A longform piece I wrote about the Noble Prize laureate physicist I.I. Rabi was published by Tablet, and can be read here.

A longform piece I wrote about the Noble Prize laureate physicist I.I. Rabi was published by Tablet, and can be read here.

I always look forward to feedback on columns, whether the responses are positive or critical. The former keep me writing; the latter help me learn.

On occasion, though, a response is just…well…odious.

Like one that I wrote about in last week’s Ami column, which you can read here.

Kol yimei chayecha – “All the days of your life” – is a phrase we first meet in the Torah when Hashem pronounces the fate of Adam after the sin of eating from the eitz hadaas: “Cursed is the ground because of you. Through suffering will you eat from it all the days of your life” (Beraishis 3:17).

The phrase recurs in a seemingly unrelated context, about the mitzvah of eating matzah on Pesach, in our parsha: “…so that you will remember the day you left Egypt all the days of your life” (Devarim 16:3).

That pasuk, cited in the Haggadah, elicited a novel thought from Rav Avrohom, the first Rebbe of Slonim: “When recounting Yetzias Mitzrayim, one should remember, too, ‘all the days’ of his own life – the miracles and wonders that Hashem performed for him throughout…”

The generation before mine, the one that came of age during the Second World War, could well relate to that idea. My father endured years of forced labor in Siberia, courtesy of the Soviet Union. My father-in-law was a veteran of several concentration camps, and suffered the deprivations and tortures for which they are infamous.

And, I know, on Pesach, thoughts of their experiences were in their minds. My father and his friends pocketing and then hiding a few wheat kernels here and there, to be secretly ground and baked in the middle of the night into matzos. My father-in-law, in a Dachau satellite camp, reciting with a friend parts of the Haggadah they knew by heart.

But the Slonimer Rebbe’s thought is appropriate for every life, even lives of relative calm and plenty like our own. Because, as a result of the sin of the eitz hadaas, adversity and tragedy entered the world and came to define all humans’ lives, to one or another extent. We all have experienced things that were daunting or worse, and from which we were saved. We may not have been liberated from a literal gulag or camp, but we are all, on one or another level, survivors.

And we need to consciously recall that fact, all the days of our lives.

© 2023 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Last week, President Biden issued a presidential proclamation recognizing the horrific injustice that was the murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old whose brutal killing in Mississippi in 1955 helped galvanize the civil rights movement. A national monument is being created in honor of the murdered boy and his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, who forced the nation to confront the horror of what happened to her son.

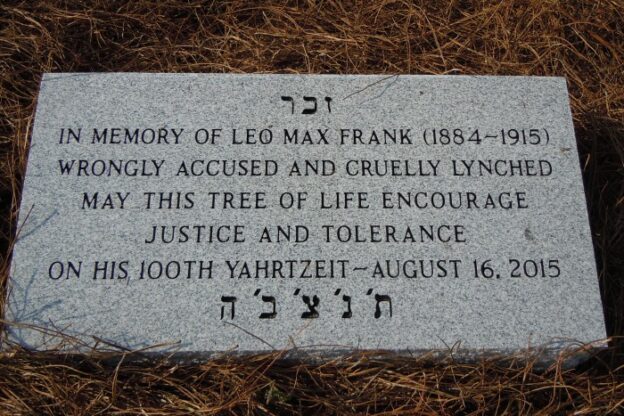

What the revisiting of that evil brought to my mind was another lynching, of a Jewish man in Georgia decades earlier, in 1915. The murder of Leo Frank is a sad part of American history that should not be forgotten.

On April 26, 1913, a 13-year-old girl on her way to Atlanta’s Confederate Memorial Day parade stopped at her place of employment, the National Pencil Company, to collect her paycheck. The next day, she was found murdered in the factory’s basement.

Leo Frank, a 29-year-old Jewish man, was working at the factory that morning and handed the girl her pay. He was the last person to see her and so, when the murder was discovered the next morning, he came under suspicion and was arrested and jailed.

Police, however, had another suspect. Jim Conley, a custodian at the factory, who a witness saw in the factory basement washing out a shirt soaked with what appeared to be blood. Notes, filled with misspellings, were found alongside the murdered girl and Jim Conley was questioned.

After two weeks, he finally admitted writing the notes but said that Leo Frank had asked him to, and had confessed to the murder.

Conley signed contradictory affidavits, which were entered into the trial of Leo Frank. But the glaring inconsistencies were ignored by the jury.

As the trial took place, crowds gathered outside the courthouse chanting “Hang the Jew!”

Based on Conley’s claim and with no real evidence to implicate Frank, the four-week trial ended with a guilty verdict. Outside the courthouse, the crowd cheered the announcement. According to the New-York Tribune, the prosecuting attorney “was lifted to the shoulders of several men and carried more than a hundred feet through the shouting throng.”

The presiding judge, Leonard Roan, sentenced Frank to death by hanging. Appeals ensued for two years. And even after Conley’s former attorney said he believed his former client was the actual murderer, a retrial motion was also rejected.

The case ended up before the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in a 7-2 ruling, allowed Frank’s conviction to stand. Justices Oliver Wendall Holmes and Charles Evan Hughes dissented, stating that the hostility outside the courthouse influenced the conviction.

Georgia Governor John Slaton conducted his own extensive investigation into the case, and, on June 21, 1915, the day before Frank’s execution was to take place, commuted his sentence to life in prison. The governor wrote that “I would rather be plowing in a field than to feel that I had that blood on my hands.”

The community was outraged and Governor Slaton, whose term ended shortly thereafter, fled Georgia with his wife, fearful of the retribution local citizens might visit upon him for keeping the Jew alive.

On August 17, 1915, a mob of 25 men overpowered the guards at the prison farm where Frank was held and kidnapped him. They drove him some 100 miles to a grove near Marietta, handcuffed and hanged him. An approving crowd of some 3000 Georgians, including prominent local citizens, flocked to the lynching site, collecting souvenirs and taking photographs.

Nearly 70 years after the girl’s murder, on March 7, 1982, it was reported that Alonzo Mann, Leo Frank’s office boy, who was fourteen at the time of the killing, said that Conley had murdered the girl, and that he saw the custodian holding her. “If you ever mention this, I’ll kill you,” Conley had told him. Mann said that when he told his mother what he had seen, she told him to keep quiet. He did.

The new evidence led the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles to issue a pardon for Leo Frank – but only based on the state’s failure to protect him while in custody and for not bringing his murderers to justice. It did not, however, exonerate the innocent man.

A jury and judge, after all, had spoken.

© 2023 Ami Magazine

Back in 1988, I buried a Reform rabbi. Literally.

To read about who he was and why I undertook that holy task, click here.

Indigenousness is in the eye of the beholder

In an irony as rich as premium full-fat ice cream, Ben & Jerry’s, the frozen confection company that objected last year to its product being sold in indigenously Jewish land, found itself melting under consumer heat for asserting the rights of Indigenous Americans.

On the Fourth of July, the company posted a video on social media to celebrate “National Ice Cream Month.” (Now, that one’s definitely going on my calendar, though I’ll opt for a cholov Yisrael brand.)

But Ben and Jerry’s seized the opportunity, in line with its declared exquisite social conscience, to inform ice cream aficionados that “it’s high time we recognize that the US exists on stolen Indigenous land, and commit to returning it.”

The campaign was elaborated upon on Ben & Jerry’s website, which explained that its “land back” stance was about “ensuring that Indigenous people can again govern the land their communities called home for thousands of years.” It focused mainly on the taking of land, including Mt. Rushmore, from the Lakota tribe in South Dakota.

Oddly, though, Messrs. Cohen and Greenfield – the Ben and Jerry who founded the company in the 1970s – seemed less enamored of indigenous rights last year when they blasted the brand’s parent company Unilever for selling the franchise’s operations in Israel to a local licensee, which allowed the stuff to be sold in Yehudah and Shomron, in the ice cream kings’ view, “occupied territories.”

Those territories are “occupied,” in their view, by the evil colonizer Israel. But, whatever one’s thoughts about the future political status of those areas, from the standpoint of actual history – which seems important to Ben and Jerry – it is myopic to see them as indigenously Arab.

On the contrary, the only readily identifiable people today who have true historic claim of descent from the land’s most ancient inhabitants are Jews.

There are no Cna’anim left today. They were vanquished in Yehoshua’s time. With all due respect (what little is due) to P.A. President Mahmoud Abbas, who told the U.N. Security Council in 2018 that “we are the descendants of the Canaanites that lived in the land 5,000 years ago,” not only is his claim nonsense, but it’s also one that, tellingly, no Palestinian Arab (himself included) ever made over centuries. Mr. Abbas was trying to invent an imaginary indigenousness. Nice try, Mahmoud.

When the Jews who lived in the land since Yehoshua’s time were forced to leave it, something that we Jews have lamented for all the centuries since and focus on in particular these days every Jewish year, those who subsequently took up residence in Eretz Yisrael were the occupiers.

That includes the “Palestinians,” many of whom are in reality descended from successive waves of people who came to the area only at the end of the 18th century from places like Egypt, where famine and persecution fueled emigration; and, in the 19th century, from Algeria, Transjordan and Bosnia. So much for Arab indigenousness in Eretz Yisrael.

In the end, Unilever sold its Ben & Jerry’s division to another company that has rights to sell products in Israel and the territories overseen by the Palestinian Authority. Ben and Jerry were not happy. “We continue to believe it is inconsistent with Ben & Jerry’s values,” they tweeted, “for our ice cream to be sold in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.” They got licked.

And aren’t likely very happy now, either. Because many American consumers were apparently less than enthusiastic about the boys’ recent proposal that the nation be transferred to descendants of Native American tribes and go from being the United States of America to the Disunited Tribes of America. Ben and Jerry’s parent company lost nearly $2 billion in market capitalization in the wake of their July 4 message.

And adding sprinkles to the rich ice cream irony is an inconvenient fact of American history.

Before the establishment of the Republic, the Abenaki – a confederacy of various Indigenous tribes that united against a rival tribal confederacy – controlled an area that stretched from the northern border of Massachusetts in the south to New Brunswick, Canada, in the north, and from the St. Lawrence River in the west to the East Coast.

Ben & Jerry’s headquarters are located in a business park in southern Burlington, Vermont. Well within the western portion of Abenaki territory.

Delicious.

© 2023 Ami Magazine

There have been complaints about NYC Mayor Adams’ choice of representatives for his Jewish Advisory Council — to many Orthodox Jews, too few non-Orthodox ones. I make the case for the council as currently comprised, here.

In the wake of Israel’s recent raid on Jenin, various Arab and Islamic countries, playing as they must to their “streets,” registered their condemnation of the operation; the US State Dept. defended Israel’s right to proactively defend herself from terrorism. And members of Congress either joined that judgment or didn’t comment at all.

With one exception. No less repugnant than it was predictable.

You can read about the lone stand-out here.

In Moshe Rabbeinu’s parting rebuke of Klal Yisrael for “not believing in Hashem” (Devarim 1:32), for all its complaining in the wake of the report of the meraglim and beyond, he refers to Hashem’s decree that the “generation of the desert” will not get to see the promised land.

And then he says, “Hashem was also angry with me because of you, saying, ‘Neither will you go there’” (1:37).

“Also?” “Because of you?” What are those words saying?

Moshe, though, is more than the leader of the nation; he reflects it, embodies it. He is called a melech, a king. And Chazal tell us that ein melech b’lo am, there is no king without a nation. That means something beyond the obvious. It means that, in a way, the king isthe nation. Which is why a king has no right to forgo his honor (Kiddushin 32b); it is the nation’s honor.

And so, in a way, the “sin” that prevented Moshe from entering Cna’an, the striking of the rock to provide water, was a reflection, even embodiment, of the nation’s sin. How?

Moshe’s mistake was not hitting the rock but rather not speaking to it (as he was commanded).

And thereby not advancing kiddush shem Shomayim by conveying to the people (as per the Midrash Rashi brings in Bamidbar 20:12) the lesson that if an inanimate object fulfills Hashem’s mere words, His mere declaration of will, so much more so should human beings.

Instead, the idea unintentionally conveyed was that only punishment spurs heeding Hashem.

The people, apparently, weren’t ripe for the intended lesson. And so, Moshe’s act necessarily reflected that fact. Had Moshe spoken to the rock as ordered, Chazal say, he would have been able to enter Cna’an and there would never have been any exile of the Jews from their land.

Like the rock, we have been smitten – with the rod of galus and all its tribulations. May the lesson that the rock was meant to teach be internalized, quickly and in our day.

© 2023 Rabbi Avi Shafran

A recent interaction on a bus in Israel’s central district dovetailed with a proposed change to a law in the Knesset. To read how, click here.