What an abrupt transition, from the miracles and wonders of the earlier parshios of Sefer Shemos to this week’s list of prosaic, painstaking laws.

But, just as every letter in the Torah is necessary for it to be kosher, so are life’s seeming banal interactions, in reality, opportunities for holiness. When we conduct our personal and business lives properly, not as rote or out of a self-generated sense of right or wrong but in fulfillment of Hashem’s commands, that is no different from the mitzvos that recall kri’as Yam Suf.

Anshei kodesh, “people of holiness” (Shemos 22:30), is our divine prescription. The Kotzker Rebbe is said to have remarked that “Hashem has more than enough angels; He wants people of holiness.” He wants our humdrum human lives to be infused with holiness.

A corollary of that thought lies in the realm of Hashem’s hashgacha, which covers our every experience. Not only when it’s readily evident, in seemingly “miraculous” happenings, but no less in our “mundane” lives.

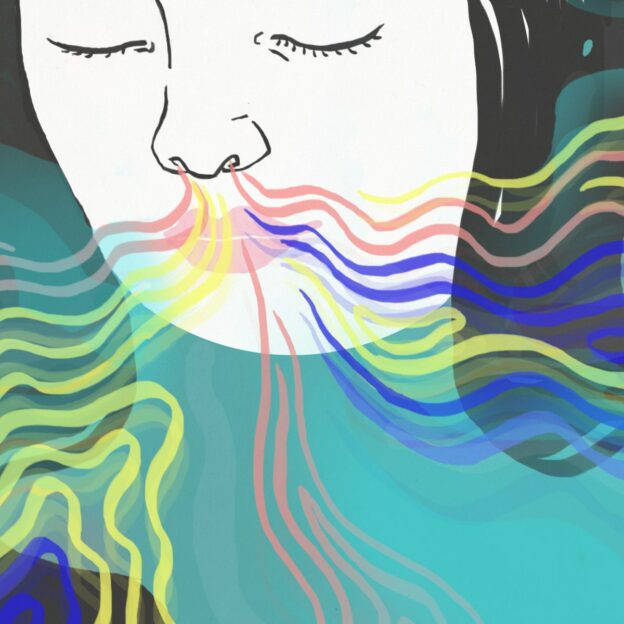

A friend of one of our daughters once shared a powerful story with her, about a woman scheduled to fly to a distant city for an important job interview. The lady found herself stuck in unexpected traffic and arrived at the airport in barely enough time to park her car. She ran to the check-in counter, only to discover that she had missed her flight by mere seconds, and that there were no others that would get her to her interview on time. Dejected, she headed home.

Several hours later, the plane on which she was to have flown began its descent to its destination, the woman’s reserved seat empty… As the plane descended, there was some turbulence, and the captain told the passengers to make sure their seat belts were securely fastened…

And then, the plane… touched down, safely. The passengers disembarked. End of story.

The lady never discovered any reason for having lost the chance of the job, and ended up taking a less lucrative one in her home city.

But there was a reason.

Whether we perceive it or not, there always is.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran