A longform piece I wrote about the Noble Prize laureate physicist I.I. Rabi was published by Tablet, and can be read here.

A longform piece I wrote about the Noble Prize laureate physicist I.I. Rabi was published by Tablet, and can be read here.

I always look forward to feedback on columns, whether the responses are positive or critical. The former keep me writing; the latter help me learn.

On occasion, though, a response is just…well…odious.

Like one that I wrote about in last week’s Ami column, which you can read here.

Last week, President Biden issued a presidential proclamation recognizing the horrific injustice that was the murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old whose brutal killing in Mississippi in 1955 helped galvanize the civil rights movement. A national monument is being created in honor of the murdered boy and his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, who forced the nation to confront the horror of what happened to her son.

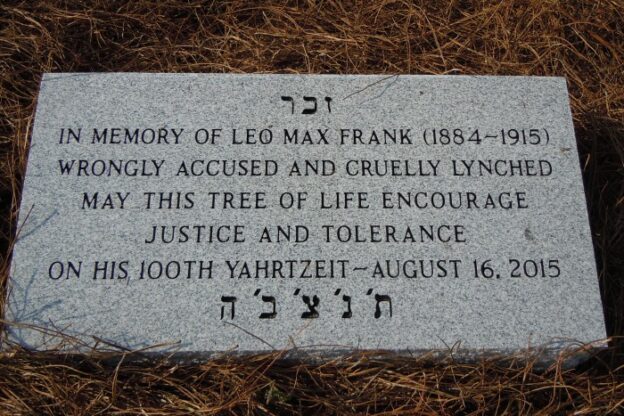

What the revisiting of that evil brought to my mind was another lynching, of a Jewish man in Georgia decades earlier, in 1915. The murder of Leo Frank is a sad part of American history that should not be forgotten.

On April 26, 1913, a 13-year-old girl on her way to Atlanta’s Confederate Memorial Day parade stopped at her place of employment, the National Pencil Company, to collect her paycheck. The next day, she was found murdered in the factory’s basement.

Leo Frank, a 29-year-old Jewish man, was working at the factory that morning and handed the girl her pay. He was the last person to see her and so, when the murder was discovered the next morning, he came under suspicion and was arrested and jailed.

Police, however, had another suspect. Jim Conley, a custodian at the factory, who a witness saw in the factory basement washing out a shirt soaked with what appeared to be blood. Notes, filled with misspellings, were found alongside the murdered girl and Jim Conley was questioned.

After two weeks, he finally admitted writing the notes but said that Leo Frank had asked him to, and had confessed to the murder.

Conley signed contradictory affidavits, which were entered into the trial of Leo Frank. But the glaring inconsistencies were ignored by the jury.

As the trial took place, crowds gathered outside the courthouse chanting “Hang the Jew!”

Based on Conley’s claim and with no real evidence to implicate Frank, the four-week trial ended with a guilty verdict. Outside the courthouse, the crowd cheered the announcement. According to the New-York Tribune, the prosecuting attorney “was lifted to the shoulders of several men and carried more than a hundred feet through the shouting throng.”

The presiding judge, Leonard Roan, sentenced Frank to death by hanging. Appeals ensued for two years. And even after Conley’s former attorney said he believed his former client was the actual murderer, a retrial motion was also rejected.

The case ended up before the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in a 7-2 ruling, allowed Frank’s conviction to stand. Justices Oliver Wendall Holmes and Charles Evan Hughes dissented, stating that the hostility outside the courthouse influenced the conviction.

Georgia Governor John Slaton conducted his own extensive investigation into the case, and, on June 21, 1915, the day before Frank’s execution was to take place, commuted his sentence to life in prison. The governor wrote that “I would rather be plowing in a field than to feel that I had that blood on my hands.”

The community was outraged and Governor Slaton, whose term ended shortly thereafter, fled Georgia with his wife, fearful of the retribution local citizens might visit upon him for keeping the Jew alive.

On August 17, 1915, a mob of 25 men overpowered the guards at the prison farm where Frank was held and kidnapped him. They drove him some 100 miles to a grove near Marietta, handcuffed and hanged him. An approving crowd of some 3000 Georgians, including prominent local citizens, flocked to the lynching site, collecting souvenirs and taking photographs.

Nearly 70 years after the girl’s murder, on March 7, 1982, it was reported that Alonzo Mann, Leo Frank’s office boy, who was fourteen at the time of the killing, said that Conley had murdered the girl, and that he saw the custodian holding her. “If you ever mention this, I’ll kill you,” Conley had told him. Mann said that when he told his mother what he had seen, she told him to keep quiet. He did.

The new evidence led the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles to issue a pardon for Leo Frank – but only based on the state’s failure to protect him while in custody and for not bringing his murderers to justice. It did not, however, exonerate the innocent man.

A jury and judge, after all, had spoken.

© 2023 Ami Magazine

There have been complaints about NYC Mayor Adams’ choice of representatives for his Jewish Advisory Council — to many Orthodox Jews, too few non-Orthodox ones. I make the case for the council as currently comprised, here.

In the wake of Israel’s recent raid on Jenin, various Arab and Islamic countries, playing as they must to their “streets,” registered their condemnation of the operation; the US State Dept. defended Israel’s right to proactively defend herself from terrorism. And members of Congress either joined that judgment or didn’t comment at all.

With one exception. No less repugnant than it was predictable.

You can read about the lone stand-out here.

The evolution of “traditional” lies used over the centuries to persecute, exile and murder Jews into new and, so to speak, improved forms would be amusing were it not so dangerous.

During the years of the Black Death in the late Middle Ages, when death tolls in some towns were as high as 50%, the famously favored scapegoat was “the Jews,” thousands of whom were murdered, many of them burned alive, in the 1300s.

The conspiracy theory back then was that Jews had been poisoning wells in order to kill non-Jews. The theme of Jews as diabolical poisoners was updated in the 20th century by Joseph Stalin in his “Doctors Plot,” in which most of the medical professionals whom he falsely accused of plotting to poison government officials were Jewish. More recent years have seen sundry neo-Nazis accuse Jews of spreading new diseases; and even, more recently, genteel suggestions that polio outbreaks were caused by Jewish anti-vaxers.

Guess what’s back now… Poisoned wells!

“I’m very concerned about my water,” lamented Ms. Grace Clark, of Upper Saddle River, N.J., fearful of what a Jewish cemetery uphill from her home might do to her children. “My kids play” in a nearby brook, she explained, “all the time.”

“We are observing an environmental train wreck in slow motion,” was how Heather Federico of nearby Mahwah chose to characterize that planned final resting place for Orthodox Jews.

I don’t know if either lady was inspired by – or even aware of – the sordid history of blaming Jews for well-tampering.

What I do know, though, thanks to the alacrity of Yeshiva University’s Dr. Moshe Krakowski, is that Ms. Federico and two other concerned citizens quoted in a May 11 story in The New York Times about the Har Shalom Cemetery in Rockland County, N.Y., are regulars on the website of Rise Up Ocean County, the infamous New Jersey group that has been repeatedly called out, even banned for “hate speech” by Facebook, for antisemitic postings. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy denounced the group for “racist and antisemitic statements” and “an explicit goal of preventing Orthodox Jews from moving to Ocean County.”

The Rockland County property at issue, the Times helpfully explains, is, at some 20 acres, “expected to become the largest cemetery in the country reserved solely for ultra-Orthodox Jews.”

Also upsetting some local residents is a mikvah under construction across the street from the cemetery.

Both developments were approved by zoning and planning boards. What they have in common is that they will make life (and death) easier for Orthodox Jews. And help attract them to settle in the area.

That’s not, of course, what the fearful New York and nearby New Jersey residents say is the source of their concern. Their health and wellbeing, they insist, is motivating them.

And indeed, it’s true that cemeteries contribute to ground and groundwater contamination.

Formaldehyde, menthol, phenol, and glycerin are just a few of the toxins that seep into cemetery grounds. Some 800,000 gallons of formaldehyde are placed in the ground each year due to “conventional” burials.

What the word “conventional” refers to, though, are burials that take place after embalming. And that often use caskets made of metals like copper and bronze, which can also leach into the ground. Jewish burials, of course, involve no embalming chemicals and only a simple, safely degradable pine casket. That is what is referred to as “natural” burial, and is entirely kind to the environment.

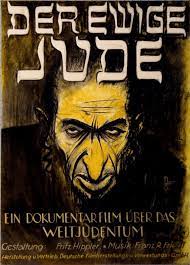

In 1940, the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda released the film Der Ewige Jude, “The Eternal Jew,” which became wildly popular in Germany and throughout occupied Europe. In one famously notorious sequence, it showed hordes of rats, which, the narrator explains, spread disease. “Just,” he continues, “as the Jews do to mankind.”

Popular broadcaster Tucker Carlson, fired in April by Fox News, recently appeared on a social media platform to rail against U.S. support for Ukraine and, in particular, against its Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, whom he called “a persecutor of Christians.” A weird charge, one not even Russian President Putin has made.

Mr. Carlson added his assertion that Mr. Zelenskyy is “rat-like.”

Well poisoning. Jews as rats.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose – “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

© 2023 Ami Magazine

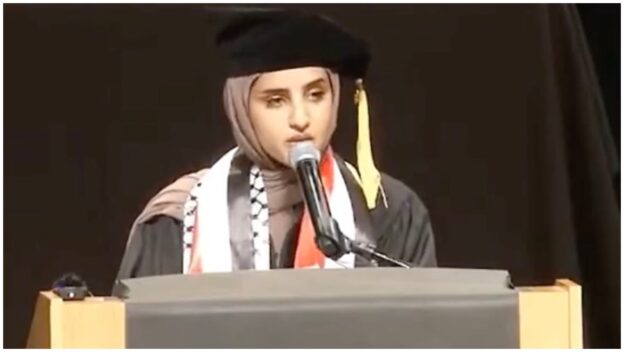

For a great example of sheer, rabid hatred of Israel, lightly disguised antisemitism and the sort of imbecility sometimes born of youth, you couldn’t do better than CUNY School of Law student Fatima Mohammed’s vomitus of venom, in the form of her May 12 commencement speech.

Or, for an example of a well-earned misstep, any better than Palestinian activists’ ill-fated demand that Ms. Mohammed’s diatribe, which had been livestreamed on the school’s YouTube account but then removed, be reposted. Which it was, on the 25th.

The overheated orator praised CUNY Law’s faculty and students for endorsing the BDS movement (that endorsement an ugliness of its own), and accused Israel of “indiscriminately rain[ing] bullets and bombs on worshippers, murdering the old and young, attacking even funerals and graveyards, encouraging lynch mobs to target Palestinians, as it imprisons their children and continues the project of settler colonialism…” And so on. You know the litany of lies.

She also used the occasion of her graduation (as a future lawyer – the thought boggles) to lambaste the New York Police Department and the U.S. military as “fascists”; to allege that “daily, brown and black men are being murdered by the state”; and to defend five leaders of the now-defunct Holy Land Foundation who are serving time for providing material support to Hamas.

“May we rejoice,” she righteously declared, “in the corners of our New York City bedroom apartments and dining tables, may it be fuel for the fight against capitalism, racism, imperialism and Zionism around the world!”

On the 26th, a CUNY representative soberly explained that “Members of the Class of 2023 selected student speakers who offered congratulatory remarks and their own individual perspectives on advocating for social justice. As with all such commencement remarks, they reflect the voices of those individuals.” One had to wonder if the rep would have been as sanguine had the commencement speech attacked blacks or Arabs.

Then came the richly deserved backlash.

New York Congressman Ritchie Torres tweeted: “Imagine being so crazed by hatred for Israel as a Jewish State that you make it the subject of your commencement speech at a law school graduation. Anti-Israel derangement syndrome at work.”

Former New York Republican congressman Lee Zeldin called for CUNY’s taxpayer funding – its 2023 budget amounted to about $ 4.3 billion, most from the state, some from the city – to be revoked “until the administration is overhauled and all Jewish students and faculty are welcome again.”

World Jewish Congress head Ronald Lauder called for the law school’s dean, Sudha Setty, who applauded the ungracious graduate’s speech, to be fired.

New York City Mayor Eric Adams condemned the diatribe, as did New York governor Kathy Hochul and a host of other elected officials.

Eventually, CUNY Chancellor Felix V. Matos Rodriguez and the Board of Trustees issued a statement asserting that, while “free speech is precious…. but hate speech… should not be confused with free speech and has no place on our campuses or in our city, our state or our nation. The remarks by a student-selected speaker at the CUNY Law School graduation, unfortunately, fall into the category of hate speech, as they were a public expression of hate toward people and communities based on their religion, race or political affiliation.”

To be sure, rushing predictably to Ms. Mohammed’s defense were anti-Israel groups, including, sadly, Jewish ones. CUNY Law’s Jewish Law Student Association called the reactions to the hater “pander[ing] to the most cynical reactionaries (ie. @NYCMayor).”

“Jews for Racial & Economic Justice” tweeted that its heroine was being thrown to “the wolves. Utterly shameful.” Well, something was, anyway.

As it happens, with her commencement address, Ms. Mohammed was following in her own muddy footsteps. In a May, 2021 tweet, she expressed her wish that “every Zionist burn in the hottest pit of hell.” And the next day, she referenced the fact that she “pray[s] upon the death of the USA.”

In the wake of the uproar over her repulsive remarks, Ms. Mohammed was reached by a reporter at a relative’s home. She told the journalist, “I do not want to speak to anybody.”

It was a little late for reticence. She had already spoken more than enough, and revealed a thickly sullied soul.

© 2023 Ami Magazine

A renowned news correspondent called a calculated murder a death “in a shootout” and juxtaposed the calculated, willful slaughter of a mother and her two daughters with the unintended death of a Palestinian boy in a crowd that had thrown Molotov cocktails at Israeli soldiers.

You can read about the sadly all-too-typical misreportage here.

As the school year winds down, parents and grandparents of Jewish elementary-age students are treated to… productions!

Things like Siddur and Chumash presentations accompanied by song and verse. There are plays about historical events and uplifting stories. And depictions of Jewish concepts like tefillah or brachos. This grandparent enjoyed a wonderful one last year that was focused on Shmitta and bitachon. (You and your schoolmates were great, Hadassah!)

And then there are the end-of-school-year “Ummah Day” productions at the Muslim American Society Islamic Center in Philadelphia, or “MAS.” They are somewhat different from their Jewish counterparts.

In 2017 and 2019, the children in MAS, as per videos posted on its Facebook page, sang “Chop off their heads!” about their perceived enemies, and expressed their eagerness to become “martyrs” in the cause of liberating “Palestine.” One little girl warbled, “I am a revolution that shakes the occupier. I am a wave on the calm sea. I hold my head high, and I will not be humiliated.”

The 2019 production, a joint venture between MAS Philadelphia and something called the “Leaders Academy,” received some 2 million views. After groups like the invaluable Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) and the ADL, along with some American lawmakers, called attention to the issue, Facebook shut down the school’s page.

Subsequently, MAS Philadelphia and Leaders Academy released a statement expressing sadness over its “mistake” and contending that “antisemitism or other forms of bigotry are foreign concepts to us and we are especially saddened that our beautiful children and community continue to face these accusations [of hating Jews].” The groups pledged to “pave a positive future for our community and increase our work with people from all walks of life.”

Somewhat nonreassuring was the groups’ proud announcement at the time that they had “enlisted CAIR-Philadelphia to help us with a number of [sensitivity] trainings.” CAIR’s national executive director, Nihad Awad, has publicly called Israel a “terrorist state” that targets innocent civilians and declared that Israel “is the biggest threat to world peace and security.”

Which might explain why the sensitivity trainings didn’t work (or, perhaps, depending on the nature of the training, did). Because earlier this month, the little darlings at MAS were at it again.

This time, the children at the school weren’t chopping off heads. But – in a video posted on May 6 by the Leaders Academy and exposed by MEMRI – they celebrated “One Ummah Day” with a song and performance praising “brave” Palestinian girls who support their “real men” as fighters against Israel.

One song describes a girl sending her brother off to battle and telling him: “I will saddle up your horse, and I will tie a dagger to your belt – enhance your resolve.” The video was also posted to the Facebook page of the Alhidaya Islamic Center in Philadelphia, another name for MAS.

Last week, a bill to address the problem of endemic anti-Jewish incitement in Palestinian Authority textbooks was unanimously passed in the United States House Foreign Affairs Committee.

California Democrat Brad Sherman, who introduced the bill, lamented the fact that the PA’s incitement contradicts American values of tolerance and peace, and noted that “For decades, the United States and the American people have been the top donor to the Palestinian people, including to the Palestinian Authority and UNRWA [United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine] – but this is not a blank check.”

“Unfortunately,” he said, “instead of envisioning a Palestinian state alongside Israel, the current Palestinian curriculum erases Israel from maps, refers to Israel only as ‘the enemy,’ and asks children to sacrifice their lives to ‘liberate’ all of the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.”

In April 2021, the Biden administration defended its decision to restore financial aid to the UNRWA with the claim that the United Nations agency was committed to a “zero tolerance” policy regarding antisemitism. Unfortunately, that may have been pleasantly hopeful but it was patently false.

As a report at the time released by the IMPACT-se research institute revealed, schools run by UNRWA continued to teach hatred against Israel.

Incitement against Israel and Jews in Palestinian textbooks is reprehensible.

It’s even more reprehensible in an American school.

And irony is added to reprehensibility when such hatred sets down roots in the City of Brotherly Love.

© 2023 Ami Magazine

Mere hours before a mentally-challenged 30-year-old homeless man shouting at passengers on a New York subway was put in a chokehold by a passenger and died, I was harassed by a man on the Staten Island ferry. My incident ended on a happier note, at least for my harasser.

To read about it, click here.