Some racial or national stereotypes are outright falsehoods. Mexicans may take siestas (as do many Israelis) during the hottest time of the day, but all the workers from south of the border whom I’ve observed have been exceedingly industrious and hard-working.

Other stereotypes are exaggerations, not fabrications. I think some stereotypes of Jews fall into that category. Some of the mockeries aimed at us may in fact have their origin in high ideals. Penny-pinching, for instance, is just a derisive way to refer to frugality; and frugality bespeaks an appreciation for the worth of every single resource with which Hashem has gifted us.

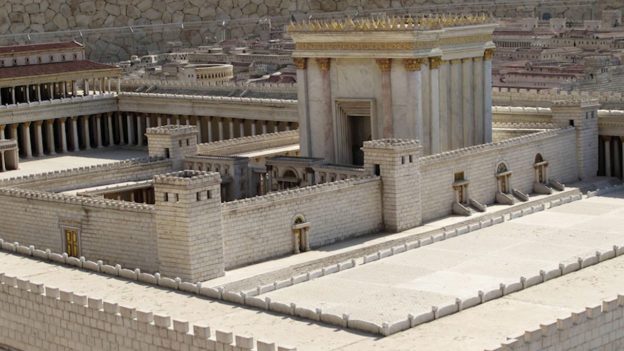

The Torah forbids the wasting of material or money. “Each and every penny,” Rabi Elazar is famously quoted as saying, “adds up to a fortune” (Bava Basra 9b). And fortunes, we all know, can be put to effective, ideally charitable, use. So, while “penny-pinching” can certainly refer to meaningless, selfish hoarding, it can also be the result of a wise recognition that wasting any resource debases it, and us.

Likewise the stereotype of Jews as worriers. Senior citizens reading this may have memories of telegrams (for you young’uns: they were messages sent instantaneously over distances, like e-mails, but for which one had to pay for each letter of each word). The old Jewish joke had it that a Jewish fellow’s telegram to his family far away read: “Start worrying. Details to follow.”

The Jewish worry-wart stereotype, though, may well have its roots in a deep Jewish truth: there is in fact much about which to worry.

That has always been the case, of course. Whether war or other violence, disease or accident, myriad threats have abounded, and continue to abound. Today, though, we are, or should be, particularly sensitive to all sorts of newer things that can harm us. Cars, guns, terrorists, serial killers and… invisible enemies.

Abba Binyamin (Berachos 6a) describes some such potential dangers as sheidim, demons, and informs us that “If the eye only had the ability to see them, no creature could endure” their sheer multitude.

Most of us aren’t sensitive to the presence of sheidim these days. But we certainly are to microbes – noxious bacteria, viruses and fungi – that are everywhere, and whose onslaughts we only survive because of the workings of our immune systems.

To which we generally give nary a thought. Only when our natural biological defenses malfunction do we – suddenly panic-stricken – recognize how fortunate we had been all that time when things went well.

Our mesorah admonishes us to give that thought constant attention. And no less attention to all the other myriad unseen dangers we face. In Modim, we acknowledge “all the wonders and favors that are with us daily, evening and morning and afternoon.”

From the first words a Jew recites upon arising, thanking our Creator for “returning my soul to me with kindness” – our breathing, after all, proceeded all night apace despite the oblivion of our sleep hours – to the brachah of Asher Yatzar, acknowledging the disasters that would follow were our digestive or circulatory systems hampered – we are guided to be keenly sensitive to the potential disasters that face us continuously.

Thus, the Jewish mandate to recognize always what could go wrong in our lives yields a meaningful disquietude. Which informs the worrier stereotype.

The same readers who remember telegrams might remember, too, the long-ago cartoon character “Mr. Magoo,” whose signature trait was sight-impairment (the caricature would never be acceptable these rightly disability-sensitive days).

Bald, big-nosed and behatted, Mr. Magoo’s comicality stemmed from his constant mistaking of objects for entirely other objects (and occasionally people), and from his encounters with an assortment of life-threatening circumstances, which always ended happily, without the protagonist’s awareness that he had ever been in danger in the first place.

He might be happily driving a car off a cliff overlooking a lake and land on a ship’s deck, only to just drive off the gangplank as the ship docked, to motor along on his merry way, never realizing he had ever left the road.

We’re not really so different. We, too, don’t fully appreciate how every day from which we emerge relatively unscathed was a day during which Hashem protected us from threats of which we weren’t even aware. So, worry away. It’s a very Jewish thing to do. It means we recognize what dangers are out there and, hopefully, to quote Modim again, the nissim shebchol yom imanu, the “miracles that are daily with us.”

The “velt” around us in the U.S. will soon be commemorating a secular holiday that really isn’t so secular at all. Thanksgiving’s religious roots really can’t be denied. Whom, after all, is being thanked?

President George Washington made it abundantly clear when, in 1789, proclaiming the first nationwide Thanksgiving celebration, he characterized it “as a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favours of Almighty G-d.”

Klal Yisrael has in many ways positively influenced the larger world. The first American president’s words well reflect that fact.

But our recognition of the signal favors of Hashem is a daily, indeed constant, one.

© 2019 Rabbi Avi Shafran