal Yisrael, willy-nilly.

And the “something essential” that he seems, by his question, to deny may refer not to some theological “root,” but rather to his own root, planted deeply, whether he realizes it or not, within our people.

And so our response may hold our hope that his hearing and comprehending that fact will bring him to accept his status as a Jew, and to change his ways.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran