My most recent Ami Magazine piece can be read here.

My most recent Ami Magazine piece can be read here.

A rumination on the meaning of “Palestinian” can be read here.

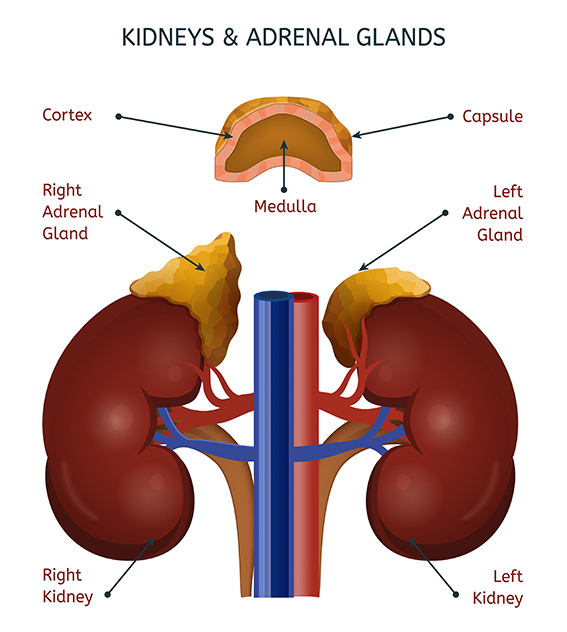

Among the eimorim, the portions of non-olah animal korbanos that are burned on the mizbe’ach, in contrast to the animal’s meat, which is eaten, is the cheilev she’al hak’layos – the “fat atop the kidneys.”

That reference is not to “fat” as we define the word, but, rather, to the yellowish glands that sit upon the kidneys of mammals and birds. That is to say, the adrenal glands.

Those structures are what produce epinephrine, also known as adrenaline, which plays the dominant role in the “acute stress response,” often called the “fight-or-flight” reaction, to a danger.

Epinephrine might be thought of as an “amplifier” or “heightener” of a body’s readiness to act. When produced, it causes pupils to dilate, allowing more light to be sensed; it opens airways wider; it directs blood to muscles and makes hearts pump harder and faster.

We don’t know, of course, how korbonos “work,” what effects they have in the spiritual realm. And those who offered them can be assumed to have lacked knowledge of what physiological effects the “fat atop the kidneys” have on organisms. But it can certainly be argued that korbonos are, if not exclusively then largely, expressions of determination and decisiveness, of readiness to take action.

And so it’s intriguing that the cheilev she’al hak’layos are associated physiologically with “acute stress response,” or what we might deem a “call to action.”

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

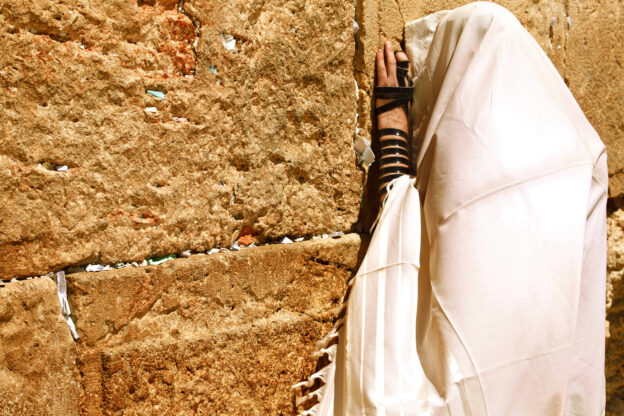

It’s intriguing that, just as Chazal place importance on being masmich geulah litfillah – placing a reference to redemption immediately before prayer, i.e. the amidah (Berachos 4b, 9b) – we find something similar in the Torah itself.

The first part of Sefer Shemos, the Torah’s book of geulah, concerns, of course, Yetzias Mitzrayim, the redemption from Egypt. And the latter parshios deal with the mishkan, the place of korbanos, which were accompanied by, and eventually replaced by, tefillah. And the sefer is followed by Vayikra, the sefer of korbanos.

What’s more, the segue into the concept of tefillah is hinted at as well in the final parsha of Shemos. As the Yerushalmi notes, there are 18 times in parshas Pekudei that the phrase “as Hashem commanded Moshe” is used, corresponding to the 18 brachos of the amidah. (And the phrase “as Hashem commanded” occurs without an object once, which could correspond to the added nineteenth bracha, birchas haminim.)

And, although the Gemara regards the introduction to the amidah, the short prayer “Hashem, open my lips and let my mouth speak Your praises,” as part of tefillah, it, too, may itself hint at the geulah, since the word for “my lips” is rooted in the word for the seashore, the “al sfas hayam” of kri’as Yam Suf we reference in Shacharis leading up to the bracha of Go’al Yisrael.

Why being masmich geulah litefillah is a desideratum isn’t obvious, but it might be because, as we are about to beseech Hashem, hakaras hatov, recognition of His favor toward us, embodied in the concept of geulah, is something on which to concentrate..

May our tefillos lead, in turn, to the geulah ha’asidah.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

An opinion column I wrote for the Boston Globe appeared on March 21 and can be read here.

A famous palindromic word in the Torah is venasnu, in the second pasuk in the parsha. It means “and each man must give,” in the context of contributing the machatzis hashekel, which the Torah describes as “monetary atonement for [the giver’s] life” (Shemos, 30:12). The word reads the same forward and backward.

The Baal HaTurim sees that as a hint to the Gemara’s contention that one should “tithe so that you will become wealthy” (Taanis, 9a), that giving charity will result in the giver’s benefit .

The Vilna Gaon discerned a somewhat different message in the palindrome, namely, that life plays havoc with fortunes, and therefore giving tzedakah to others will merit others’ supporting us or our descendants in our times of need. What goes around, in other words, comes around.

He cites the Gemara in Shabbos 151b:

“Rabbi Ḥiyya said to his wife: When a poor person comes to the house, be quick to give him bread so that they will be quick to give bread to your children. She said to him: Are you cursing your children?

He said to her: the yeshiva of Rabbi Yishmael taught that galgal hu shechozer ba’olam – it is a ‘cycle that repeats in the world’.”

In other words, wealth and destitution come and go, in individual lives and in family lines. Great fortunes are made and lost, and rags can lead to riches.

Media mogul and billionaire Oprah Winfrey was born into an impoverished family in Mississippi; she went to college on a scholarship.

Socialite Jocelyn Wildenstein, who inherited billions from her art dealer husband, died dependent on $900 Social Security payments.

And those people’s descendants might find themselves in entirely different statuses from their antecedents. Wealth recycles, something to remember when approached by a beggar.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

No matter our desire to embrace a country or leader as a truly reliable friend, we all — especially we Jews — do well to remember that there may not be any such thing, a truism about which Chazal warned us millennia ago.

To read what evoked that thought, please click here.

The imperatives of civility and refined speech are strongly stressed in the Talmud and in halacha. Yet, like all ideals, even those have their limits. An exception – the only one – to the imperative to avoid verbalizing crude characterizations is when it comes to idolatry.

As Rav Nachman says (Megillah 25b): “All mocking obscenity is forbidden except with reference to idol worship.” And the examples the Gemara offers are almost all about defecation. The characterization of all idolatry as “avodas gilulim” in various places in Tanach may also be intended as a scatalogical reference, since galal is a word for biological waste.

And then there is the specific case of Pe’or, the major idolatry whose entire service involves hallowing the act of defecation itself.

Rav Shimon Schwab, zt”l, brings up Rav Nachman’s dictum to suggest an intriguing understanding of one of the bigdei kehunah, the “priestly garments.” Rashi points out that it seems to him that the garment is apron-like, but worn in reverse of how aprons are usually worn, tied in the front with the bib in the back.

The Gemara, Rav Schwab reminds us, assigns an atonement that is effected by each of the bigdei kehunah. The ephod atones for the sin of idolatry (Arachin 16a).

Idolatry, notes Rav Schwab, is ultimately about worship of the physical, about veneration of the base. And that is why, as per Rav Nachman’s statement, it is derided by the navi, and permitted to be derided by us, as scatalogical in its essence.

And so, he then posits, it is fitting that the ephod, the beged kehunah that atones for the sin of idolatry, is worn, oddly, in a way that covers the wearer’s lower back, subtly recalling its particular role among the bigdei kehunah.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Last Thursday, explosives destroyed three buses in Israel – empty ones. Yesterday, Nael Obeid, a notorious Hamas terrorist who was freed in a hostage exchange, fell to his death in East Jerusalem. As we prepare to welcome Adar, we pray for Hashem’s continued protection.

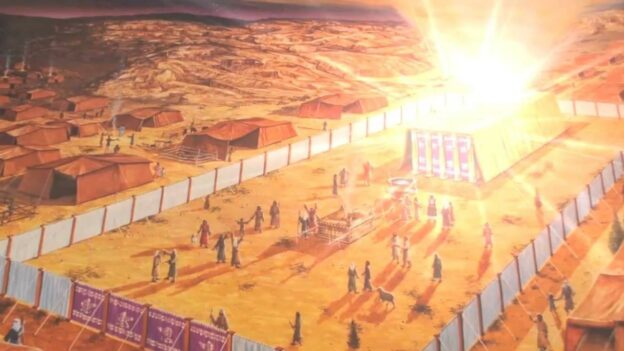

The word mikdash in the pasuk “They shall make for Me a mikdash so that I may dwell among them” (Shemos 25:8) should, by reason, be mishkan, as various meforshim point out. It is, after all, a directive to build the mishkan, the temporary sanctuary not the final edifice, the Beis Hamikdash.

Another anomaly in the pasuk is the change of object, from “They shall make for me a mikdash” to “and I will dwell in them.”

The simple approach to that latter incongruity is that the second phrase is, in effect, a new sentence, and that its object (the people) is different from the object of the first sentence (the mikdash). So that the pasuk is rendered: “Let them make me a mikdash. [And that structure will make it possible for me] to dwell among [the people].”

What occurs, though, is that a key to the second curiosity may lie in the earlier problem, the unexpected use of mikdash for the mishkan.

To wit: The mishkan may not actually be a mikdash, but kiddush is what it does: It effects a kiddush Hashem. It declares Hashem’s glory to the people and the world.

We Jews are charged with being mekadshei Hashem, too. Not only, when required, to die al kiddush Hashem, but also to live al kiddush Hashem, to proclaim, by our demeanor and deeds, the glory of Hashem to other Jews and beyond.

So perhaps the use of the word mikdash for the mishkan is meant not to define the structure but, rather, to describe what it does. And the second part of the pasuk could be alluding to the fact that what the mishkan does – namely, creates kiddush Hashem – is what we as Jews are likewise to do in every era of history, that we are to be walking, talking batei mikdash – mekadshei Hashem.

And so, as a result, Hashem says, vishachanti bisocham, I will dwell in them, in their essences, in who they are, mekadshei Hashem.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran