“The anti-Semitism that is threaded throughout the Republican Party of late goes straight to the feet of Donald Trump.” That, according to Florida Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz, then-chair of the Democratic National Committee. Mr. Trump, she added, has “clearly demonstrated” anti-Semitism “throughout his candidacy.”

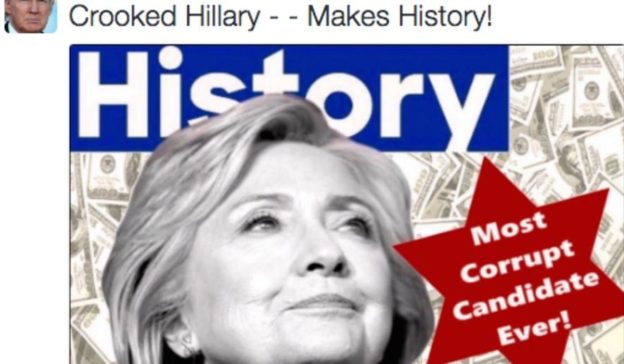

Evidence proffered for the Republican nominee’s alleged Jew-hatred includes the now-famous image disseminated by the Trump campaign, which depicted Hillary Clinton accompanied by mounds of money and a six-pointed star. The image, it turned out, had been borrowed from a white supremacist website.

Then there is the candidate’s speech to a group of Republican Jewish donors in which he said that he didn’t want their money (a sentiment that drew praise from Louis Farrakhan, not otherwise a Trump supporter). And the fact that Mr. Trump has been endorsed by people like David Duke.

More recently, when a Jewish former Governor of Hawaii, Linda Lingle, spoke at the Republican national convention, a torrent of anti-Semitic comments spilled onto the comments section of a livestream of the event. They included praise for Hitler, ym”s, images of yellow stars accompanying the epithet “Make America Jewish Again” and comments like “Ban Jews.”

One needn’t be a supporter of Mr. Trump, though, to recognize that the anti-Semitism charges against him are seriously, forgive me, trumped up. In fact, they’re nonsense.

That he has an Orthodox-converted Jewish daughter and a Jewish son-in-law (and three grandchildren, whom he often refers to as his Jewish progeny), with all of whom he is close, should itself be enough to put the charge to rest.

If more is needed though, well, the Trump Organization’s longtime chief financial officer, Steve Mnuchin, and general counsel, Jason Greenblatt, are both observant Jews. The latter, who has worked for Trump since the mid-1990s, is one of the candidate’s top advisers on Israel and Jewish affairs. And another top Trump adviser has said that Trump backs an Israeli annexation of all or parts of the West Bank. The candidate once received an award from the Jewish National Fund and served as grand marshal of the New York Israel Day parade.

I’m not sure what David Duke or Louis Farrakhan make of all that, but such people, in any event, don’t traffic in facts.

I remind readers that not only does Agudath Israel of America not endorse or publicly support candidates, neither do I as an individual – the role in which I write this column. I am concerned only with what I perceive to be truth and fairness.

Mr. Trump cannot be blamed, either, for support he has received from unsavory corners. He may or may not be happy with haters’ support (politics, after all, being, above all else, about votes). But he has clearly disavowed the sentiments of Duke and company, and can’t be expected to respond each time a malignant mind embraces his candidacy.

Depending on one’s own personal constitution, Mr. Trump may seem refreshing or revolting; his policies, sensible or seditious; his demeanor, exhilarating or unbalanced. But his alleged anti-Semitism is unworthy of anyone’s consideration.

What is, though, worth noting is the aforementioned malevolence, the packs of dogs who hear and respond to imaginary Jew-hate whistles.

As we go about our daily lives, unburdened by the angst and terror that were part of our forbears’ lives over millennia in other lands, it’s easy to imagine that the land of the free is free, too, of Jew-hatred. Then come times, like the current one, when our bubble is burst.

Bethany Mandel is a young, politically conservative, Jewish writer. After she penned criticism of Mr. Trump, a tsunami of spleen spilled forth.

Among what she estimates to be thousands of anti-Semitic messages aimed at her were suggestions like “Die, you deserve to be in an oven,” and depictions of her face superimposed on the body of a Holocaust victim.

“By pushing this into the media, the Jews bring to the public the fact that yes, the majority of Hilary’s [sic] donors are filthy Jew terrorists,” wrote Andrew Anglin in the Daily Stormer, a site named in honor of the notorious tabloid published by Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher, ym”s.

Though it’s disconcerting to perceive, beneath the verdant surface of our fruited plain, some truly foul and slimy things, it’s important, even spiritually healthy, to do so.

Because, amid our protection and our plenty, we are wont to forget that we remain in galus. And that’s a thought we need to think about, especially, the “three weeks” having arrived, this time of Jewish year.

© 2016 Hamodia