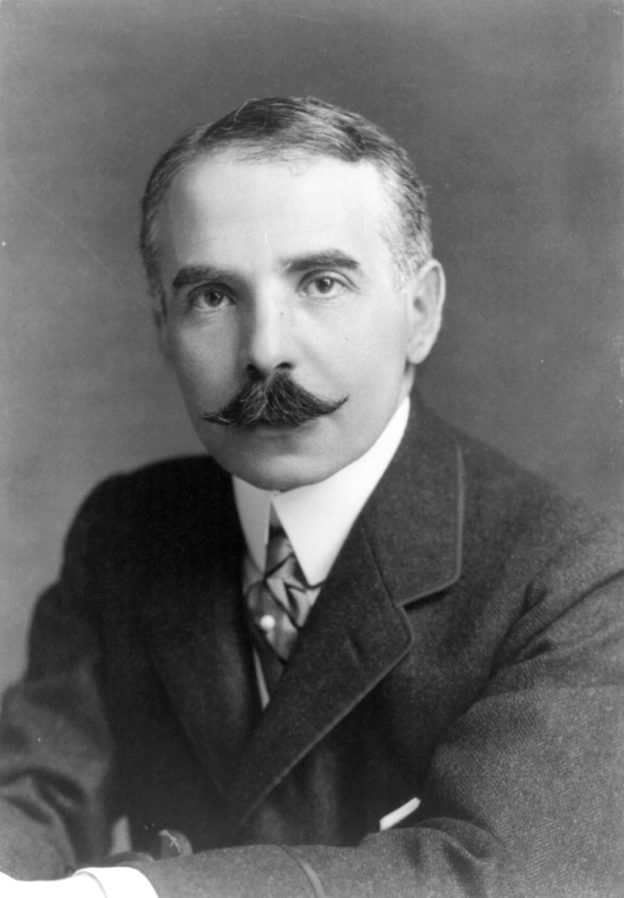

The famous early 20th century German-born American financier Otto Kahn, it is told, was once walking in New York with his friend, the humorist Marshall P. Wilder. They must have made a strange pair, the poised, dapper Mr. Kahn and the bent-over Mr. Wilder, who suffered from a spinal deformity.

As they passed a shul on Fifth Avenue, Kahn, whose ancestry was Jewish but who had received no Jewish chinuch from his parents, turned to Wilder and said, “You know, I used to be a Jew.”

“Really?” said Wilder, straining his neck to look up at his companion. “And I used to be a hunchback.”

The story is in my head because we’re about to recite Kol Nidrei.

Kol Nidrei’s solemnity and power are known well to every Jew who has ever attended shul on the eve of the holiest day on the Jewish calendar. It is a cold soul that doesn’t send a shudder through a body when Kol Nidrei is intoned in its ancient, evocative melody. And yet the words of the tefillah – “modaah” would be more accurate – do not overtly speak to the gravity of the day, the last of Aseres Yemei Teshuvah.

They speak instead to the annulment of nedarim, vows, specifically (according to prevailing Ashkenazi custom) to undermining vows we may inadvertently make in the coming year.

Nedarim, the Torah teaches, have deep power; they truly bind those who utter them. And so, we rightly take pains to avoid not only solemn vows but any declarative statements of intent that could be construed as vows. So, that Yom Kippur would be introduced by a nod to the gravity of neder-making isn’t entirely surprising. But the poignant mournfulness of the moment is harder to understand.

It has been speculated that the somber mood of Kol Nidrei may be a legacy of distant places and times, in which Jews were coerced by social or economic pressures, or worse, to declare affiliations with other religions. The text, in that theory, took on the cast of an anguished renunciation of any such declarations born of duress.

Most of us today face no such pressures. To be sure, missionaries of various types seek to exploit the ignorance of some Jews about their religious heritage. But few if any Jews today feel any compulsion to shed their Jewish identities to live and work in peace.

Still, there are other ways to be unfaithful to one’s essence. Coercion comes in many colors.

We are all compelled, or at least strongly influenced, by any of a number of factors extrinsic to who we really are. We make pacts – unspoken, perhaps, but not unimportant – with an assortment of mastinim: self-centeredness, jealousy, anger, desire, laziness…

Such weaknesses, though, are with us but not of us. The Amora Rav Alexandri, the Gemara teaches (Berachos, 17a), would recite a short tefillah in which, addressing Hashem, he said: “Master of the universe, it is revealed and known to You that our will is to do Your will, and what prevents us? The ‘leaven in the loaf’ [i.e. the yetzer hora] …” What he was saying is that, stripped of the rust we so easily attract, sanded down to our essences, we want to do and be only good.

Might Kol Nidrei carry that message no less? Could its declared disassociation from vows reflect a renunciation of the “vows”, the unfortunate connections, we too often take upon ourselves? If so, it would be no wonder that the recitation moves us so.

Or that it introduces Yom Kippur.

When the Beis Hamikdosh stood, Yom Kippur saw the kiyum of the mitzvah of the Shnei Se’irim. The Cohen Gadol would place a lot on the head of each of two goats; one read “to Hashem” and the other “to Azazel” – according to Rashi, the name of a mountain with a steep cliff in a barren desert.

As the Torah prescribes, the first goat was sacrificed as a korban; the second was taken through the desert to the cliff and cast off.

The Torah refers to “sins and iniquities” being “put upon the head” of the Azazel goat before its dispatch. The deepest meanings of the chok, like those of all chukim in the end, are beyond human ken. But, on a simple level, it might not be wrong to see a symbolism here, a reflection of the fact that our aveiros are, in the end, foreign to our essences, extrinsic entities, things to be “sent away,” banished by our sincere repentance.

In 1934, when Otto Kahn died, Time Magazine reported that the magnate, who had been deeply dismayed at the ascension of Hitler, ym”s, had, despite his secularist life, declared: “I was born a Jew, I am a Jew, and I shall die a Jew.”

Mr. Kahn may never have attended shul for Kol Nidrei. But perhaps a seed planted by a hunchbacked humorist, and nourished with the bitter waters of Nazism, helped him connect to something of the declaration’s deepest meaning.

© 2019 Hamodia