The New York Times has made some progress when it comes to accurately describing what Judaism considers the holiest spot on earth. To read what I mean, click here.

The New York Times has made some progress when it comes to accurately describing what Judaism considers the holiest spot on earth. To read what I mean, click here.

A New York Times article from August 18, 2000, by Laurie Goodstein addressed Senator Lieberman’s religious convictions. It ended with something I said and that Mr. Lieberman repeated on several occasions on the campaign trail. The article is below:

Lieberman Balances Private Faith With Life in the Public Eye

By watching Senator Joseph I. Lieberman carefully, Americans may receive a lesson in the rituals and the realities of living as an Orthodox Jew in America.

Mr. Lieberman attends an Orthodox synagogue, but outside of temple he rarely wears a yarmulke. He eats kosher food and keeps the Sabbath, but unlike many strictly Orthodox men he shakes hands with women. If he could not shake hands, how could he campaign?

Mr. Lieberman refers to himself as an ”observant Jew,” not Orthodox. It is an intentional distinction that his staff laments has been overlooked in all the coverage devoted to the first Jewish politician to run for vice president.

”He refers to himself as observant as opposed to Orthodox because he doesn’t follow the strict Orthodox code and doesn’t want to offend the Orthodox, and his wife feels the same way,” said a Lieberman press officer who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Mr. Lieberman’s aides said they could not make him available for an interview during the Democratic National Convention.

Despite his hesitation to embrace the label, Mr. Lieberman is by practice, heritage and synagogue membership best described as a modern Orthodox Jew. Orthodox Jews try to live according to Halakha, the vast body of Jewish law, and so practice a stricter form of observance than those who belong to the other Jewish denominations — Conservative, the next most traditional, followed by Reform and Reconstructionist. For every prohibition in the Halakha, however, there are exceptions argued over by generations of rabbis.

Mr. Lieberman’s form of observance makes clear that Orthodox Judaism is a continuum that ranges from lenient to stringent interpretation of Jewish law.

”It’s not a denominational difference,” said Rabbi Norman Lamm, president of Yeshiva University. ”It’s individuals who are different. Some individuals within Orthodoxy are more strict than others. But there is a certain amount of wriggle room in Jewish law. There is a degree of flexibility, but the basic commitment must be to the integrity of the law itself.”

Take, for instance, the prohibition on shaking women’s hands, one of many ways in which the Orthodox separate the sexes. The original reasoning was that contact between the sexes should not arouse erotic impulses, rabbis say. Today, in an era when men and women are far less segregated, some Orthodox Jewish men will shake a woman’s hand only if she extends hers first. Some men will extend their hands first, and some will not shake a woman’s hand under any circumstances.

While the Orthodox world is complex, there are two basic distinctions. The ultra-Orthodox, or haredim (meaning ”those who tremble” before God), have traditionally kept an arm’s length from secular society. They include the Hasidic Jews who replanted their Eastern European communities in America, retaining visible signs of their separateness like black hats and side curls.

Modern Orthodoxy, by contrast, tries to integrate the observance of Jewish law with participation in contemporary life.

”Modern means we see it as a religious imperative to engage the modern world, the secular world,” said Rabbi Barry Freundel of Kesher Israel, the temple where Mr. Lieberman worships in Washington, ”and to take that which is of value in that world and make it part of our world.”

Mr. Lieberman was raised in a religiously integrated neighborhood in Stamford, Conn. At home, his family kept kosher and observed the Sabbath. As a high school student, he stayed home from the prom, which fell on the Sabbath, even though he had been voted prom king.

Unlike many Orthodox Jews, he attended public school, not a Jewish day school. He studied the tenets of his faith at Sunday school, at afternoon Hebrew school, and on his own, Mr. Lieberman said in an interview in 1993. He said he left Jewish observance for a time and returned when he became a parent, sending his children to Jewish day schools.

Many of Mr. Lieberman’s most basic religious rituals are intimate acts. He prays three times a day. At morning prayer, Rabbi Freundel said, the senator lays on tefillin, the small leather boxes that contain four biblical passages written on parchment, binding the boxes to one arm and his forehead with leather straps.

He and his wife, Hadassah, keep kosher, adhering to the Jewish dietary laws. They do not mix milk products and meat, and keep separate sets of dishes for each. When he is traveling, aides say, he eats tuna sandwiches, or fruit and vegetables.

Most important, Mr. Lieberman keeps the Fourth Commandment to observe the Sabbath as a day of rest and delight in God’s creation, from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday. Observant Jews are supposed to refrain from writing, using electricity, driving and talking on the telephone.

Mr. Lieberman, with the help of his two rabbis, Rabbi Al Feldman in New Haven as well as Rabbi Freundel, has derived a way to reconcile the requirements of Jewish law with his responsibilities as an elected official. Jewish law teaches that one may break the Sabbath if the matter involves ”concern for human life.” Mr. Lieberman and his rabbis have interpreted that by drawing a line between governing and campaigning. That means he will not break the Sabbath to campaign, but he is required to break the Sabbath to cast a Senate vote or take crucial action on public policy.

In the critical weeks before the Nov. 7 election, Mr. Lieberman has said, he will not campaign on the six days that coincide with the Jewish holiday season. He will instead be in synagogue for Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, which falls on Sept. 30 and Oct. 1, and Yom Kippur, on Oct. 9. The first two days of the Jewish harvest festival, Sukkot, are on Oct. 14 and 15, and Simchat Torah falls on Oct. 22.

Mixed with the pride that many Orthodox Jews have voiced in Mr. Lieberman, there has been some whispering about a few of his and his wife’s omissions. For instance, Hadassah Lieberman does not routinely cover her head with a hat, scarf or wig, standard practice for the married, traditional Orthodox woman who is supposed to dress modestly.

Mr. Lieberman, by going bare-headed outside temple, is not violating Jewish law. But in the last few decades, some Orthodox Jews have come to regard wearing a yarmulke, or kippah, in public as a sign of ethnic pride and identity. Mr. Lieberman has decided not to, Rabbi Freundel said.

”He has never wanted to be the Jewish senator,” the rabbi said. ”He has wanted to be the senator who happened to be Jewish, and wearing the kippah would change the perspective. If you met someone wearing a kippah, the Jewishness is immediately on the table. That is not how he wanted to be known.”

”Safety issues” are another factor, Rabbi Freundel said. Last weekend, just before Mr. Lieberman stepped out of Kesher Israel synagogue in Georgetown after services, a Secret Service agent asked him to remove his yarmulke before walking home, the rabbi said. The yamulke made the senator a ”visible target.”

”There is no question that taking off your yarmulke in the face of danger is permissible,” Rabbi Freundel said.

In interviews, Orthodox leaders said they regard Mr. Lieberman as a worthy representative of Orthodox Judaism, and understand the compromises he has made.

Rabbi Avi Shafran, director of public affairs for Agudath Israel of America, said: ”He’s running for vice president, not chief rabbi. Therefore, there might be some things we would consider not thought out from a religious perspective, but we’re not here to critique his religious life.”

There’s little use carrying on our little charade anymore. We Jews have been exposed. You can read all about it here.

CNN stands accused of endorsing “Israeli propaganda” and censoring “Palestinian perspectives” (note those different, telling nouns.) The New York Times and Washington Post have been similarly criticized. Really.

To read about some of the accusations, and their ludicrousness, click here.

Covered in blood, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is eating a child.

That succinctly describes a cartoon published by a Libyan news organization on this past October 20.

The next month saw a Bahrain news outlet depicting Mr. Netanyahu driving through Gaza in a blood-soaked tank while pulling the Statue of Liberty and President Biden behind him.

Yet another cartoon, featuring a frocked Jew with a large microphone in place of his nose, is captioned: “The Lie of Zionist Media.”

That’s rather like the pot calling the glass of milk black. For decades, Arabic-language newspapers and websites have crawled with anti-Israel and antisemitic images and sentiments. And since the October 7 Hamas massacre, according to the Anti-Defamation League, the ugliness has only increased.

A report from the organization cites examples from Palestinian publications as well as in media based in Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Some also appeared in UK Arabic-language news outlets.

Welcome to the warped world of Arab media.

It’s not only the Arab world’s cartoons that evidence hatred for Jews. What passes for actual news reportage in that realm also regularly promotes incendiary falsehoods, claiming, for instance, that Israel wishes to kill Gazan civilians; and provides ample space to opinion writers whom Goebbels would have been overjoyed to have had on hand.

Among the best examples of such propaganda posing as reportage is Iran’s PressTV, which is nothing more than the malignant mullahs’ mouthpiece. It regularly traffics in Holocaust denial and spreads an assortment of antisemitic conspiracy theories. (Iran isn’t an Arab land, but its rulers share their Arabian coreligionists’ sentiments when it comes to Jews.)

Hezbollah’s Al-Manar television station, based in Lebanon, is another contender. Its director let his less-than-journalistic sentiments show when, speaking about Mr. Netanyahu, he explained that “We want to get close to him, not to interview him, but to kill him.”

And then, of course, we have Qatar’s Al-Jazeera network. It does a good job of pretending to be a neutral, objective medium. But not good enough.

Recently, a laptop belonging to an Al-Jazeera reporter, Muhammad Washah, was found at one of Hamas’ bases in Gaza. It contained photos and intelligence materials linking him to Hamas.

“In the morning a ‘journalist’ on the Al-Jazeera network and in the evening a terrorist in Hamas,” was IDF Lt. Col. Avichay Adraee’s comment on a social media platform.

Apparently, according to Mr. Adraee, Mr. Washah is a senior military operative in Hamas’ anti-tank missile system and has worked in the research and development of aerial weapons for the terror group. Photos show him with rocket-propelled grenade launchers and weaponized drones.

On October 7 itself, it eventually came to light, at least two Al-Jazeera journalists entered Israel with Hamas terrorists and photographed atrocities. Ahmed Najjar accompanied some of the terrorists and filmed several kidnappings. Ismail Abu Omar filmed the Hamas slaughter in Kibbutz Nir Oz, even sharing a video in which he is heard saying: “The comrades have progressed, may Allah bless.”

Sheikh Yusuf Al-Qaradawi, a cleric who praised Hitler, condoned Palestinian suicide bombings against Israeli civilians and appealed for people to “kill Zionists and Jews, down to the very last one…” was, until his death in 2020, a frequent guest on Al-Jazeera’s Arabic channel.

As to moderate Arab voices, Jordan Cope, of the think tank Middle East Forum, asserts that “Other than in Israel… freedom of expression in the Middle East is limited.” There must be some prize for understatement.

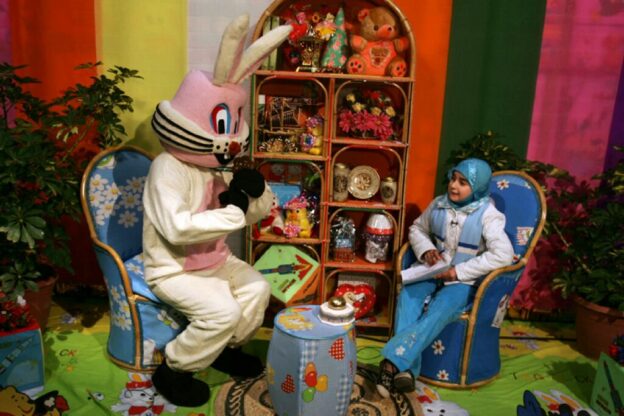

And need we even mention Hamas’ own Al-AqsaTV? Renowned for its children’s programming, a medium in its own right, its broadcasts have featured cute furry characters like “Nahoul,” a giant bee, who encouraged his young fans to “punch” Jews and “turn their faces into tomatoes”; and his co-host, an actual little girl, responded to one of her pint-sized peers who expressed the wish to grow up and “shoot the Jews” – “all of them” – with: “Good!”

When some of the cuddly creatures suddenly disappeared from the program, the kiddies watching were solemnly informed that their beloved friends had been “martyred” by Israelis.

That particular “educational” program aired back in 2014. I find myself wondering if any of the young people who watched it back then might have been, ten years later, in the vicinity of the Gaza Strip’s border with Israel on October 7.

© 2024 Ami Magazine

Black and white is for cookies. Thinking people judge ideas and people by actually evaluating them, not by making thoughtless generalizations.

To read more of what I mean, please click here.

Groucho Marx’s challenge—“Who ya gonna believe, me or your own eyes?”—needs updating in light of some Gaza-war propaganda.

To read about it, please click here.

Good riddance to two New York Times employees. But hold your applause. Why? See here.

To the Editor:

Re “Israel and Hamas Battle in Gaza as Netanyahu Warns of a Long War” (news article, Oct. 9):

Hundreds of Israelis — men, women, children, infants and the elderly — were dragged from their homes by Hamas operatives, and Israeli citizens were murdered in cold blood. Entire families were taken hostage.

Palestinians in Gaza gathered to celebrate the attacks. In the West Bank, residents danced and sang in the streets. In Beirut, children handed out candy to passing motorists and residents set off fireworks.

Whatever one’s opinion about Israel’s policies, those facts and what they say about the country’s enemies should be greatly enlightening.

(Rabbi) Avi Shafran

New York

The writer is the director of public affairs at Agudath Israel of America.

It’s always irksome when news media report one side of a story without making the effort to see if there may be (as there always is) another side. This tends to happen quite often when the story is about religious Jews.

To read about a recent such example of journalistic malpractice (and an older one), click here.