When we think of the word na’aseh, “we will do,” it is usually in the context of the phrase na’aseh vinish’ma, “we will do and we will hear” – Klal Yisrael’s statement of commitment to following the Torah’s laws, whether they are understood by reason or not.

But the word naaseh appears in this week’s (and last week’s) parsha as an independent statement, without vinish’ma following it.

And it appears as well in the Torah’s very first parsha, Bereishis, where it is Hashem Himself using it in the sense of “Let us make,” with the words “man in Our image” following.

Intriguingly, in both places – the creation of man and the revelation at Har Sinai – we find the Gemara describing angels’ opposition. In the first case, we are told of Hashem’s asking an angelic entourage if man should be created. They say no and Hashem destroys them. A second group offers the same response as the first and it, too, is destroyed. A third one, noting its predecessors’ fate, says: “The universe is Yours. Do with it as You wish.” (Sanhedrin 38b)

At Sinai, similarly, we find angels opposing the offering of the Torah to human beings. Hashem asks Moshe to respond to them and he argues that the Torah’s laws presuppose human inclinations. “Do you have a father and mother?” to honor, he asks, among other examples. “Have you jealousy and an evil inclination?” (Shabbos 89a). Only humans, in other words, can say “We will do.”

In both cases, the angels’ case seems predicated on the inherent fallibility of human beings, the likelihood that they will sin and are unworthy of existence or being gifted with the Torah.

And sin and rebellion indeed ensued, right after Adam’s creation and after the Torah was accepted by his distant descendants. So, in a sense, the angels were right. But they were wrong.

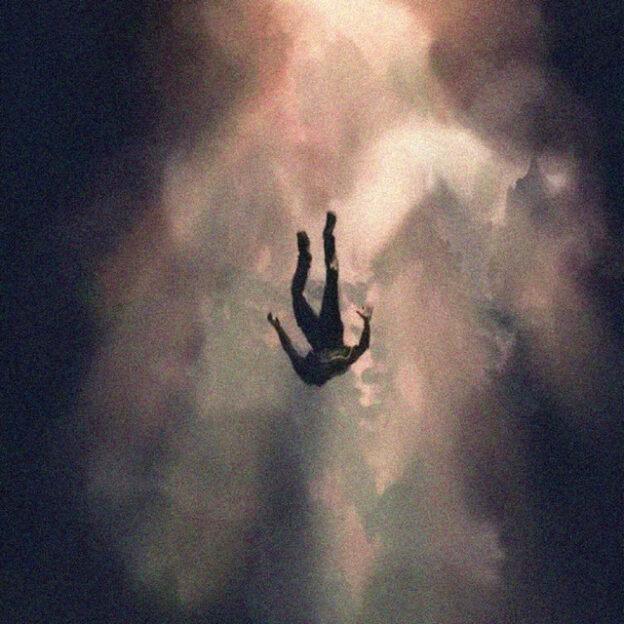

There can be no true win without the possibility of loss. No advancement without the potential for decline. No accomplishment of ultimate good without an accompanying possibility of evil.

The place where a ba’al teshuvah, a penitent sinner, stands, according to Rabi Abahu, “is a place where even the perfectly righteous cannot stand.” (Berachos 34b).

An old Chassidic tune’s words may say it best:

“Why, oh, why has the soul descended? / From so high a place to so one so low? / Because the descent is necessary for ascending.”

© 2023 Rabbi Avi Shafran