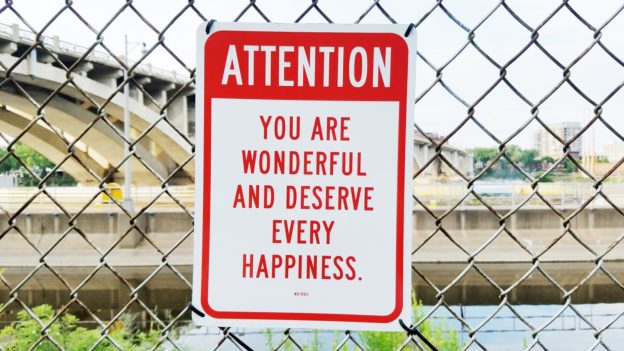

I used to pass the fellow each morning as I walked up Broadway in lower Manhattan on my way to work. He would stand at the same spot and hold aloft, for the benefit of all passers-by, one of several poster-board signs he had made. One read “I love you!” Another: “You are wonderful!” The words of the others escape me, but the sentiments were similar.

He looked normal and was decently dressed, and he smiled broadly as he offered his expressions of ardor to all of us rushing to our offices. I never knew what had inspired his mission, but something about it bothered me.

Then one day I put my finger on it. It is ridiculously easy to profess love for all the world, but it is simply not possible. Gushing good will at everyone is offering it in fact to no one at all.

By definition, love must exist within boundaries, and our caring for those close to us is of a different nature than our empathy for others with whom we don’t share our personal lives. What is more, only those who make the effort to love their immediate families and friends have any chance of truly caring, on any level, about others.

Likewise, those with the most well-honed sense of concern for their own communities are the ones best suited to experience true empathy for people outside of their communal worlds.

It’s an appropriate thought for this time of Jewish year, as Sukkos gives way, without a second’s pause, to Shemini Atzeres.

Sukkos, interestingly, includes something of a “universalist” element. In the times of the Beis Hamikdash, the seven days of Sukkos saw a total of seventy parim offered on the mizbeiach, corresponding, says the Gemara, to “the seventy nations of the world.”

The families of people on earth are not written off by our mesorah. A mere four days before Sukkos’s arrival, on Yom Kippur, we read Sefer Yonah. That navi was sent to warn a distant people to repent, saving them from destruction. The Sukkos parim, the Gemara informs us, brought divine blessings down upon all the world’s peoples. Had the ancient Romans known just how greatly they benefited from the merit of karbanos, Chazal teach, they would have placed protective guards around the Beis Hamikdash.

And yet, curiously, Sukkos’s recognition of humanity’s worth is juxtaposed with Shemini Atzeres, which expressed Hashem’s special relationship with Klal Yisroel.

The famous parable:

A king invited his servants to a large feast that lasted a number of days. On the final day of the festivities, the king told the one most beloved to him, “Prepare a small repast for me so that I can enjoy your exclusive company.”

That is Shemini Atzeres, when Hashem “detains” the people He chose to be an example to the rest of mankind, when, after the seventy parim of the preceding seven days, a single par, corresponding to Klal Yisroel, is brought on the mizbeiach.

We Jews are often assailed for our belief that Hashem chose us from among the nations to proclaim His existence and to call on all humankind to recognize our collective immeasurable debt to Him.

And those who are irritated by that message like to characterize the special bond Jews feel for one another as hubris, even as contempt for others.

The very contrary, however, is the truth. The special relationship we Jews have with each other and with HaKodosh Boruch Hu, the relationships we acknowledge in particular on Shemini Atzeres, are what provide us the ability to truly care – not with our mere lips or poster boards – about the rest of the world. They are what allow us to hope – as we declare in Aleinu thrice daily – that, even as we reject the idolatries that have infected the human race over history, one day “all the peoples of the world” will come to join together with us and “pay homage to the glory of Your name.”

© 2022 Ami Magazine