Across an ocean but hot on the heels of Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s not-so-subtle invoking of the hoary stereotype of Jews’ wily wielding of wealth – “It’s all about the Benjamins,” she contended, referring to $100 bills and pro-Israel influence on Congress – comes an exhibit at London’s Jewish Museum titled “Jews, Money, Myth.”

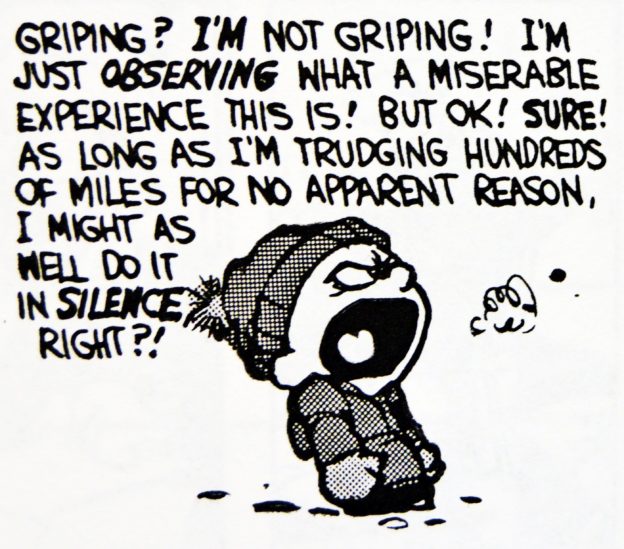

It features, well, a wealth of anti-Semitic imagery, from an 1807 British board game called “Game of the Jew” to a money-dispensing figurine of an Orthodox Jew sold last year in Poland. Other awful offerings include the opening sentences from a Nazi-era children’s book. “Money is the god of the Jew,” the Teutonic tykes were tutored. “He commits the greatest crimes to earn money. He won’t rest until he can sit on a great sack of money.” And a helpful cartoon of that image ensures that the lesson was learned.

Greed, of course, is a pan-human phenomenon. But if any lives are lived in obsession over possessions and the means of acquiring them, it’s those of the typical westerner, craving cars, music, jewelry, clothing and high-tech toys. Most Orthodox Jews – who are those usually depicted in the ugly imagery – have always had more rarified priorities in life.

And yet it is the Jew who is accused of obsession with money. Jewish success born of business acumen and, more importantly, divine blessing has for centuries been twisted into the ugly trope that Jews are more prone to greed and malfeasance than other groups of humanity.

We aren’t, of course, but since when has anti-Semitism ever been linked to logic?

There’s an “on the other hand,” though, here. Because there is a kernel of truth to the charge that we believing Jews have a special relationship with money.

Rabi Elazar informs us (Chulin 91a) that Yaakov Avinu was dangerously “left alone” at Nachal Yabok because he crossed back over the river to retrieve some pachim ketanim, small jars. A lesson to us, the Tanna explains, that “the property of the righteous is dearer to them than their bodies.”

That comment is not meant to counsel miserliness; it conveys an important Jewish thought: Every penny has true worth, for it can be turned into something meaningful. We might think of someone who rinses out and re-uses foam cups as some sort of miser; and maybe he is. But the cups might also be his pachim ketanim, and he might also be a righteous man, reluctant to waste something usable. If he’s generous to the needy, we know which one he is.

And so, while stinginess is ugly, frugality is not. It is a meaningful Jewish trait.

Money’s worth is not only a function of what Rabi Elazar observes elsewhere, that “Each and every penny contributes to a large sum” (Bava Basra, 9b), but because there is inherent value in every thing. As Rabi Yitzchak reveals (ibid), “One who gives a penny to a poor person is blessed with six brachos.” Pretty good deal.

Money, moreover, offers us opportunities for honesty. A believing Jew carefully keeps an accounting of his assets and obligations – including his debts and charitable responsibilities.

And cash can yield great Kiddush Hashem as well.

My wife and I had the pleasure several weeks ago of spending a Shabbos in the lovely community of Scottsdale, Arizona, as guests of the local shul, Ahavas Torah, and its esteemed Rav, Rabbi Ariel Shoshan.

We stayed in the home of a Rebbi at the Torah Day School of Phoenix, Rabbi Noach Muroff, and his wife and family. Back in 2013, the Muroffs lived in Connecticut and Rabbi Muroff, an unassuming, modest person, found himself the subject of incredulous reports in international media. He had purchased a desk and discovered $98,000 that had fallen into the back of the piece of furniture. (During our stay, I wrote a Hamodia column on the desk!)

He decided to return the money to its owner, and a Gadol to whom he confided the story told him that it was an opportunity for a Kiddush Hashem that shouldn’t be squandered. And so a member of the media was apprised of the happening, and the rest was, as they say, history.

Many might have counseled the Muroffs to just keep the windfall. After all, they had bought the desk “as is.” But farther-seeing eyes counseled otherwise. And the world saw a true picture of how a Jewish-minded Jew looks at money, as a valuable means, not a meaningless end.

He may have forfeited a large sum, but, actually, he got a really great deal.

© 2019 Hamodia