When the Torah (Shemos, 12:26) recounts the question the Haggadah attributes to the “wicked son,” it states that, when our ancestors heard it, they responded by bowing down in thanksgiving. What were they thankful for?

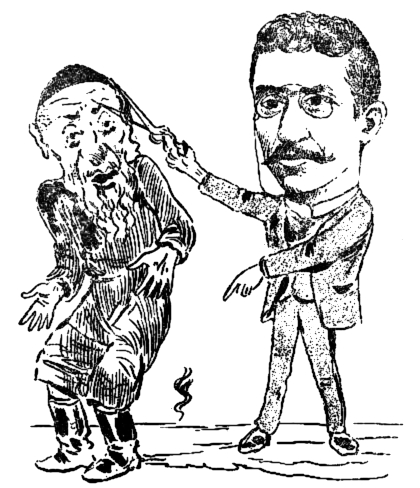

The Sheim MiShmuel, quoted in Eliyhu Ki Tov’s Haggadah, explains that the very fact that the Torah considers the ben rasha to be part of Klal Yisroel, someone who merits a response, was the reason for the Jews’ happiness.

When, in other words, we were a mere extended family of individuals, each member stood or fell on his own merits. And many individuals, sadly, did not merit to leave Mitzrayim.

After Yetzias Mitzrayim, however, even a “wicked son” is considered a full member of the Jewish People. The revelation of that truth demonstrated to our ancestors that something had radically changed since their pre-Egypt and Egypt days. The descendants of Yaakov had become something new, a nation.

In the Haggadah, we are told, regarding the “wicked son,” hakhei es shinav,” usually translated as “set his teeth on edge.” He has, we are told, been kofar ba’ikar, denied something essential (literally, “rejected a root”). Had he been in ancient Egypt, we tell him, he would not have been among those saved by Hashem.

A cognate of hakhei, however, exists in the Gemara (Kesuvos 61a), which notes that foods that have kiyuha, an enticing sharpness of smell, must be offered to the waiter serving them.

Might the Haggadah’s hakhei carry a similar meaning? That we are meant to entice the wicked son to join us, by telling him that had he been there – in ancient Egypt – he would not have escaped. But he is now here, post-Yetzias Mitzrayim, and thus part of Klal Yisrael, willy-nilly.

And the “something essential” that he seems, by his question, to deny may refer not to some theological “root,” but rather to his own root, planted deeply, whether he realizes it or not, within our people.

And so our response may hold our hope that his hearing and comprehending that fact will bring him to accept his status as a Jew, and to change his ways.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran