On June 6, 1944, D-Day, more than 150,000 Allied troops stormed the coast of Normandy to begin the liberation of France from the Nazis.

The criteria for choosing that day included a low but rising tide for the seaborne soldiers, a tide that occurred only around the time of a new or full moon. It took place on the latter.

Other military onslaughts throughout history were scheduled based on the moon’s phase – full moons when light was desired; new moons when darkness was needed to limit soldiers’ visibility to the enemy.

Among the 53 mitzvos in parshas Mishpatim is one that, peripherally, involves the moon. And it is one of the most compelling pieces of evidence of the Torah’s divine origin. Because the mitzvah, by all logic, would seem to doom the Jewish people.

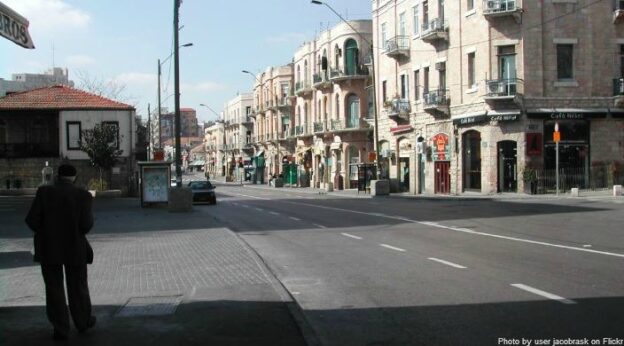

On the shalosh regalim, the three “pilgrimage festivals,” all adult Jewish males are commanded to journey to the Beis Hamikdash in Yerushalayim. That, of course, would leave the borders of Eretz Yisrael essentially open to attack by the Jews’ enemies. And two of those festivals were utterly predictable – because they began on the 15th of their Jewish months, one in the spring (Pesach) and one in autumn (Sukkos). Each at the full moon of its month.

Even the most primitive military strategist would have noticed that pattern and would conclude that the land would be most vulnerable to attack on those holidays. Or, in the summer, during the first quarter moon, when the right half of the moon is lit – the holiday of Shavuos.

Which makes the mitzvah of alyah liregel starkly self-defeating. No human lawmaker would be cruel or dim enough to lay down such a law – only a Legislator who could in fact ensure that the populace would not perish as its result. And, of course, it didn’t.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran