After disembarking from the SS Ernie Pyle, the transport ship that brought World War II refugees from Europe to the United States in the late 1940s, my father used the $75 dollars provided him by the social service Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society to buy a pair of tefillin.

Those are the small black leather boxes containing verses from the Torah that observant Jewish men don on their arms and head daily. The pair he had with him, from his bar mitzvah in the shtetl, had not fared well over the war years.

Simcha Bunim Szafranowicz was in his early 20s when he arrived, and had spent the war years, first, as a young teen, fleeing the Nazis when they invaded his native Poland; and later, after being captured in Russian-controlled territory, banished along with a group of his fellow yeshiva friends and their teacher to a work camp in Siberia.

For many years, he didn’t speak about his wartime experiences to his three children, I being the middle one. When we became adults, we urged him to recount the experiences of his own young adulthood.

Once our father began to share his recollections, they came out in a torrent.

He told us about how, when the Nazis invaded Poland and his entire town fled the approaching troops, he, a 14-year-old, and his fellow shtetl-folk, were captured in a nearby town where they had sought refuge. The group of refugees was crowded and locked in a synagogue. Then, nearby houses were set aflame. The boy, like the others, expected to die there.

But they were saved, at the last moment, incredibly, by a passing Nazi officer, who berated the soldiers who had acted without orders. My father and the others suspected the officer was Elijah the prophet in disguise.

Shortly thereafter, he told us, the “stubborn boy,” as our father described his younger self, took leave of his parents – whom he would never see again – to board a train to a city with a yeshiva. He had always wanted to study in one.

But the yeshiva he managed to get to, in Vilna, Lithuania, was overtaken by the Russians, and its Polish students and faculty were given a choice: become Russian citizens or be banished, as foreign nationals, to a work camp in Siberia.

They chose the latter. After a weeks-long, packed cattle-car train journey to the far east of the continent, he and his fellow yeshiva boys and their teacher were put to work chopping down trees in temperatures that reached 40 degrees below zero. Once he became seriously ill there and almost died.

After the war, he and the others made their way to the Soviet sector of Berlin, from which they were smuggled to the American section — during which dangerous trip my father was shot in the upper arm. He showed us the scar, which we had never noticed before.

The boys and their teacher re-established their yeshiva in an Austrian city called Salzburg, where they prayed and studied until they could find ways to leave the blood-soaked soil of Europe for faraway lands like Palestine or the U.S.

My father managed to contact a distant relative in America, who sponsored his immigration to the country he would come to cherish. He shortened his surname and met our mother, who had arrived from Poland herself but before the war. Their dates in New York consisted of riding the subway together, and his singing Hebrew and Yiddish songs – he had a keen sense of music and a sweet voice – for her.

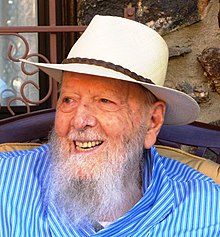

The couple moved to Baltimore and my father, with my mother’s tutoring him in English (which he mastered perfectly), eventually became the beloved rabbi of an Orthodox congregation that he ended up serving for more than a half century. To make ends meet, he attended the University of Baltimore and received a degree in accounting, which served him well as he juggled his synagogue duties, his family and his job as an auditor for the city.

There are stories galore I can tell about the impact he made as a rabbi on countless Jewish men and women, boys and girls. Not to mention about the veneration he came to receive from his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren — and countless people who just happened to cross paths with him.

He was called to heaven six years ago, when he was 91. As he breathed his last breaths in my brother’s home, where he had been living for a number of months, he mustered the energy to quietly ask the family members around him for something. It wasn’t clear what.

But my sister-in-law deciphered his request and told my brother, who took my father’s tefillin and placed them lovingly on our father’s arm and head.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran