The Satmar Rebbe and Rabbi Moshe Sherer had the same take on the question of whether or not anti-Israel sentiment cloaks antisemitism. To read what they had to say, please click here.

The Satmar Rebbe and Rabbi Moshe Sherer had the same take on the question of whether or not anti-Israel sentiment cloaks antisemitism. To read what they had to say, please click here.

Stripped of all of history’s dross, the fundamental struggle of humanity is between two views: The recognition of a Creator (and the resultant meaningfulness of human life) and the belief that life is the product of mere chance and, hence, essentially pointless.

It is the worldview-struggle between Klal Yisrael and Amalek, introduced at the end of this week’s parsha in a military showdown.

We read how the Amalekites attacked the Jews after our ancestors’ exodus from Egypt, and how Moshe Rabbeinu, from a distance, influenced the course of the battle.

“When Moshe lifted his arm, Yisrael was stronger; and when he lowered his arm, Amalek was stronger.” (Shemos 17:11)

The name Amalek, whose final letter is“kuf,” can be parsed as “amal kof” — the “toil of a monkey.” (Kuf and kof are spelled identically, and kof meaning monkey is found, in its plural form, in Melachim I, 10:22 and in Divrei Hayamim II, 9:21.)

Ki adam l’amal yulad — “For man is born to toil” (Iyov, 5:7). We humans are here l’amal, for toil, to work to rise above our base natures and serve our Creator according to His will. Our lives have ultimate meaning. This is the credo of Yisrael.

Amalek, by contrast, sees man as a mere product of chance happenings and random mutations, with no more inherent worth than any animal, including his closest “relative,” the ape.

Curiously, and perhaps significantly, only two creatures are able to lift their arms above their heads: apes and humans.

Might Moshe’s raised arms during the Amalek-Yisrael battle signify Yisrael’s anti-Amalek conviction, that there is a G-d in heaven?

Amalek, too, denying the divine, can raise its arms, but its gesture is meaningless. It is a monkey’s mere, and quite literal, aping of what Yisrael is doing when it raises its arms heavenward.

Amalek’s “toil” is amal kof, that of a monkey, using its arms only to swing from vine to vine, without any higher aim than getting from here to there.

The pan-historical Yisrael-Amalek struggle is thus a pitting of dedication to Hashem, signified in our parsha by Moshe’s raised arms, against the meaningless toil of human creatures who deny what being human truly means.

While we cannot know the identity of the Amalekites today, the philosophy identified with that people is everywhere around us. But Yisrael and its understanding of life’s meaningfulness will prevail in time.

© 2026 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Much attention has been given to the ascension of Zohran Mamdani to the mayoralty of New York City.

But whether the future of the left wing of the Democratic Party is more accurately presaged by the election of a radical as mayor than by the downfall of a progressive governor is far from clear.

To read what I’m referring to, please click here.

Chazal describe the Jewish people as a miracle. Our foremothers, for instance, were physically incapable, the Midrash informs us, of bearing children. Yet, despite the laws of nature, they did.

Jewish history, no less, testifies to the miraculous existence of Klal Yisrael. Despite the vicissitudes of our history, our repeated scatterings and exiles, and the insane but ever-present desire of some to wipe us out, we have persevered, and persevere, as a people.

The alpha-point of our peoplehood is in our ancestors’ exodus from Egypt, their leaving behind of their servitude to men for the holy calling of servitude to Hashem. And in this week’s parshah, we read of the preparation for doing that, which includes the first Pesach sacrifice and, perplexingly, the placing of some of the animal’s blood on each Jewish home’s doorposts and lintel — a ritual referred to as an ōs — a “sign” (Shemos, 12:13).

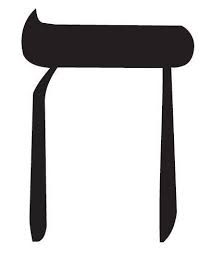

But ōs can also mean a letter of the aleph-beis, the Hebrew alphabet.

The celebrated 16th century Torah luminary, Rabbi Yehudah Loew ben Betzalel, the Maharal, famously associates the number seven with nature, and the next number, eight, with “above” or “beyond” nature – what we would call the miraculous.

Picture the Jewish doorways in Egypt just before the exodus. Imagine away the edifices themselves, leaving only the sign of the blood, in two vertical parallel lines along the doorposts and one horizontal one, above and connecting them.

The image is that, in ksav ashuris, of a ches, the eighth letter of the Hebrew alphabet.

© 2026 Rabbi Avi Shafran

A Substack post about evolution is here.

Future Substack post links won’t be posted on this site. So if you have interest in reading them each week, please subscribe (it’s free) to my Substack. Thanks.

.

An essay I wrote about the historic pattern of antisemitism appears at Religion News Service and can be read here.

Displeasure over Kevin Roberts’ refusal to distance the Heritage Foundation from Tucker Carlson has yielded something good: A boost to Mike Pence.

To read more about that something, please click here.

Only one of the Ten Plagues visited upon Par’oh and Mitzrayim elicits a declaration of guilt and admission of Hashem’s righteousness from the Egyptian leader.

“This time I have sinned,” Par’oh admits. “Hashem is the righteous One, and I and my nation are the wicked ones.” (Shemos 9:27).

It is the plague of hail. Why, of all the other punishments, that one?

What occurs is that the answer may lie in the Midrash brought by Rashi (ibid, 24), that each piece of hail contained a flame, and that water and fire “made peace with each other” in order “to do the will of their Creator.”

Par’oh was an idolater. The Egyptians worshipped the Nile and, according to historians, the sun. Idolatry entails choosing a “team” to be on. One can be on Team Nile, Team Sun, Team Water, Team Fire…

Monotheism entails the recognition that all the “teams” (elohos) are subservient to the one Creator of all the elements (Elohim).

Perhaps Par’oh was forced to confront and internalize that fact by having witnessed, during the plague of hail, the “partnership” of opposites.

Truth be told, we are all comprised of opposites: souls and bodies. Each has its own desideratum. The only way to “make peace” between them is endeavoring to fulfill the will of our Creator, which requires both elements to work together.

© 2026 Rabbi Avi Shafran

You can read my Substack offering “Dear Mayor Mamdani” here.

Some of Vice President Vance’s recent comments leave me underwhelmed. I elaborate here.