The thought experiment begins by asking us to ponder a world where the dead routinely rise from their graves but in which no grain or vegetation has ever grown. Long departed relatives routinely reappear and, presumably, funerals are au revoirs, not goodbyes. Food is procured exclusively from non-vegetative sources.

And the fantasy continues with the sudden appearance of a stranger who procures a seed, something never seen before in this bizarre universe, and plants it in the ground. The inhabitants look on curiously, regarding the act as no different from burying a stone, but are shocked when, several days later, a sprout pierces the soil where the seed had been consigned. They are even more flabbergasted to witness its eventual development into a full-fledged plant, bearing fruit – and, even more astonishing – seeds of its own.

Rav Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler painted the bizarre panorama, and, as it happens, the conjured scenario has pertinence to Chanukah.

The point Rav Dessler was making was the fundamental idea that there really is no inherent, objective difference between what we call nature and what we call miraculous. We simply use the former word to refer to that to which we are well accustomed; and the latter, for things that we have never before experienced. All there is, in the end, Rav Dessler concludes, is Hashem’s will, expressed most commonly in nature.

Yesh chachma bagoyim, “there is wisdom among the nations.” The celebrated essayist and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson famously conveyed much the very same idea, when he wrote:

“If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore; and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God which had been shown! But every night come out these envoys of beauty, and light the universe with their admonishing smile.”

The star-filled sky, Emerson asked us to realize, is seen as non-miraculous only –only – because it appears every night.

Famed physicist Paul Davies put the thought starkly and strikingly: “The very notion of physical law,” he wrote, “is a theological one.”

What does all that have to do with Chanukah?

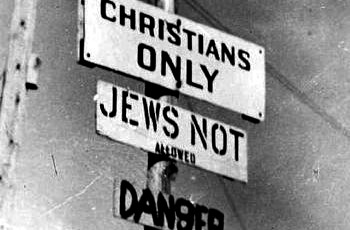

The chag, of course, commemorates the Macabeeim’s routing of the Greek Seleucid fighters who sought to impose heathenism on the Jews in Eretz Yisrael. The Maccabeeim managed to rout their enemy, recover Yerushalayim and rededicate the defiled Beis Hamikdash. Only one vial of tahor, undefiled, oil, though, for use in the menorah was discovered in the debris. It was enough to burn for only one day, yet, once kindled, lasted for a full eight, yielding Chanukah’s observance of eight nights of candle-lighting.

Why, the Beis Yosef famously asked, is Chanukah observed for eight days, when the miracle of the oil was really only evident over seven – since there was sufficient recovered oil for one day?

Many answers have been suggested. One, though, offered by, among others, Rav Dovid Feinstein, zt”l, is based on Rabbi Dessler’s (and Emerson’s, and Professor Davies’) contention.

Seven of Chanukah’s days, goes this approach, indeed commemorate the miracle that the menorah’s flames burned without fuel. The eighth day, though, is a celebration unto itself, commemorating the fact – no less of a miracle to perceptive minds — that oil burns at all. It is an acknowledgment of the Divine essence of nature itself.

Which poignantly echoes the Gemara’s account of how the daughter of Rabi Chanina ben Dosa realized shortly before Shabbos that she had accidentally poured vinegar instead of oil into the Shabbos lamps, and began to panic. Rabi Chanina, who vividly perceived divinity in all and, the Talmud recounts, as a result often merited what most people would call miracles, reassured her. “The One Who commanded oil to burn,” he said, “can command vinegar to burn.”

Which, in that case, is precisely, the Gemara recounts, what happened. Vinegar doesn’t usually burn, of course, unless it’s Rabbi Chanina’s. But the fact that oil burns, for all of us, remains a miracle, if a common one.

Sifrei nistar portray the small Chanukah flames as leaking spiritual enlightenment into the world. Perhaps the realization of the miraculous hidden in the mundane is part of what we are meant to gain from the lights.

Heading into the dismal darkness of what some coarse folks might think of as a “G-d-forsaken” deep winter, the Chanukah lights remind us that nothing, not even nature, is ever forsaken by G-d, nothing devoid of divinity.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran