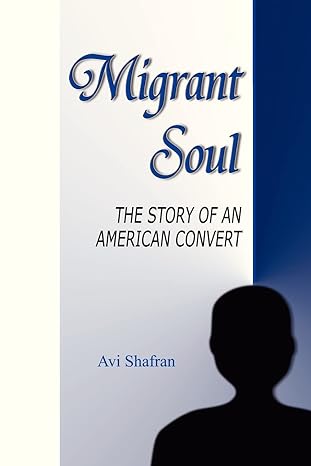

Mishpacha Magazine asked me to contribute, as part of a symposium, a short essay on the topic of a lesson I would want my children to internalize. The symposium was recently published, and my contribution is below.

(As it happens, although the below was written months before then end of my 31-year tenure as Agudath Israel’s director of public affairs, it turns out to be a most timely idea for me.)

A lesson that has become concretized in my life, and that I have sought to impart to my children (and to anyone else who will listen – the progeny are a captive audience) is what Rabi Akiva famously said when he found himself sleeping in the wild, with the candle he had lit blown out by the wind, his rooster alarm clock devoured by a cat and his donkey killed by a lion (Berachos 60b).

Namely, “All that the Merciful One does is for the good” – an attitude that reflected the motto of his teacher, Nachum Ish Gamzu, “This, too, is for the good.”

And when Rabi Akiva repeats that sentiment as well to the people of the nearby town as they, unlike him, were marched into captivity, he is reminding them of the same, even as they are experiencing great adversity. We may not see the good in what happens to us right away – or ever – but it is still for the good.

There’s nothing wrong with wishing for peace and calm and stability. But when adversity arrives, we can either kick and scream (to no avail) or seek to accept and come to terms with the challenge.

What began to teach me that lesson (though it took long to absorb it) was the knowledge that my father, a”h, as a teenager, was banished with other members of his Novardhok yeshiva by the Soviets to Siberia. Those boys could easily have felt hopeless. Yet they grew in unimaginable ways during their Siberian ordeal. And survived the war to marry and raise families. Families that raised families of their own…

And in my own life, although I never faced anything like Siberian exile, I saw how “bad” things could be good things well-disguised. Our family moved to new cities twice and each exodus was from a wonderful place, leaving me devastated to be leaving. In each case, the new city loomed depressingly.

And yet, each move turned out to be a great brachah. As did an unexpected seeming professional downturn, which I deeply bemoaned at the time but that I have come to see as a true blessing well-camouflaged.

The life lesson of understanding how good can lie beneath what seems its opposite is even reflected in halacha: “Just as one offers a blessing over good,” Chazal teach and the Shulchan Aruch codifies, “so does one offer a blessing over bad.”

I still need to fully internalize that truth; it’s one that needs constant chazarah. But I have experience born of having seen it realized. And I hope that my and my wife’s children will come to appreciate it as well.