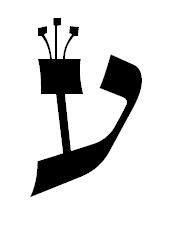

All the letters of the Hebrew alphabet are found in the bracha that Yehudah is given by his father Yaakov – with one exception: the zayin.

That fact is pointed out by Rabbeinu Bachya, who notes that zayin is not only a letter but a word – meaning “sword” or, more generally, “weapon.”

He writes:

“The reason is that the malchus Yisrael, which emerges from Yehudah, will not score its essential victory through the use of weapons like [ victories achieved by] other nations. Because the sword is Esav’s heritage but [not] that of the Jewish malchus, which will not inherit the land with their swords. And is not conducted by natural means, with the strength of the hand – but rather, through the… sublime power of Hashem.

And that is why one finds in the name Yehudah, the source of the Jewish kingdom, the letters of Hashem’s name…”

That fundamental message is always important to internalize, but it is particularly timely today. We have seen, in the Jewish fight against unspeakable evil, failures of military tactics, intelligence and weaponry, and the use of the latter bringing only more hatred against Klal Yisrael.

May we soon merit to see the success that can ultimately only come from Above.

© 2023 Rabbi Avi Shafran