The Jewish credo, “the Shema,” declares Moshe’s directive to love Hashem “with all your heart, with all your soul and with all your resources” (Devarim 6:5).

And, famously, Chazal understand “all your soul” as meaning even if being faithful to Hashem means dying as a result (Berachos 54a).

That command has been honored over the millennia in countless acts of Jewish martyrdom at the hands of enemies who sought to force their victims to violate one of the precepts for which a Jew is to die rather than transgress, or in times when such evildoers sought to uproot Torah observance from Jewish people.

Martyrdom is the ultimate self-abnegation. It is, though, not the only expression of selflessness.

Rabbi Yisrael Salanter noted that the directive to love Hashem with all our souls encompasses not only readiness to lose our entire souls (the ultimate negation of self) but any overlooking of self-interest in the service of the Divine.

Every situation, in other words, whereby “negation” of one’s self serves a higher purpose.

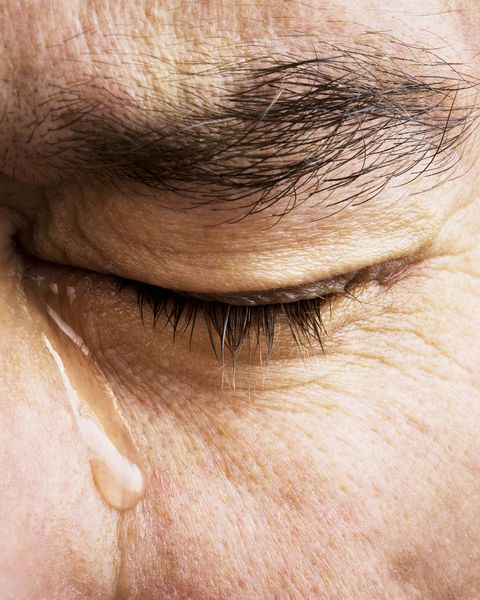

It happens often that one is faced with a situation that violates one’s sense of self, or self-image. It might be a slight, or an open insult; a usurping of a turn or an unwarranted deprivation.

If such situations are not legally actionable (like suffering a financial loss or damage due to another’s misdeed), it is commendable to recognize that it is only one’s “self” that has been put at stake, and that “dying” a little — overlooking the slight — is not only proper but an actual act of Kiddush Hashem, a mini-martyrdom.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran