“An ugly chapter in voter suppression is finally closing,” declared Dale Ho, director of the A.C.L.U.’s Voting Rights Project.

He was referring to the U.S. Supreme Court’s declining last week to judge a North Carolina voting law that a federal appeals court had struck down as an unconstitutional effort to “target African-Americans with almost surgical precision.”

The law, enacted in 2013, effectively rejected forms of voter identification used disproportionately by blacks, like IDs issued to government employees, students and people receiving public assistance. It was part of a wave of voting restrictions that followed in the wake of Shelby vs. Holder, that year’s 5-to-4 Supreme Court decision overturning a requirement that certain states with histories of voter discrimination obtain preclearance from a federal court before making changes to their voting laws.

The federal appeals court also noted that North Carolina had “failed to identify even a single individual who has ever been charged with committing in-person voter fraud” in the state and that the only evidence of fraud was in absentee voting by mail, a method that was both exempted by the law and is used disproportionately by white voters.

The court also found that the law’s restrictions on early voting had a much larger effect on black voters, who “disproportionately used the first seven days of early voting,” the result of free rides to polling places offered by black churches on “Souls to the Polls” Sundays. (Note to Agudath Israel voting drive officials: See if that slogan’s been copyrighted!)

Last week’s Supreme Court decision not to revive the North Carolina case, however, turned on procedural issues, not on the substance of the suit, so the now-full-bench court’s current leanings remain unknown.

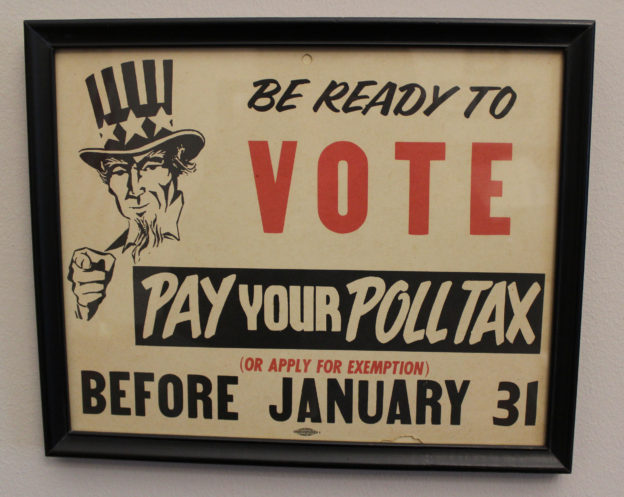

Attempts to curtail blacks’ ability to vote are a regrettable part of American history. They took the form of things like literacy texts and poll taxes.

And, of course, at the founding of the republic, neither women nor members of various religious groups (ours included) were eligible to vote. Only in 1920 were women allowed to vote in all federal and state elections; and only in 1964 were poll taxes outlawed.

Interestingly, there is no explicit “right to vote” in the U.S. Constitution. What the country’s foundational legal document includes, in various amendments, are prohibitions against certain forms of discrimination in establishing who may vote. It is a distinction with a difference, if a subtle one.

Voting in America is a privilege, not something any American can claim a right to, as he can to speak or worship freely, or to a speedy trial. And that means that restrictions, if they don’t discriminate against any group or to favor a political party, are perfectly acceptable.

Likely heading for the Supreme Court now, though, is a Texas law requiring photo identification. A district judge and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit have declared the law discriminatory, even though it accepts seven types of photo ID and can be satisfied by a voter presenting a utility bill or paycheck and signing a form asserting that they have a “reasonable impediment” preventing the obtaining of a photo ID.

A similar law was recently enacted in Iowa. Ari Berman, a writer for The Nation, wrote a piece titled, “Iowa’s New Voter ID Law Would Have Disenfranchised My Grandmother,” about his late bubby, a Holocaust survivor who moved from Brooklyn to Iowa (go figure) when she was 89.

She had no driver’s license, birth certificate or passport; thus, Mr. Berman contends – well, his article’s title finishes the sentence.

Iowa’s law, however, specifies that the state Department of Transportation will provide free voter IDs to voter registrants who don’t already have state-issued identification. So Berman’s bubby, aleha hashalom, would have no trouble registering and voting today.

Does widespread voting fraud exist? President Trump’s repeated claims notwithstanding, no. Does that mean that laws to prevent it are wrong? No, again. Are voting restrictions racist or reasonable? Well, they can be either.

And yet, as things go in our black-and-white world, when it comes to voting requirements, Democrats and Republicans; minority advocates and establishment types; liberals and conservatives, all line up their regular armies, giving orders to take no prisoners and make no concessions.

A judicious person – a characterization to which each of us should aspire – doesn’t fall into formation on either side of such issues. There are distinctions to be made, nuances to discern, factors to weigh. Tasks that, here, will fall eventually to the land’s highest court.

© 2017 Hamodia