My most recent Ami Magazine piece can be read here.

My most recent Ami Magazine piece can be read here.

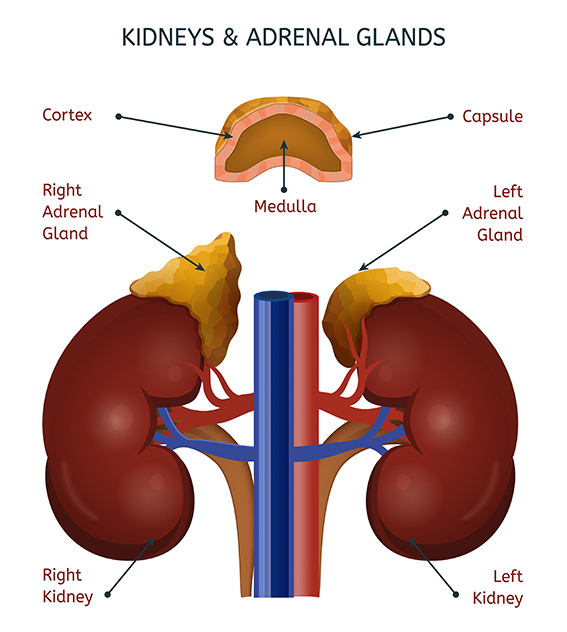

Among the eimorim, the portions of non-olah animal korbanos that are burned on the mizbe’ach, in contrast to the animal’s meat, which is eaten, is the cheilev she’al hak’layos – the “fat atop the kidneys.”

That reference is not to “fat” as we define the word, but, rather, to the yellowish glands that sit upon the kidneys of mammals and birds. That is to say, the adrenal glands.

Those structures are what produce epinephrine, also known as adrenaline, which plays the dominant role in the “acute stress response,” often called the “fight-or-flight” reaction, to a danger.

Epinephrine might be thought of as an “amplifier” or “heightener” of a body’s readiness to act. When produced, it causes pupils to dilate, allowing more light to be sensed; it opens airways wider; it directs blood to muscles and makes hearts pump harder and faster.

We don’t know, of course, how korbonos “work,” what effects they have in the spiritual realm. And those who offered them can be assumed to have lacked knowledge of what physiological effects the “fat atop the kidneys” have on organisms. But it can certainly be argued that korbonos are, if not exclusively then largely, expressions of determination and decisiveness, of readiness to take action.

And so it’s intriguing that the cheilev she’al hak’layos are associated physiologically with “acute stress response,” or what we might deem a “call to action.”

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

| Have you heard of Perkycet®️? No? Well read all about it, and about drug ads, here. |

It could have been a launch pad for a vehicle to reach the moon. Or a panopticon to monitor people over a large distance. Those are two of the suggested theories for why the people of Bavel sought to build an unprecedentedly tall tower. The first suggestion was put forth by Rav Yonasan Eibschutz; the second, by the Netziv.

Whatever the builders’ aim was, though, it was a development that, as the Torah recounts, merited divine interference. But the words introducing the endeavor are strange. The would-be builders said to one another:

“‘Come, let us mold bricks and bake them well.’ They then had the bricks to use as stone, and the clay for mortar” (Beraishis, 11:3).” What is the significance of their mode of construction?

In 1927, Tomáš Masaryk, then-president of then-Czechoslovakia and a leader friendly to Jews, visited the Yishuv in Eretz Yisrael and was received by its leader, Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld.

According to the book about Rav Sonnenfeld, Ha’ish al Hachomah, one of the things he discussed with the European leader was the danger posed by technological advances. And he pointed to the pasuk above as an example of how such progress is often born of a misguided attempt to deny the ultimate importance of Hashem. The Bavel builders, he explained, shunned the natural stone available to them, opting instead for their advanced “brick technology.” In so doing, they were declaring their “independence” from the divine.

I’m reminded of the story of the group of scientists who inform Hashem that His services are no longer needed, that their knowledge of the universe now allows them to run it just fine themselves, thank You.

“Can you create life like I did?” the Creator asks. “No problem,” they reply as they confidently gather some dirt and fiddle with the settings on their shiny biologocyclotron.

“Excuse Me,” interrupts the heavenly voice. “Get your own dirt.”

Or, as Carl Sagan said, “If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.”

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Is there any reason why the Torah uses the definite article (“the”) in its first pasuk? Couldn’t it have said “In the beginning, Elokim created heavens and earth” – minus the “the”s?

While we can never truly know what transpired at the dawn of creation – Mishlei 25:2 says “The honor of Elokim is hiding the thing,” which Rabi Levi in the name of Rabi Chama bar Chanina (Beraishis Rabbah 9:1) applies to the creation week – it’s reasonable to assume that “heavens” refers to space (Rav Hirsch sees the word shomayim as referring to all the “shom”s – the “theres” in all directions); and “earth,” to matter (and, perhaps, what we call energy). So what’s with the “the”s?

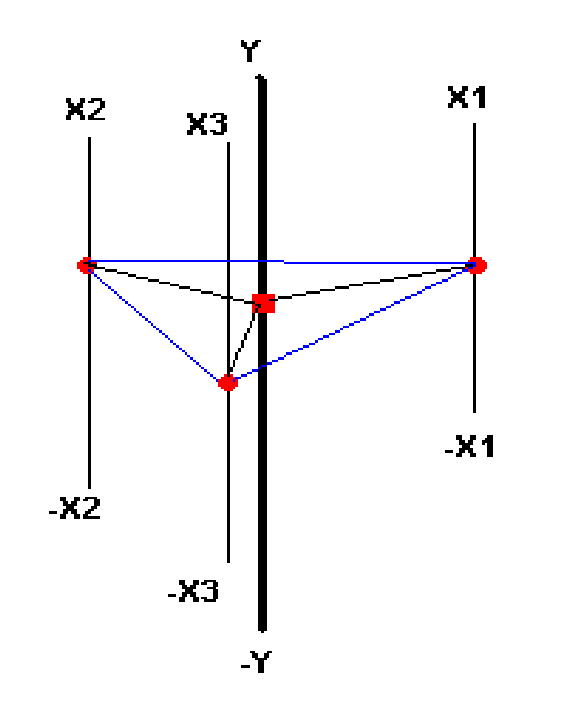

I raise the question not to answer it, rather only to ruminate on that Hebrew letter, the one that serves to mean “the” or “that” – the letter hei.

The universe Hashem created, to the best of our perception, has three spatial dimensions and one temporal one. To pinpoint an object, one has to identify its three axes in space and its “place” in time.

To get a fix on a hot air balloon, for instance, we must know its longitude, latitude and altitude; and when it is there.

Which leads to an interesting observation: After the first four letters of the Hebrew alphabet, which might correspond to our four-dimensional universe, we have its fifth, the letter that is used as a prefix to mean “the” or “that” – the words we use to point to a particular thing.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

As is the case with any question about nature, when a child asks why the sky is blue, the answer you give (here, that blue light is scattered more than other colors) will elicit a subsequent why (because it travels as shorter, smaller waves); and then that answer will yield yet another question: Why is that? Eventually, the final answer is “That’s just the way it is!” In other words, it’s Hashem’s will.

Rav Dessler famously explained that all of nature, no less than a sea splitting, is ultimately a miracle, an act of G-d. What we call miraculous is just a divine-directed happening we’re not used to seeing.

The season of teshuvah, in our Torah-reading cycle, coincides with our parshah, in which we read: “And you will return to Hashem…” (Devarim 30:2).

The most fundamental element of nature, arguably, is time. The past is past, and time proceeds into the future relentlessly. But time itself, too, is a divine creation. Commenting on the Torah’s first words, which introduce Hashem’s creation, “In the beginning…,” Seforno writes: “[the beginning] of time, the first, indivisible, moment.”

And time, too, like the rest of nature, can be manipulated by Hashem’s will. Indeed, as it happens, by our own as well.

Because teshuvah, Chazal teach us, can change past intentional sins into unintended ones. Even, if the teshuvah is propelled by love of Hashem, into merits.

Is that not a changing of the past, the temporal equivalent of splitting a sea?

And that ability to manipulate time may be why, on Rosh Hashanah, unlike on every other Jewish holiday, the moon, the “clock” by which we count the months of the year, is not visible. What’s being telegraphed may be the idea that time need not limit us, if we properly engage the charge of the season.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Can you remember the last time a consumer of rats merited an obituary in The New York Times? Me neither. But there recently was one, and you can read my thoughts about Flaco the owl here.

A piece I wrote for Religion News Service about “brain death” can be read here.

Seizing on the fact that the Hebrew word for a granary – osem – shares two letters with the word for “obscured” – samui – Chazal make an intriguing assertion: Blessing [i.e. increase in volume] is common only in things that are “obscured from the eye” (Bava Metzia 42a).

The pasuk on which that truth is based is in our parsha: “Hashem will order the blessing to be with you in your granaries [ba’asamecha]…” (Devarim, 28:8).

Rav Dessler (first chelek of Michtav M’Eliyahu, pg. 178 in my ancient edition) explains that what we call cause and effect, the essence of physics, is really an illusion; only Hashem’s will is operative, even in what we call physical nature. And so, when something is out of sight, where cause and effect cannot be perceived, His will can cause bracha in the hidden.

That idea of natural law’s suspension in the case of something beneath perception is vaguely, but tantalizingly, reminiscent of quantum physics’ “Schrödinger’s cat” thought experiment, where direct cause and effect is seemingly suspended – on the subatomic level, but with theoretical implications for the macroscopic world. The issue underlying Schrödinger’s paradox remains an unsolved problem in physics.

Be that as it may, though, something important will in fact be “obscured from the eye” in a few weeks: the moon, on Rosh Hashana. The moon is Klal Yisrael’s timekeeper, and time is the most fundamental element of nature. Klal Yisrael’s clock will not be visible on the first of the days of teshuva.

And time itself, in a sense, will be suspended then. Because we can interfere with its natural, relentless march forward – or, at least, with its unreachable past. Through the bracha of teshuva, which Chazal tell us can change the very nature of our pasts, traveling back, in a way, in time – turning past wrong actions done intentionally into actions done inadvertently; even, with the deepest teshuva, repentance born of pure love of Hashem, into meritorious acts.

© 2023 Rabbi Avi Shafran

A longform piece I wrote about the Noble Prize laureate physicist I.I. Rabi was published by Tablet, and can be read here.