An oldie about Chanukah that appeared in the New York Times can be read here.

An oldie about Chanukah that appeared in the New York Times can be read here.

I used to pass the fellow each morning as I walked up Broadway in lower Manhattan on my way to work. He would stand at the same spot and hold aloft, for the benefit of all passers-by, one of several poster-board signs he had made. One read “I love you!” Another: “You are wonderful!” The words of the others escape me, but the sentiments were similar.

He looked normal and was decently dressed, and he smiled broadly as he offered his expressions of ardor to all of us rushing to our offices. I never knew what had inspired his mission, but something about it bothered me.

Then one day I put my finger on it. It is ridiculously easy to profess love for all the world, but it is simply not possible. Gushing good will at everyone is offering it in fact to no one at all.

By definition, love must exist within boundaries, and our caring for those close to us is of a different nature than our empathy for others with whom we don’t share our personal lives. What is more, only those who make the effort to love their immediate families and friends have any chance of truly caring, on any level, about others.

Likewise, those with the most well-honed sense of concern for their own communities are the ones best suited to experience true empathy for people outside of their communal worlds.

It’s an appropriate thought for this time of Jewish year, as Sukkos gives way, without a second’s pause, to Shemini Atzeres.

Sukkos, interestingly, includes something of a “universalist” element. In the times of the Beis Hamikdash, the seven days of Sukkos saw a total of seventy parim offered on the mizbeiach, corresponding, says the Gemara, to “the seventy nations of the world.”

The families of people on earth are not written off by our mesorah. A mere four days before Sukkos’s arrival, on Yom Kippur, we read Sefer Yonah. That navi was sent to warn a distant people to repent, saving them from destruction. The Sukkos parim, the Gemara informs us, brought divine blessings down upon all the world’s peoples. Had the ancient Romans known just how greatly they benefited from the merit of karbanos, Chazal teach, they would have placed protective guards around the Beis Hamikdash.

And yet, curiously, Sukkos’s recognition of humanity’s worth is juxtaposed with Shemini Atzeres, which expressed Hashem’s special relationship with Klal Yisroel.

The famous parable:

A king invited his servants to a large feast that lasted a number of days. On the final day of the festivities, the king told the one most beloved to him, “Prepare a small repast for me so that I can enjoy your exclusive company.”

That is Shemini Atzeres, when Hashem “detains” the people He chose to be an example to the rest of mankind, when, after the seventy parim of the preceding seven days, a single par, corresponding to Klal Yisroel, is brought on the mizbeiach.

We Jews are often assailed for our belief that Hashem chose us from among the nations to proclaim His existence and to call on all humankind to recognize our collective immeasurable debt to Him.

And those who are irritated by that message like to characterize the special bond Jews feel for one another as hubris, even as contempt for others.

The very contrary, however, is the truth. The special relationship we Jews have with each other and with HaKodosh Boruch Hu, the relationships we acknowledge in particular on Shemini Atzeres, are what provide us the ability to truly care – not with our mere lips or poster boards – about the rest of the world. They are what allow us to hope – as we declare in Aleinu thrice daily – that, even as we reject the idolatries that have infected the human race over history, one day “all the peoples of the world” will come to join together with us and “pay homage to the glory of Your name.”

© 2022 Ami Magazine

“They are My servants, whom I freed from the land of Egypt” (Vayikra 25:55).

Although the Talmud’s comment on the phrase “They are My servants” – “but not the servants of servants” (Bava Kamma 116b) – has a technical, halachic meaning, it also hints at a broader one.

In other words, not only does it say that a Jew cannot own another Jew, it also signals that Jews are not to indenture themselves to causes other than the Jewish mandate. Not to a political party, social cause or personality. A Jew’s exclusive ultimate role is to be a servant of Hashem.

Because the freedom we were divinely granted from Egyptian bondage was not what many consider “freedom” – libertinism, the loss of all fetters. It was a passage from being “servants to servants” – to Egyptians and Egyptian mores – to becoming servants of Hashem. As Moshe, in Hashem’s name, ordered Pharaoh: “Let my people go so that they may serve Me” (Shemos 9:1).

The Hebrew word for freedom, cherus, the Mishna (Avos, 6:2) notes, can be vowelled to render charus, “etched,” as the Aseres Hadibros were on the luchos. “The only free person,” the Mishna concludes, “is the one immersed in Torah.”

True freedom doesn’t mean being retired and moneyed, lying on a beach with sunshine on one’s face and a cold beer within reach, without a care or beckoning task.

In the words of Iyov, “Man is born to toil” (5:7). True freedom, counterintuitively, comes from hard work. Applying ourselves to a higher purpose liberates us from the limitations of our inner Egypts, and is what can bring true meaning to our lives.

Indian poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore wrote:

“I have on my table a violin string. It is free to move in any direction I like. If I twist one end, it responds; it is free.

“But it is not free to sing. So I take it and fix it into my violin. I bind it, and when it is bound, it is free for the first time to sing.”

A timely metaphor, as we progress from Pesach, the holiday of our release from bondage, to Shavuos, the day we entered servitude to the Divine. And when, like on Pesach, we will sing the words of Hallel.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran

“Second Passover,” or Pesach Sheini, a minor Jewish holiday, is anything but minor in my family. It was on that Jewish date, which, in 1945, fell on April 27 (and this year, falls on May 15), that my late father-in-law, the late Yisroel Yitzchok Cohen, was liberated by American forces from Kaufering, part of the concentration camp complex known as Dachau.

In biblical times, Pesach Sheini, coming a month after Pesach, was a day on which Jews who were unable for various reasons to bring the korban Pesach, or paschal sacrifice, on Pesach had another opportunity to do so, and to eat its meat along with matzos (unleavened bread), and bitter herbs. For my father-in-law, it became a symbol of his own “second chance” — at life. His happy one as a child in the Polish city of Lodz had been rudely interrupted by the Nazis on September 8, 1939.

Mr. Cohen became a teenage inmate of several concentration camps. On Pesach Sheini in 1945, he and a friend, Yossel Carmel, lay in Kaufering, in a corpse-filled pit, where they had been cast by their captors, who thought them dead.

Over recent days, there had been rumors that the camp’s commanders had been ordered to murder all the prisoners, to deprive the advancing Allied armies of living witnesses to their work.

The friends’ fear, though, was leavened by hope, born of the sound of explosions in the distance. “We prayed,” he later wrote, that “the thunderous explosions would go on forever.” The pair, he recalled, “eventually fell asleep to the beautiful sound of the bombs.”

The only moving things in the camp were shuffling, emaciated “musselmen,” the “walking skeletons” who had been rendered senseless by starvation and trauma. And so the pair wondered if, perhaps, the camp guards had abandoned the premises. Alas, though, the S.S. returned, bringing along prisoners from other parts of the camp complex, who were kicked toward waiting wagons and, quite literally, thrown onto them.

But, when no one was looking, the two inmates managed to climb down from where they had been cast and found new refuge in a nearby latrine. “Our stomachs,” he recalled, “were convulsing.”

Eventually the wagons left, and the two young men crept back into their cellblock, posing again, not unconvincingly, as corpses.

Then they smelled smoke. Peeking out from their hiding place, the young men saw flames everywhere. Running outside, the newly resurrected pair saw German soldiers watching a barracks burn, thankfully with their backs toward them. There were piles of true corpses all around, and the two quickly threw themselves on the nearest one that wasn’t aflame.

My future father-in-law thought it was the end, and wanted to recite the “final confession” that Jewish liturgy suggests for one who is dying. But his friend reminded him of an aphorism the Talmud ascribes to Dovid Hamelech, King David, that “Even with a sharp sword against his neck, one should never despair of Divine mercy.”

And that mercy, at least for them, arrived. Every few minutes, bombs whistled overhead, followed by fearsome explosions. The earth shook, but each blast shot shrapnel of hope into their hearts. The Germans now really seemed gone for good.

Dodging the flames and smoldering ruins, the pair ran to the only building still intact, the camp kitchen. There they found a few others who had also successfully hidden from the Nazi mop-up operation.

And they discovered a sack of flour. They mixed it with water, fired up the oven and baked flatbreads. My father-in-law, who, throughout his captivity, had kept careful note of the passing of time on the Jewish calendar, knew it was Pesach Sheini. And the breads became their matzos. No bitter herbs were necessary.

The door flew open and another inmate rushed in breathlessly, finally shouting: “The Americans are here!”

A convoy of jeeps roared through the camp. American soldiers approached the barracks, some, Mr. Cohen recalled, with tears streaming down their faces at the sight of the piles of blackened, smoldering skeletons.

“Along with the American soldiers,” he wrote, “we all wept.”

And then he recited the Jewish blessing of gratitude to God for “having kept us alive and able to reach this day.”

Eventually, Mr. Cohen made his way to France, where he cared for and taught Jewish war orphans; and then to Switzerland, where he met and married my dear mother-in-law, may she be well. The couple emigrated to Toronto and raised five children. For decades thereafter, each Second Passover, he and others who had been liberated from Kaufering that day, along with other camps’ survivors, would arrange a special meal of thanksgivingin Toronto or New York, during which they shared memories and gratitude to God.

As the years progressed, however, sadly but inevitably, fewer and fewer of the survivors were in attendance. And, like his friend Mr. Carmel, Mr. Cohen is no longer with us.

But his wife, and my wife and her siblings, along with scores of grandchildren and great-grandchildren, spread across several states, Canada and Israel, gather in groups, in person or virtually, every Pesach Sheini to recall his ordeals and his liberation, the “second life” we are so grateful he was granted by God.

Many are survivors today, of hateful violence, again against Jews in Israel, as well as other people in places like Sudan, Myanmar, Yemen, Europe and Ukraine. Despair is a natural reaction to witnessing such evil. But those who, like my father-in-law — and my own father, who spent the war years in a Soviet labor camp in Siberia — persevered and created new post-trauma lives show that pasts needn’t cripple futures.

That, like in the case of Pesach Sheini, we can be graced with second chances.

“Propriety” was apparently a theme of the Sadducees, or Tziddukim, one of the camps of Jews during the Second Temple period that rejected the the Torah’s “Oral Law,” the key to understanding the true meaning of the Written one. The former, of course, reveals things like that “An eye for an eye” means monetary compensation, and that “totafos” means what we call tefillin.

And so, the Tziddukim rejected the Oral Law’s direction that “Sabbath” in the phrase “from the day after the Sabbath,” directing the beginning of the Omer-counting period, means the first day of Pesach. They felt, they explained, that having two days in a row of rest and festivity – Shabbos and Shavuos, the fiftieth day of the count – would be a nice and proper thing.

And they advocated, too, a change in the Yom Kippur service described in the parsha, at the very crescendo of the day, when the Kohein Gadol entered the Kodesh Hakadashim. The Oral Law prescribes that the incense offered there be lit only after the Kohen Gadol entered the room. The Tziddukim contended that it be lit beforehand. While they offered Written Law support for their position, their true motivation, the Talmud explains, was the “propriety” of doing things differently.

“Does one bring raw food to a mortal king,” they argued, “and only then cook it before him? No! One brings it in hot and steaming!”

The placing of mortal etiquette – “what seems most appropriate” – above the received truths of the mesorah is the antithesis of Torah, whose foundation is not “you do you” but “you do Me.”

Our very peoplehood was forged by our forebears’ unanimous, unifying declaration at Sinai: “Naaseh v’nishma” — “We will do and we will hear!” – “We will accept the Torah’s laws,” in other words, even amid a lack of ‘hearing,’ or understanding, even if we think we have a better idea.”

“Naaseh v’nishma” stands in stark contrast to society’s fixation on not only having things but having them “our way,” and to Jewish groups that want to bring Torah “in line” with contemporary sensibilities.

But from Avraham Avinu’s “ten trials” to 21st century America, Judaism has never been about comfort, enjoyment or personal fulfillment (though, to be sure, the latter emerges from a holiness-centered life). It has been about Torah and mitzvos – about accepting them not only when they sit well with us but even – in fact, especially – when they don’t.

With apologies to JFK speechwriter Ted Sorenson (Jewish mother’s maiden name: Annis Chaikin), Judaism is not about what we’d like Hakadosh Baruch Hu to do for us, but rather about what we are privileged to do for Him.

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran

It’s intriguing. Three words are used to refer to Yetzias Mitzrayim (yetziah, geirush and shilu’ach; see, for examples, Shemos, 20:2, 11:1 and 8:17).

And they are the very same words used as well to refer to… divorce (see Devarim 24:2, 24:1 and Vayikra 21:7).

The metaphor seemingly hinted at by that fact is that Klal Yisrael became “divorced” from Mitzrayim, to which it had been, in a way, “married,” a reflection of our descent there to the 49th level of spiritual squalor.

But the apparent “divorce” of Klal Yisroel from Mitzrayim is followed by a new metaphorical matrimony. Because that is the pointed imagery of the event that, mere weeks later, followed Yetzias Mitzrayim: ma’amad Har Sinai.

Not only does Rashi relate the Torah’s first description of a betrothal – Rivka’s – to that event (Beraishis 24:22), associating the two bracelets given her by Eliezer on Yitzchok’s behalf as symbols of the two luchos, and their ten geras’ weight to the aseres hadibros. And not only does the navi Hoshea (2:21, 22) describe Mattan Torah in terms of betrothal (vi’airastich li…, familiar to men as the pesukim customarily recited when wrapping tefillin on our fingers – and to women, from actually studying Nevi’im).

But our own chasunos themselves hearken back to Har Sinai: The chuppah, say various seforim hakedoshim, recalls the mountain, which Chazal describe as being held over our ancestors’ heads; the candles traditionally borne by the parents of the chosson and kallah are to remind us of the lightning at the revelation; the breaking of the glass, of the breaking of the luchos.

In fact, the bircas eirusin itself, the essential blessing that accompanies a marriage, seems as well to refer almost explicitly to the revelation at Har Sinai. “Blessed are You, Hashem, … Who betrothed His nation Yisroel through chuppah and kiddushin” – “al yidei” meaning precisely what it always does (“through the means of”) and “mekadesh” meaning “betroth,” rather than “made holy” like “mekadesh haShabbos”).

The metaphor is particularly poignant when one considers the sole reference to divorce in the Torah.

It is in Devarim (24, 2) and mentions divorce only in the context of the prohibition for a [female] divorcee, subsequently remarried, to return to her first husband. The only other “prohibition of return” in the Torah, strikingly, is the one forbidding Jews to return to Mitzrayim (Shmos 14:13, Devorim, 17:16). Like the woman described in Devarim, we cannot return, ever, to our first “husband.”

More striking still is the light thereby shed on the confounding Gemara on the first daf of massechta Sotah.

The Gemara poses a contradiction. One citation has marriage-matches determined by Divine decree, at the conception of each partner; another makes matches dependent on the choices made by the individuals – “lifi ma’asov” – “according to his merits.”

The Gemara’s resolution is that the divine decree determines“first marriages” and the merit-based dynamic refers to second ones.

The implications, if intended as such regarding individuals, are, to say the least, unclear. But the import of the Gemara’s answer on the “national” level – at least in light of the Mitzrayim/Har Sinai marriage-metaphor – provide a startling possibility.

Because Klal Yisroel’s first “marriage,” to Mitzrayim, was indeed divinely decreed, foretold to Avrohom Avinu at the Bris Bein Habesorim (Bereishis 15:13): “For strangers will your children be in a land not theirs, and [its people] will work and afflict them for four hundred years.”

And Klal Yisroel’s “second marriage,” its true and permanent one, was the result of the choice Hashem made – and our ancestors made, by refusing to change their clothing, language and names even when still in the grasp of Mitzri society and culture – and their willingness to follow Moshe into a dangerous desert. And, ultimately, when they said “Na’aseh vinishma,” after which they received their priceless wedding ring under the mountain-chuppah of Har Sinai.

And a fascinating coup de grâce: The Gemara in Sotah referenced above describes the challenge of finding the proper mates. Doing so, says Rabbah bar bar Ḥana in Rabi Yoḥanan’s name, is kasheh k’krias Yam Suf – “as difficult as the splitting of the Sea.”

© 2022 Ami Magazine

Four questions. Four sons. Four expressions of geulah. Four cups of wine. Dam (=44) was placed, in Mitzrayim, on the doorway (deles, “door,” being the technical spelling of the letter daled, whose value is four).

Moving fourward – forgive (fourgive?) me! – Why?

The chachamim who formulated the Haggadah intended it to plant important seeds in the hearts and minds of its readers – especially its younger ones, toward whom the Seder is particularly aimed.

All its “child-friendly” elements are not just to entertain the young people present but more so to subtly plant those seeds. Dayeinu and Chad Gadya and Echad Mi Yodea are not pointless; they are pedagogy.

There are riddles, too, in the Haggadah. Like the Puzzle of the Ubiquitous Fours.

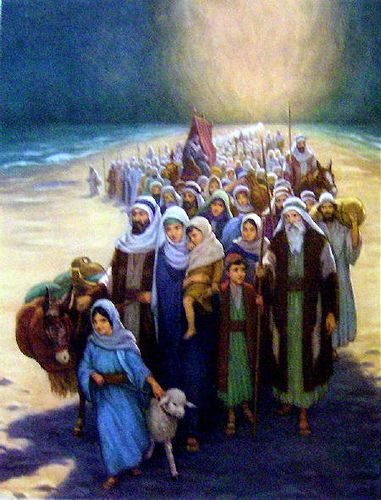

The most basic and urgent concept the Seder experience is meant to impart to young Jews is that Yetzias Mitzrayim forged something vital: our peoplehood. It, in other words, created Klal Yisrael.

Each individual within the multitude of Yaakov Avinu’s descendants in Mitzrayim rose or fell on his or her own merits. And not all of them. Chazal teach us, merited to leave. Those who did, though, were reborn as something new: a people.

And so, at the Seder, we seek to instill in our children the realization that they are not mere individuals but rather parts of a nation unconstrained by geography, linked by history, destiny and Hashem’s love.

Thus, the role we adults play on Pesach night is precise. We are teachers, to be sure, but we are communicating not information but identity. Although the father may conduct the Seder, he is not acting in his normative role as teacher of Torah but rather in something more like a maternal role, as a nurturer of neshamos, an imparter of identity. And thus, in a sense, he is acting in a maternal role.

Because not only are mothers the parents who most effectively mold their children, they are the halachic determinant of Jewish identity. A Jew’s shevet follows the paternal line, but whether one is a member of Klal Yisrael or not depends entirely on maternal status.

The Haggadah may itself contain the solution to the riddle of the fours. It, after all, has its own number-decoder built right in, toward its end, where most books’ resolutions take place. After all the wine, we’re a little hazy once it’s reached, but it’s unmistakably there, in “Echad Mi Yodea” – the Seder-song that provides Jewish number-associations.

“Who knows four?…”

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran

“Existence is by chance and thus meaningless” is Amalek’s credo.

Not only is the opposite true, but seeming “chance” “coincidences” are part of Amalek’s downfall.

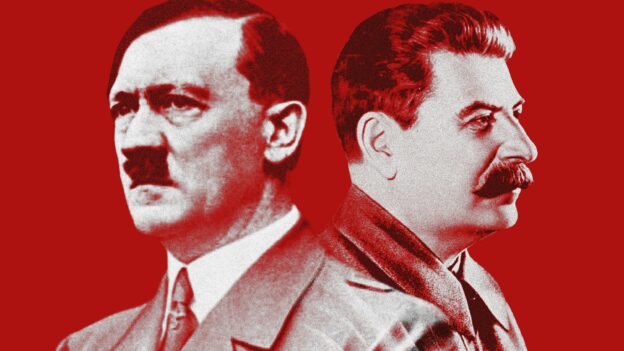

To read about two not-so-long-ago examples of evil’s ends, please see:

https://www.amimagazine.org/2022/03/09/a-tale-of-two-monsters/

Shalach, the root of the word of the parshah’s title, is used elsewhere regarding the exodus from Mitzrayim (e.g. shalach es ami). So are the words yetziah (e.g. Shemos, 20:2) and geirush (e.g. ibid 11:1)

Intriguingly, each of those characterizations of our ancestors’ march from Egypt is also associated with… divorce. Vishilcha mibeiso (Devarim 24:2); viyatz’ah mibeiso (Devarim 24:1); isha gerushah(Vayikra 21:7).

The metaphor telegraphed by that fact is clear. Klal Yisrael was virtually “married” to Mitzrayim, sunken to near its deepest level of tum’ah, and, with Hashem’s help, freed from that “marriage,” divorced, as it were, from Mitzrayim.

The symbolism doesn’t stop there. When the divorce is finalized, Klal Yisrael gets re-married, this time, permanently, to Hashem, with Har Sinai over the people’s heads serving as a chupah. (Indeed, several marriage customs are associated by various sources with Mattan Torah – the chupah, the candles, reminiscent of the lightning), even the breaking of a glass, recalling the sheviras haluchos).

And that would dovetail strikingly with the prohibition against returning to live in Egypt (Devarim 17:16). Because a remarried woman, too, is prohibited from returning to her first husband (Devarim 24:4).

Even more interesting is the implication of the metaphor to the baffling Gemara in Sotah (2a) that asserts that a man’s “initial mate” is divinely decreed before his birth; and his second one, in accord with his behavior.

Because, in our metaphor, Klal Yisrael’s first “mate,” Egypt, was in fact decreed, to Avraham at the bris bein habisarim; and its final one, Hashem, was earned by the people’s behavior: their willingness to follow Moshe into the desert and declaration of naaseh vinishma at Sinai.

And a coup de grâce lies in how the Gemara paraphrased above describes the challenge of finding the proper mates: kasheh k’krias Yam Suf – “as difficult as the splitting of the Sea.”

© 2022 Rabbi Avi Shafran