This opinion piece from @RabbiAviShafran won first place in Journalistic Excellence in Covering Zionism, Aliyah, and Israel. https://t.co/OIlXz0sr9N

— JTA | Jewish news (@JTAnews) June 29, 2021

Category Archives: Personalities

Parshas Pinchas – Perfect Timing

How despondent Pinchas could have easily felt when his grandfather, father and uncles, and all their future descendants, were chosen by Hashem to be cohanim (Shemos, 28:1). He himself, having been born before that moment, was not among that role’s grantees.

He probably did not mind, though. Because his subsequent action (at the end of parshas Balak), the killing of Zimri and Cozbi, could only be a proper act – and Hashem confirmed its propriety – if it had been committed by an utterly selfless person. One needs a sense of self to feel slighted.

How ironic, though, is the fact that, had Pinchas actually been a cohein at the time of his violent act, the act, justified though it was, would have rendered him unable to serve in that special role. Because a cohein who has killed a person, even properly or accidentally, is disqualified to serve as a cohein.

Hashem made Pinchas a cohein only after – in fact, because – of his act (Zevachim 101b). Pinchas’s ultimate status as a cohein, in the end, depended on his having been “left out” when his relatives were granted that status.

Few of us are truly selfless, and many of us are easily slighted. When we are, we do well to recall Pinchas’ experience. The Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 230:5) actually states as halacha that “One should be accustomed to say: All that Hashem does is for the best.”

Sometimes we are fortunate, as Pinchas was, to live to see how that is true.

But even when we don’t, it still is.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

An Antisemite’s Perceptive, Worthy Words

Most people, if they are familiar with the name at all, associate “Chateaubriand” with a meat dish. But François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand was a famous French author who died in 1848. He was not well disposed toward Jews, considering them cursed for the farcical sin of deicide, and wrote approvingly about how “Humanity has put the Jewish race in quarantine.”

And yet, some other words of his are, even coming from so poisoned a pen, more than worthy for Jewish pondering during the annual period of the “Three Weeks” just begun, during which Jews mourn the destruction of the Holy Temples in Jerusalem and the Jewish exile. I am indebted to the late British Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks for, in his Haggada, bringing Chateaubriand’s words to my attention.

The French writer visited a desolated Jerusalem, where he saw Jews pining for the arrival of mashiach and the end of the Jewish exile.

And wrote as follows:

“This people has seen Jerusalem destroyed seventeen times, yet there exists nothing in the world which can discourage it or prevent it from raising its eyes to Zion. He who beholds the Jews dispersed over the face of the earth, in keeping with the Word of God, lingers and marvels. But he will be struck with amazement, as at a miracle, who finds them still in Jerusalem and perceives even, who in law and justice are the masters of Judea, to exist as slaves and strangers in their own land; how despite all abuses they await the King who is to deliver them… If there is anything among the nations of the world marked with the stamp of the miraculous, this, in our opinion, is that miracle.”

And a further miracle, may it come swiftly and in our days, will be the arrival of that king, and the end of our exile.

(c) 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Parshas Balak – Invitation to Murder

Were a donkey to suddenly develop the power of speech and address me, I would, I’m quite sure, be flabbergasted.

Faced with just such an asinine address, though, Bil’am isn’t struck silent and doesn’t collapse in shock. In fact, he seems entirely unfazed, and simply reacts to his donkey’s protest — “What have I done to you that you struck me these three times?” — by responding “Because you mocked me!” (Bamidbar 22:28-29).

What occurs to me as a possible explanation of his nonchalance is that he had become so oblivious to the difference between animals and humans — and indeed related to his beast as a partner in life — that the shock factor simply wasn’t there. True, the donkey had never spoken before, but maybe the animal simply hadn’t had anything to say until then.

The view of man as a mere fur-less ape is evident, too, at the end of the parsha, where the idolatry of Ba’al Pe’or celebrates the base physical functions that humans and lower creatures share in common.

The idea that humans are a mere subset of the animal kingdom has been taken by celebrated “ethicist” Peter Singer to its logical conclusion. Human infants, he has said, are “neither rational nor self-conscious,” and so, “The life of a newborn is of less value than the life of a pig, a dog or a chimpanzee.”

Equating humans and animals, which is common in our times as well as in ancient ones, isn’t just a means of legitimating debauchery.

It is nothing less, when truly internalized, than a prelude to murder.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

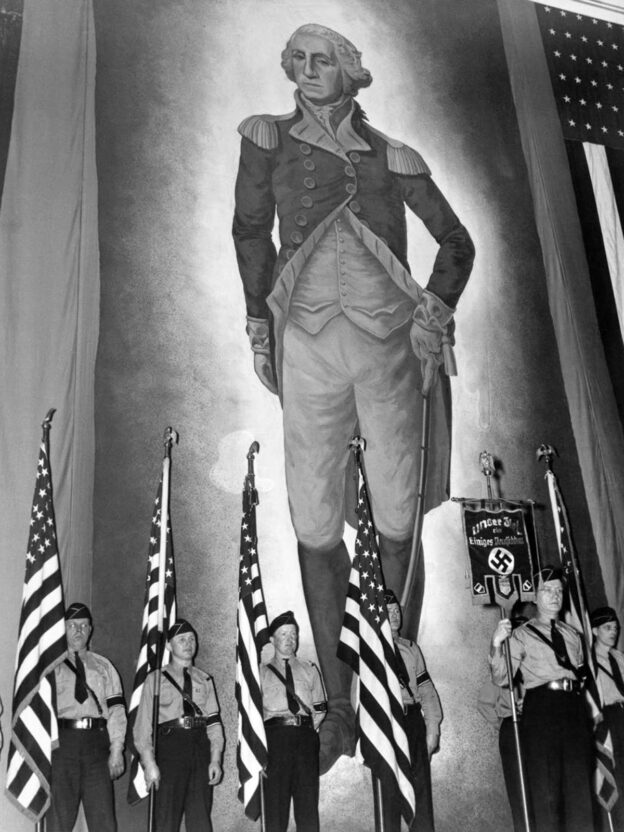

Desecrations of the American Flag

A piece I wrote about the misuse of the American flag was published by NBC-THINK on Flag Day, earlier this week. It can be read here.

Chagrined by AOC’s Reaction

I have defended Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on a number of occasions in several public venues. But I was chagrined by her reaction to the recent Hamas/Israel war, and express why here.

Parshas Korach – Humility: The Mark of Leadership

Few contrasts are as striking as the one between Moshe, the “most humble of all men,” who had to be drafted by Hashem to lead the Jewish people, and Korach, who was consumed with a desire for a leadership role.

And, like deceitful populists over ensuing millennia, Korach insisted that he was merely standing up for the masses, advocating for their democratic rights. Who needs a mezuzah (i.e. a leader) if the house is filled with holy books (i.e. the magnificent masses)?

Many contemporary leaders, some more shamelessly than others, advanced their aspirations in Korach-fashion, lusting for power while claiming to be championing the people. (A rare exception was Dwight Eisenhower, the only American president who had to be drafted to run for that office.)

In the authentic Jewish religious world, true leaders are always drafted — that is to say, “elected” not by campaigns and misleading claims but rather by unsought public acclaim. I have been privileged to have spent time in the vicinities of several, and was deeply affected by their selflessness and modesty. My rebbe, Rav Yaakov Weinberg, was one; see https://www.rabbiavishafran.com/mr-to-us/. His yahrtzeit is Shiva Asar B’Tamuz.

And, just like Moshe was accused of sins he didn’t commit, so are Gedolim today sometimes attacked for imagined misdeeds. And not only by people lacking any relationship to Torah, but even some who are meticulously observant.

Ohn ben Peles, the Midrash recounts, a confederate of Korach’s, was saved from the latter’s fate by Mrs. Ohn. After plying her husband with enough wine to put him to sleep, she sat outside their tent and uncovered her hair. So when Korach’s supporters came to fetch her husband and saw the immodest woman, religious folks that they were, they turned on their righteous heels and left.

Even religious people can fall victim to would-be-dictators’ lies.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Galus and Gastronomy

Some people, like pollster James Zogby, see Israeli offerings of hummus and babaganoush as a form of “cultural genocide.” And cookbook author Reem Kassis says that the marketing of hummus as an Israeli food makes her feel that she doesn’t exist.

I can’t say whether hummus was originally an Arab or Israeli delicacy, only that I enjoy it with a bit of olive oil and paprika on a pita. But I have what to say about Jewish cuisine and what it teaches us. You can read what here.

Yetzias Kaufering

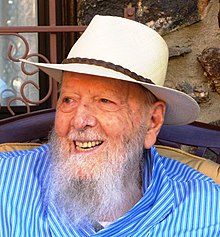

Pesach Sheni is a special day in my family, because in 1945, on that day of the Jewish calendar, my father-in-law, who passed away earlier this year, was liberated from Dachau by American soldiers.

You can read about his last days in the concentration camp, and about his family’s marking of that day each year, here.

(Photo is of my father-in-law and one of his orphan charges in France.)

Two Jews Walk Into a Palm Springs Shul

A piece I wrote for Forward about my late father-in-law’s friendship with the celebrated novelist Herman Wouk — whose second yahrtzeit was last Shabbos — can be read here.