I often feel terribly pampered. Especially when I think of my parents’ generation.

At the age when my father, z”l, and several others from the Novardok Yeshiva in Vilna were captured for being Polish bnei yeshivah and banished by the Soviets to Siberia, I was being captured by a teacher for some prank and banished to the principal’s office. When he was trying to avoid working on Shabbos as his taskmasters demanded, I was busy trying to avoid the homework my teachers demanded.

When he was moser nefesh finding opportunities to study Torah while working in the frozen taiga, my mesirus nefesh consisted of getting out of bed early in the morning for davening. Where he struggled to survive, my only struggle was with the mundane challenges of adolescence. Pondering our respective age-tagged challenges has lent me perspective.

And so, while I help prepare the house for Pesach, pausing to rest each year a bit more frequently than the previous one, thoughts of my father’s first Pesach in Siberia arrive in my head.

In his slim memoir, “Fire, Ice, Air,” he describes how Pesach was on the minds of the young men and their Rebbi, Rav Leib Nekritz, zt”l, as soon as they arrived in Siberia in the summer of 1941. While laboring in the fields, they pocketed a few wheat kernels here and there, later placing them in a special bag, which they carefully hid. This was, of course, against the rules and dangerous. But the Communist credo, after all, was “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs,” and so they were really only being good Marxists. They had needs, after all, like matzah shemurah.

Toward the end of the frigid winter, they retrieved their stash and ground the wheat into coarse, dark flour.

They then dismantled a clock and fitted its gears to a whittled piece of wood, fashioning an approximation of the cleated rolling pin traditionally used to perforate matzos to ensure their thorough baking. In the middle of the night, the exiles came together in a hut with an oven, which they fired up for two hours to make it kosher l’Pesach before baking their matzos.

And on Pesach night they fulfilled, to the extent they could, the mitzvah of achilas matzah.

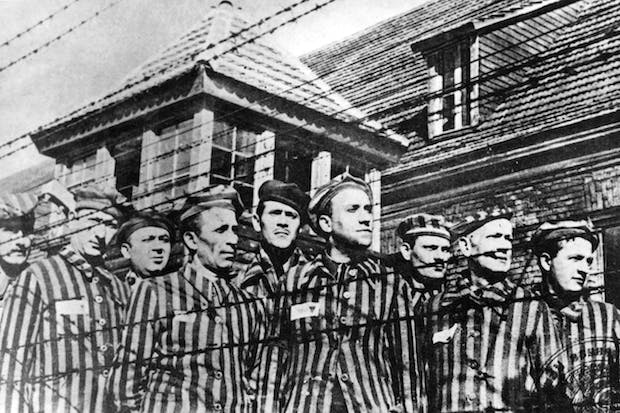

Perspective is provided me too by the wartime Pesach experience of, l’havdil bein chaim l’chaim, my wife’s father, Reb Yisroel Yitzchok Cohen, may he be well. In his own memoir, “Destined to Survive,” he describes how, in the Dachau satellite camp where he was interned, there was no way to procure matzah. All the same, he was determined to have the Pesach he could. In the dark of the barracks on the leil shimurim, he suggested to a friend that they recite parts of the Haggadah they knew by heart.

As they quietly chanted Mah Nishtanah, other inmates protested. “What are you crazy Chassidim doing?” they asked. “Do you have matzos, do you have wine and food for a Seder? Sheer stupidity!”

My shver responded that he and his friend were fulfilling a mitzvah d’Oraysa – and that no one could know if their “Seder” is less meritorious in the eyes of Heaven than those of Jews in places of freedom and plenty.

We in such places can glean much from the Pesachim of those two members – and so many other men and women – of the Jewish “greatest generation.”

A passuk cited in the Haggadah elicited a novel thought from Rav Avrohom, the first Rebbe of Slonim. The Torah commands us to eat matzah on Pesach, “so that you remember the day of your leaving Mitzrayim all the days of your life.”

Commented the Slonimer Rebbe: “When recounting Yetzias Mitzrayim, one should remember, too, ‘all the days’ of his own life – the miracles and wonders that Hashem performed for him throughout…”

Those who, baruch Hashem, emerged from the Holocaust and merited to see children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, naturally do that. But the rest of us, too, have experienced our own “miracles and wonders.” We may not recognize all of the Divine guidance and chassadim with which we were blessed. But that reflects only our obliviousness. At the Seder, when we recount Hakadosh Baruch Hu’s kindnesses to our ancestors, it is a time, too, to look back at our own personal histories and appreciate the personal gifts we’ve been given.

And should that prove a challenge, we might begin by reflecting on what some Jews a bit older than we had to endure not so very long ago.

© 2019 Hamodia