Considering that a

survey last year revealed that 31 percent of Americans, and 41 percent of

millennials, believe that two million or fewer Jews were killed in the

Holocaust, and that 41 percent of Americans, and 66 percent of millennials,

cannot say what Auschwitz was, a large and impressive Holocaust exhibit would

seem to merit only praise.

And praise the “Auschwitz. Not Long Ago. Not Far Away” exhibit currently

at the Museum of Jewish

Heritage in Manhattan

has garnered in abundance. It has received massive news coverage in both print

and electronic media.

First shown in Madrid,

where it drew some 600,000 visitors, the exhibit will be in New York into January before moving on.

Among many writers

who experienced the exhibit and wrote movingly about its power was reporter and

author Ralph Blumenthal. In the New York Times, he vividly described the

artifacts that are included in the exhibit, which includes many items

the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

in Poland

lent for a fee to the Spanish company Musealia, the for-profit organizer of the

exhibition.

Mr. Blumenthal wrote that the museum, within sight of Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty, had to alter its

floor plan to make room for large-scale displays like a reconstructed barracks.

Outside the museum’s front door, there is a Deutsche Reichsbahn railway cattle

car parked on the sidewalk, placed there by a crane.

Inside, among the 700

objects and 400 photographs and drawings from Auschwitz, are concrete posts and barbed wire that were once part of the

camp’s electrified perimeter, prisoners’ uniforms, three-tier bunks where ill

and starving prisoners slept two or more to a billet, and, “particularly

chilling,” an adjustable steel chaise for medical experiments on human beings.

There is a rake for ashes and there are heavy iron crematory

latches, fabricated by the manufacturer Topf & Sons There is a fake

showerhead used to persuade doomed victims of the Nazis, ym”s, that they were entering a bathhouse, not a death chamber

about to be filled with the lethal gas Zyklon B.

And personal items, like a child’s shoe with a sock stuffed

inside it.

“Who puts a sock in his shoe?” asks Mr. Blumenthal. “Someone,” he explains poignantly, “who

expects to retrieve it.”

Another essayist, this one less impressed by the exhibit –

at least in one respect –is novelist and professor Dara Horn, who teaches

Hebrew and Yiddish literature.

Writing in The

Atlantic, Ms. Horn approached the exhibit carrying in her mind the recent

memory of a swastika that had been drawn on a desk in her children’s New Jersey public middle

school and the appearance of six more of the Nazi symbols in an adjacent town.

“Not a big deal,” she writes. But the scrawlings provided a personal context

for her rumination on her museum visit.

In her essay, titled “Auschwitz Is Not a Metaphor: The new

exhibition at the Museum of Jewish Heritage gets everything right – and fixes

nothing,” she recalls her visit to Auschwitz as a teenager participating in the

March of the Living, and reflects on Holocaust museums, which she characterizes

as promoting the idea that “People would come to these museums and learn what

the world had done to the Jews, where hatred can lead. They would then stop

hating Jews.”

And the current exhibit, she notes, ends with a similar

banality. At the end of the tour, she reports, “onscreen survivors talk in a

loop about how people need to love one another.”

To do justice to Ms. Horn’s reaction would require me to

reproduce her essay in full. But a

snippet: “In Yiddish, speaking only to other Jews, survivors talk about their

murdered families, about their destroyed centuries-old communities… Love rarely

comes up; why would it? But it comes up here, in this for-profit exhibition.

Here is the ultimate message, the final solution.”

Ouch.

“That the Holocaust drives home the importance of love,” she

writes further, “is an idea, like the idea that Holocaust education prevents

anti-Semitism, that seems entirely unobjectionable. It is entirely

objectionable.”

Those sentences alone would make the essay worth

reading. And the writer’s perceptivity

is even more in evidence when she writes:

“The Holocaust didn’t

happen because of a lack of love. It happened because entire societies

abdicated responsibility for their own problems, and instead blamed them on the

people who represented –have always represented, since they first introduced

the idea of commandedness to the world – the thing they were most afraid of:

responsibility.”

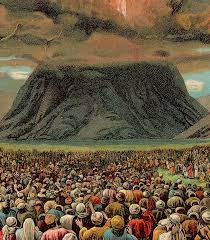

Har Sinai is called that, Rav Chisda and Rabbah bar Rav Huna

explain, because it is the mountain from which sinah, hatred, descended to the nations of the world. (Shabbos 89a). One understanding of that statement is

precisely what Ms. Horn contends. Although her essay appeared the week before

Shavuos, she didn’t intend it to have a Yom Tov theme.

But in fact it did.

© 2019 Hamodia