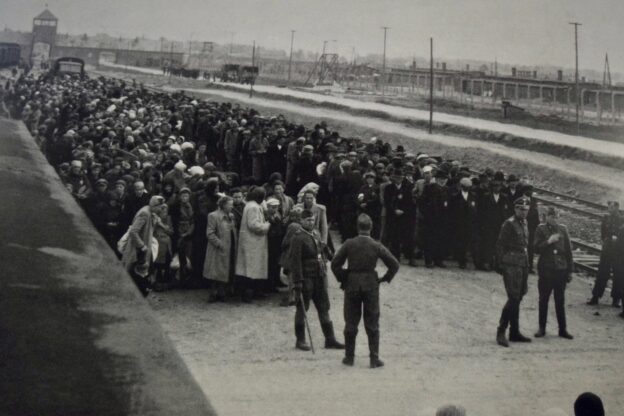

It may have started back in the summer of 2020, when a Kansas Republican county chairman posted a caricature of the state’s Democratic governor Laura Kelly on his newspaper’s Facebook page. Ms. Kelly had issued a public-setting mask mandate, and was depicted wearing a mask with a Magen David on it. In the background was a photograph of European Jews being loaded onto train cars. The caption: “Lockdown Laura says: Put on your mask … and step on to the cattle car.”

The next summer, we were treated to Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene’s criticism of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s mask requirement for the chamber, in which Ms. Taylor Greene declared: “You know, we can look back at a time in history where people were told to wear a gold star… were put in trains and taken to gas chambers in Nazi Germany. And this is exactly the type of abuse that Nancy Pelosi is talking about.” Under pressure from her peers, the congresswoman later apologized; but her point, such as it was, had been made, and likely energized her like-minded supporters.

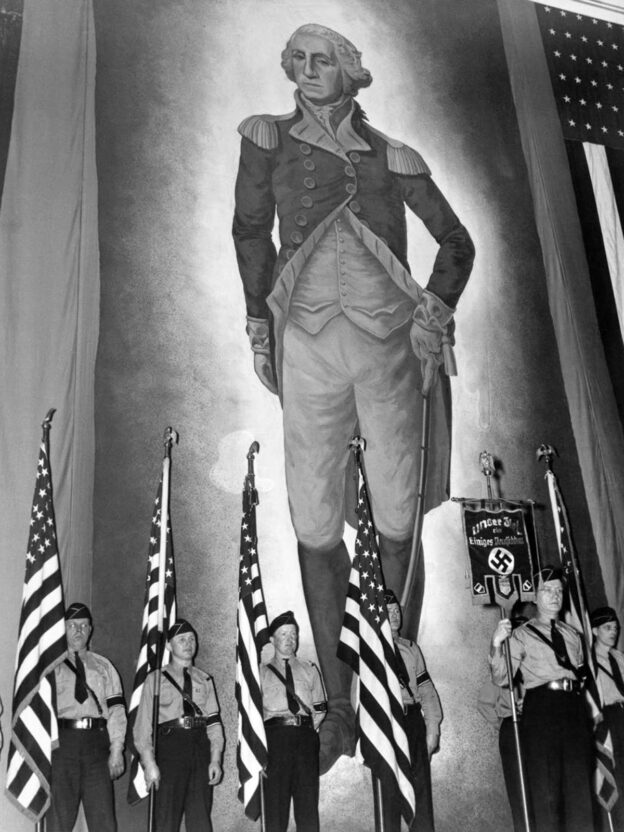

Then came Oklahoma GOP chairman John Bennett’s comparison of private companies requiring employees to get vaccines to — three guesses — the Nazis’ forcing Jews to wear a yellow star.

The odious comparisons just seemed to pile up, across the country. They were getting attention, after all, and attention is catnip for political felines. Of course, the offensive comments, each in turn, were all roundly condemned by Jewish groups. Wash, rinse and repeat.

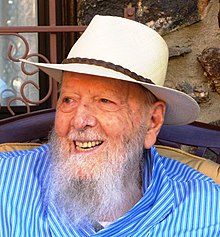

Last week, though, may have offered us the Mother Of All Such Slurs, when broadcaster Lara Logan, once a respected CBS News foreign correspondent and now a Fox Nation commentator, appeared on the “Fox News Primetime” program, where she addressed Dr. Anthony Fauci’s recommendation that Americans get fully vaccinated, including booster shots, in the wake of the appearance of the Omicron COVID variant. Her words:

“This is what people say to me, that he doesn’t represent science to them. He represents Joseph Mengele, the Nazi doctor who did experiments on Jews during the Second World War and in the concentration camps. And I am talking about people all across the world are saying this.”

A cursory search turns up no one but Ms. Logan saying such a thing, but maybe those people all across the world spoke with her privately.

As usual, Jewish groups rightly rushed to condemn her statement. But she was impervious to the criticism, later re-tweeting to her 197,000 Twitter followers a Jewish fan’s comment: “Shame on the Auschwitz Museum for shaming Lara Logan for sharing that Jews like me believe Fauci is a modern day Mengele.” Well, that makes two people, anyway.

This introduction shouldn’t be, and probably isn’t, necessary, but for any readers not fully familiar with Josef Mengele, yimach shemo vizichro: He was a Nazi doctor given the title “Todesengel” — German for malach hamaves. At Auschwitz, he performed deadly experiments on prisoners, selected victims to be killed in the gas chambers and helped administer the Zyklon B, or hydrogen cyanide, gas.

Mengele was particularly interested in twins, separating them on their arrival at the concentration camp, and performing experiments on them, including infecting them with germs to give them life-threatening diseases, performing operations on them without anesthetics and killing many of them to compare their and their siblings’ internal organs.

As to Dr. Fauci’s sin, it is being cautious — overly so, to his critics — about public health measures.

Aside from the insult and offensiveness of the Holocaust comparisons, the repeated use of the murder of six million Jews as a political tool should bother us for another reason:

With each one, even dutifully followed by condemnations, the memory of Churban Europa is further dulled a bit, the force of its historical reality subtly blunted. The public mind is, slur by slur, lulled into regarding the Holocaust as a mere metaphor. That may be of no concern to the offenders, but it should be to us.

Because the cascade of casual co-optings of the Holocaust to score political points dovetails grievously with the diminishing number of living links to the events of 1939-1945.

And all the loathsome little Holocaust deniers and revisionists are just licking their lips as they wait in the wings.

© 2021 Ami Magazine