“We used to spend a good two hours here… chaos,” Palestinian construction worker Imad Khalil explained to National Public Radio’s Daniel Estrin. “Today we arrive and we immediately pass.”

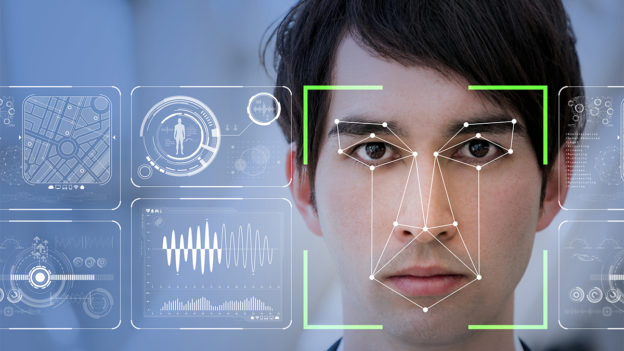

The worker was marveling at the efficiency of “Speed Gate,” a facial recognition technology that has done away with crowds and individual inspections by Israeli soldiers at checkpoints through which Arab day laborers must pass from Yehudah and Shomron to work in Israel proper. Nearly 100,000 Palestinian laborers cross such checkpoints daily.

Where the technology is in place, the workers now need only place electronic ID cards on a sensor and stare at a camera. Panels then open to let them through.

Palestinians wishing to work in Israel have for many years been photographed and fingerprinted, in order to ascertain that they have nothing in their records to indicate they’re a threat to anyone.

Having soldiers ascertain identities of crossing workers created long lines and frustrated people. The new facial recognition software allows workers’ ID cards to immediately connect to a biometric database and confirm their identities in an instant.

Israel is also building a database of its own citizens, and already uses similar facial recognition technology for passport control at Ben Gurion airport.

As might be expected, human rights advocates are upset by the effort, seeing it as helping perpetuate the current political status quo and as a violation of individuals’ privacy.

Omer Laviv of Mer Security and Communications Systems, an Israeli company that markets the technology to law enforcement agencies internationally, had four words in response to such anxieties: “Security concerns override privacy.”

Several thousands of miles to the west, in New York City, the city’s police department use of identification technology is likewise being criticized by privacy advocates.

The department has not only built a giant facial recognition database and loaded thousands of arrest photographs, including of children and teenagers, into it, but was recently revealed to have accelerated the collection and storage of criminals’ and suspects’ DNA, obtained from cheek swabs or even from coffee cups, water bottles or cigarette butts harboring trace amounts of suspects’ saliva.

There are currently more than 80,000 genetic profiles in the city database, begun in 2009, an increase of 28 percent over the past two years. Scores of violent crimes have been successfully prosecuted based on collected DNA.

The criticism, from groups like the Legal Aid Society, has focused on the fact that some 30,000 of the profiles are of people, including minors, who were only suspected of crimes, but never convicted.

Some civil liberties lawyers contend that taking someone’s DNA without probable cause to suspect that they did something illegal violates the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth Amendment’s ban on “unreasonable searches and seizures.” The legitimacy of that assertion depends on the meaning of “searches and seizures.” DNA and facial recognition technology were things unimagined, likely unimaginable, to the Constitution’s crafters.

But is there anything qualitatively different between fingerprinting a suspect – or just photographing him – and recording the patterns of his DNA? While DNA identification is not, in many cases, at all as indisputable as most people assume – there are a number of issues that can render it less than conclusive – it is certainly a most useful tool in better focusing investigations that can lead to more decisive evidence.

And there can be little doubt that not only does “searches and seizures” in the Fourth Amendment need a modern definition; so does the word “unreasonable.

There may well be activists who maintain that street cameras should be considered unlawful, or who shun EZ-Pass or GPS technology because they consider such things, which identify users’ locations and movements, dangers to individual privacy. But, justified in their fears or not, they are blowing hard at a hurricane.

Because, like it or not, we no longer have private lives, at least not in the sense of being invisible to a plethora of commercial, governmental or law enforcement entities. Cameras on the sides of buildings, and inside them, abound. Anyone with a driver’s license or passport has surrendered information to authorities, and anyone who uses the internet is shedding dribs and drabs of facts about himself to untold numbers of commercial and other interests.

That might dismay some people, but it is, in the end, a simple fact of modern life. And leveraging technology to fight crime – as long as it is done responsibly and with recognition of new tools’ limits – doesn’t strike me as unreasonable. Even if a youngster’s DNA is on file in a police database, well, youngsters grow up, after all, some of them, sadly, into violent criminals. And a means of identifying a perpetrator of a crime is something beneficial to society.

For Jews who recognize the truth of the Jewish mesorah, the new technologies can serve to remind us that, as Rabi Yehudah Hanasi stresses in Avos (2:1): “An eye sees and an ear hears…”

And, particularly apt, with the Yamim Nora’im still fresh in our memories, “…all of your actions are in the record written.”

© 2019 Hamodia