It’s all too easy to disassociate the beginning of a parsha from the end of the preceding one. But Rav Shlomo Yosef Zevin, in LaTorah UlaMoadim, sees Hashem’s declaration at the opening of Vo’eira as connected to Moshe’s question toward the end of parshas Shemos. That question was (Shemos 5:22) “Why have You treated this nation badly?” And Elokim’s response (6:2) is “I am Hashem.”

Rav Zevin compares the apparent question/answer disconnect here with what transpires in Ki Sisa, when Moshe asks Hashem to “Let me know Your ways” (33:13) and is responded to with “You will see My back but My front will be unseen” (33:23).

What gives?

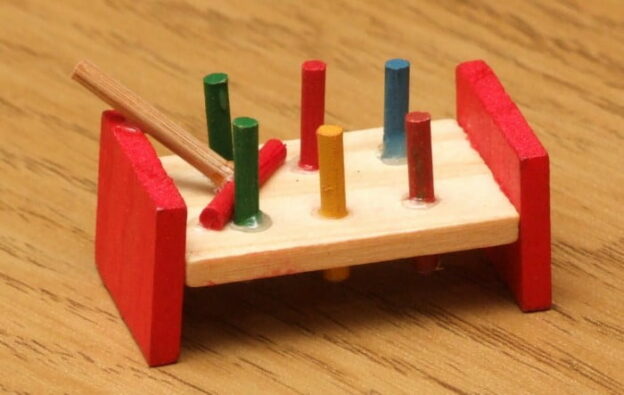

In both cases, explains Rav Zevin, the response expresses the reality that we cannot perceive justice, or even any sort of sense, with our limited purview of history. We are like a person first seeing the “burial” of a wheat kernel and its decay in the ground without having ever seen the stalk of wheat that emerges as a result, and the loaf of bread to which it will eventually contribute.

Elokim – the midas hadin, strict justice, name of Hashem – tells Moshe to rest assured that the din he perceives is not detached from “I am Hashem” – the sheim havaya that implies rachamim, benevolence. The din is but a prelude to rachamim, and the redemption of the Jews is at hand.

And the ultimate redemption, too, as hard as it may be to spy, is forthcoming no less.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran