I’m not entirely sure why eyepatches are often associated with dangerous characters like pirates. But the only character in the Torah who is described as having a single eye is Bilaam (Bamidbar 24:3, although, according to Rashi, his missing eye was unpatched).

The significance of that physical trait is the subject of considerable commentary, much of it focused (forgive me) on two eyes representing two ways of seeing things.

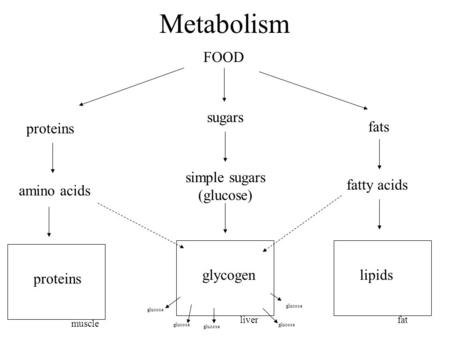

What occurs to me is something else, namely, that having two eyes doesn’t just afford a broader field of vision; it allows us to perceive depth, something beyond the two-dimensional picture we perceive with one eye shut.

That, of course, is because each of our eyes sees a slightly different image (demonstrable by alternating closing each eye while looking at an object; the object shifts), and our brains miraculously combine the two images into a much more informative three-dimensional scene. We see not just a picture but the entirety of the object of our view itself.

Chazal tell us that there are three partners in the conception of every human, a father, a mother and Hashem (Niddah 31a). Bilaam’s monovisioned state, the Gemara, later on the same page, relates, resulted from his disapproving reaction to Hashem’s role during the act of conception:

[Bilaam] said: “Should Hashem who is pure and holy, and whose ministers are pure and holy, peek at this matter?” Immediately his eye was blinded as a divine punishment (ibid).

What was lacking in Bilaam’s purview was an appreciation of the deeper meaning that can be part of a physical act that, if viewed only “two-dimensionally,” or superficially, can seem carnal, even profane. He showed a lack of being able to perceive something beyond the shallow in the physical manifestation of something sublime, a meaningful relationship of love. What he lacked might well be described as depth of vision.

And the result was, in his purely physical life, a physical impediment to seeing anything three-dimensionally.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran