You’ve no doubt heard the term “October Surprise.” But have you heard of a “Tishrei Surprise”? Yes, it’s a thing. As you can read here.

You’ve no doubt heard the term “October Surprise.” But have you heard of a “Tishrei Surprise”? Yes, it’s a thing. As you can read here.

The Gemara (Shabbos 88a) quotes “a certain Galilean” as having said “Blessed is the Merciful One, Who gave a three-fold Torah [in the broad sense, Torah, Neviim and Ksuvim] to a three-fold nation [Cohanim, Levi’im and Yisraelim] by means of a third-born [Moshe] on the third day [of separation of men and women] in the third month [Sivan].”

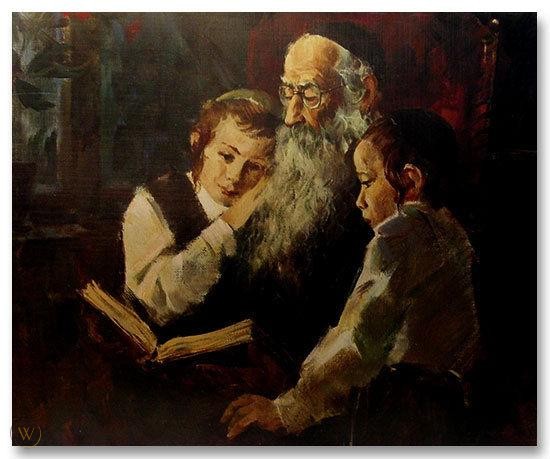

The stress on threes concerning the giving of the Torah, it occurs to me, reflects the essence of mesorah itself, its transmittal. Just as the most elemental physical chain needs three links, so, too, the conceptual one. Each of us is a middle link; we must have received the mesorah and then transmitted it. And our recipients then become middle links themselves.

In parshas Haazinu, we read, similarly: “Ask your father and he will tell you, your grandfather and he will say to you” Devarim 32:7). The threesome chain again.

And, intriguingly, the word employed for the father’s telling is “viyagedcha”, from the root lihagid — which Rashi elsewhere (Shemos 19:3) says implies harshness; and for the grandfather’s telling, the word is viyomru – whose root, omer, Rashi (ibid) characterizes as a “soft” communication.

The Torah may mean to teach here that a father must be an authority figure, and his transmittal of the mesorah more demanding, while a grandfather’s guidance is to be, well, grandfatherly, imparted with a more gentle touch.

(c) 2020 Rabbi Avi Shafran

[photo by Esky Cook]

Rosh Hashanah is the only holiday on the Jewish calendar occuring at the new moon, beginning on a night when the moon isn’t visible at all. That fact is hinted at in the posuk “Tik’u bachodesh shofar bakeseh liyom chageinu” (“Sound the shofar on the New Moon, at the appointed time for the day of our festival”) — Tehillim 81:4. The word bakeseh, “at the appointed time,” can be read to mean “covered.”

The moon is, famously, a symbol of Klal Yisrael. It receives its light from the sun, as we receive our enlightenment from Hashem; it wanes but waxes again, as we do throughout history; and it is the basis of our calendar.

Various ideas lie in the oddity of Rosh Hashanah being moonless. One that occurred to me has to do with that latter connection, that the moon is our marker of time, our clock, so to speak. When we repent of a sin, Chazal teach, the sin can be erased from our past — even, if our teshuvah is complete and sincere, turned into a merit!

And so, we are particularly able on Rosh Hashanah, the beginning of the ten days of teshuvah, to undermine time, to go back into the past and change it.

What better symbol of that power than to remove our “clock” from the sky?

Ksiva vachasima tovah!

The Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni) at the start of parshas Nitzavim sees in the parsha’s opening words, “You are standing today” the message that, despite the sins and travails of Klal Yisrael up to that point, and the klalos enumerated in parshas Ki Savo, the nation is still standing. Indeed, the Midrash continues, “the curses stand you up [ma’amidos eschem].” In other words, they strengthen you.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that physical systems naturally degenerate into more and more disordered states.

Living systems, though, seem to act otherwise. A domeim, a non-living item like a rock or mineral, is indeed entirely subject to entropy. A tzomei’ach, though, a plant, which grows, less so. And an animal, a chai, even less so, as it can also move around to promote its wellbeing.

And a human is even more able to defend against entropy, manipulating his environment, using intelligence, tools and creativity to protect himself.

The highest rung on the hierarchy, according to sefarim, is Yisrael. Perhaps we are entropy-resistant, too, in a special way — in the ability to turn challenges that would naturally wear away other people, leaving them feeling dejected and hopeless, into not just perseverance but renewed strength. Haklalos ma’amidos eschem.

The Churbanos of the Batei Mikdash, for example, were followed with determined and successful Jewish renewal, as was the most recent churban, that of Jewish Europe. Parts of Klal Yisrael have returned to Eretz Yisrael, and Torah study and practice thrive throughout the world.

And in our personal lives, too, as Rav Dessler writes, our failings and fallings can, through our pain and teshuvah, become fuel for our determination to reach even greater heights.

A timely thought during these waning days of Elul.

The very first Rashi in the Torah, quoting a Midrash, indicates the importance of Bikkurim, the first fruits offering that opens parshas Ki Savo. Bikkurim is one of the “raishis” concepts that the word Beraishis (understood as “for the sake of something called raishis) refers to.

And Bikkurim, as evident from the words that are spoken when they are brought, is an expression of “hakaras hatov,” a truly fundamental Torah concept that is usually, though, not entirely accurately, thought of as “gratitude.”

In truth, it is something more subtle and sublime, indicated in a direct translation of the phrase: “recognition of the good.” That is why an example of the concept, as per the Gemara (Bava Kamma, 92b) is the commandment that “You shall not abhor an Egyptian, because you were a stranger in his land,” in last week’s parsha. And why the maxim expressing it is “Don’t throw a clod of dirt into a well from which you drank” (ibid).

So even someone who intended you nothing good, even an inanimate object, deserves hakaras hatov. How does that work?

My understanding is that the recognition, while expressed to a person, people or object, is ultimately to Hashem, for causing the good – in the case of the Egyptian slavery, the “purification” (kur habarzel) needed to prepare Klal Yisrael to receive the Torah; in the case of the well, its appearance when one was thirsty. The action of hakaras hatov is through the Egyptians and through the well but its ultimate expression is to Hashem.

I remember having negative feelings when on rare occasions I would see a certain person who in effect once forced me to leave a job and community I loved. But then, pondering how what resulted in the end was in fact a tremendous brachah for me and my family, I realized that I needed to feel hakaras hatov toward him. Well, toward him, which I indeed came to feel, but as a means to truly recognizing the good that Hashem had bestowed.

Some recent reading led me to wonder if there might be something about German soil that somehow resonates, in susceptible people, with cruelty and murder? Might the Nazi slogan “Blut und Boden!”—“Blood and Soil!”—hold deeper meaning than mere nationalist dedication to the land?

To read my thoughts on the matter, please visit:

https://www.amimagazine.org/2020/08/12/blood-and-soil/

This is the first of a series of short thoughts I hope, with Hashem’s help, to offer pretty much weekly about the parshas hashavua or yamim tovim, in the hope that they might be deemed worthy of discussion at Shabbos or Yomtov tables

On a superficial level, there is something disturbing about the ritual of egla arufah, which will be read from the Torah this Shabbos, parshas Shoftim.

The ritual, is commanded in a case where the body of a murder victim, presumably a wayfarer, is found between cities. The procedure, which involves the elders of the nearest city dispatching a calf, is called a kapparah, an atonement, yet there seems to be no sin for which the elders need atone. That’s because part of the ritual is their sincere declaration that they did everything they could to ensure the safety of the visitor during his visit, including supplying him with his needs before he left.

And it certainly isn’t atonement for the killer; if he is ever discovered, he faces a murder charge and its penalty.

So whom is the atonement for?

It seems clear to me that it is for Klal Yisrael.

Rav Dessler, in Michtav Me’Eliyohu, teaches that the concept of arvus, the “interdependence of all Jews” implies that when a Jew does something good, it reflects the entire Jewish people’s goodness. And the converse, too.

Thus, when Achan, one man, misappropriated spoils after the first battle of Yehoshua’s conquest of Canaan, the siege of Yericho, it is described as the sin of the entire people (Yehoshua, 7:1). Explains Rav Dessler: Had the people as a whole been sufficiently sensitive to Hashem’s commandment to shun the city’s spoils, Achan would never have been able to commit his sin.

So it may be that in the case of the murdered wayfarer, too, even if no particular person was directly responsible for the murder, what could have enabled so terrible an act to happen might have been a “critical mass” of lesser offenses, perhaps things that Chazal likened to murder, such as causing another Jew great embarrassment or indirectly causing a person’s life to be shortened.

In which case, the atonement would be for Klal Yisrael as a whole, interconnected as all its members are.

The idea, in truth, inheres in the very words to be recited by the elders. After they declare their lack of any personal involvement in the murder, they plead with Hashem to “atone for your people Yisrael…”

And the Baal HaTurim’s comment on that phrase makes the idea explicit: “From here we see,” he writes, “that all members of Klal Yisrael are interdependent.”

The unhealthy confusion of Torah values with politics brings disrepute to Torah and harm to Torah Jews.

No party platform can substitute for our mesorah.

As a community, we ought to clearly and proudly stand up for the Torah’s stance on societal issues, embracing a worldview that identifies with no party or political orientation. Our interests may dovetail with a particular party or politician in one or another situation, but our values must remain those of Sinai, not Washington.

Moral degradation infects a broad swath of the American political spectrum. In the camps of both liberals and conservatives, many political players are on a hyper-partisan quest for victory at all costs.

Good character and benevolent governance are devalued, contrition is seen as weakness and humility is confused with humiliation. Many politicians and media figures revel in dividing rather than uniting the citizens of our country. Others legitimize conspiracy theories. None of this is good for America, and certainly not for us Jews.

Shameless dissembling and personal indecency acted out in public before the entire country are, in the end, no less morally corrosive than the embrace of abortion-on-demand or the normalization of same-gender relationships. The integrity and impact of what we convey to our children and students about kedusha, tzni’us, emes, kavod habriyos and middos tovos are rendered hollow when contradicted by our admiration for, or even absence of revulsion at, politicians and media figures whose words and deeds stand opposed to what we Jews are called upon to embrace and exemplify.

These are not new problems. But the challenge seems to grow worse with time. If we don’t stop to seriously consider the negative impact of our community’s unhealthy relationship with the current political style, we risk further erosion of our ability to live lives dedicated to truly Jewish ideals.

We Jews are charged to be an example for all Americans.

Serious moral issues — truth, loyalty, contrition, vengeance, tolerance — are at the heart of much of today’s political discourse. Whether we realize it or not, many of us have come to be guided in such matters, at least in part, by politicians and media figures with whom we share neither values nor worldview.

We are a people charged with modeling and teaching ethical behavior and morality to others. It should be inconceivable for us to be, and be seen as, willing disciples of deeply flawed people who are now the de facto arbiters of what is morally acceptable. We should be ashamed when Torah leaders seem to have been replaced as our ethical guides by people of low character and alien values.

As Orthodox Jews, we live in a benevolent host society to which we have rightly given our loyalty. It is thus important that we not be regarded by the American public as turning a blind eye to the degradation of our moral climate in exchange for political support for parochial interests.

We must not allow ourselves to be co-opted by any party.

There are issues of great importance to us, like education funding, anti-discrimination laws and the affordability and safety of our neighborhoods, and we rightly advocate for our positions.

But we must reject the efforts of those who, for self-serving electoral gain, seek to turn Jews against any party or faction. Our practical focus should be on recruiting allies and building alliances, and we ought to shun partisan posturing that only alienates us from those who govern us.

We must ensure that Israel is not used as a political weapon.

We must oppose efforts to turn support for Israel from a broad consensus into a wedge issue. Although we may rightly be concerned about trends regarding Israel in some corners, indicting an entire party as anti-Israel is not only inaccurate but has the potential of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. Nor should any party’s strong support for Israel become a justification to blindly support its politicians in every other matter. We should advocate for Israel’s security and other needs without painting ourselves into a partisan corner.

We should vote as Jews, not partisans.

Nothing stated above is intended to address anyone’s voting choices. We write simply to caution against the reflexive identification of Orthodox communal interests with any particular party or political philosophy.

To that end, let us commit to being guided only by Torah perspectives and strive to insulate ourselves, our families, students and congregants from being influenced by the objectionable speech and conduct that have come to infect many parts of the political spectrum.

When we vote, let us do so as Torah Jews, with deliberation and seriousness, not as part of any partisan bandwagon. We are not inherently Democrats or Republicans, conservatives or liberals. We are Jews – in the voting booth no less than in our homes – who are committed, in the end, only to Torah.

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman

Rabbi Hillel Goldberg

Jeff Jacoby

Eytan Kobre

Yosef Rapaport

Rabbi Avi Shafran

Dr. Aviva Weisbord

An article I wrote for Forward on the targeting of statues of Confederate leaders and slave owners can be read here.