A dear friend who had a secular upbringing and maintains an irreligious

outlook took issue, gently, if a bit cynically, with something I had written

for Aish.com, a website that reaches out to a broad swath of Jewish readers.

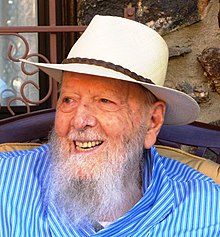

The article was about R’ Yosef Friedenson, a”h, the longtime editor of Dos Yiddishe Vort, the Yiddish-language

periodical published for many years by Agudath Israel of America. “Mr.”

Friedenson, as he preferred to be called, survived the Holocaust and was a keen

historian, meticulous journalist, eloquent speaker – and one of the nicest

people I have ever met. I had the pleasure of his company for some twenty years

in the Agudah national offices in Manhattan.

In my tribute to R’ Yosef, I included a story from his

recent, posthumously published collection of memories, “Faith Amid the Flames”

(Artscroll/Mesorah).

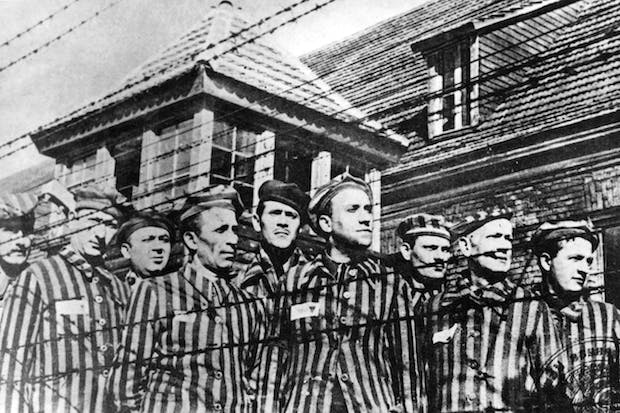

At the start of World War II, when Poland had been overrun

by the Nazis, ym”s, Mr. Friedenson

was a 17-year-old living with his family in Lodz. One day, two German soldiers

burst into the family’s apartment.

At one point, they demanded the teenager identify the

stately tomes on the bookshelf.

He had no reason to lie. “The Talmud,” he answered.

“At the mention of that word, they became like mad dogs,” Mr.

Friedenson recalled many decades later. “They threw the holy books on the floor

and trampled them, ripping them to shreds with their heavy boots.”

And when they had left, the young Yosef asked his father why

the Nazis had responded so viciously.

“They don’t hate us as a people,” was the response. “They

hate us because of our holy books. What is written in them is a contradiction

to all they stand for, to their outlook and corrupt mentality.”

My friend was suitably impressed with my description of Mr.

Friedenson. “Nice memory,” he e-mailed me, “of what sounds like a remarkable

man.”

But, he continued, “I’ll take a pass, out of respect, as to

the assertion that the Nazis hated Jews because of the content of books the former

almost certainly never read.”

My friend found it hard to imagine that the Nazis’ hatred

was qualitatively different from the antipathy of various ethnic or national

groups toward others. His materialistic outlook attributed no specialness to

our mesorah and, hence, no rationale

for how a movement based on power and paganism might find Torah a mortal threat

to its success.

I can’t prove otherwise to him, but shared something to buttress

Mr. Friedenson’s father’s observation, a memorandum discovered by the noted

Holocaust historian Moshe Prager, a”h.

It was sent on October 25, 1940 by the chief of the German

occupation power, I.A. Eckhardt, to the local Nazi district governors in occupied

Poland. In it, he instructs German officials to refuse exit visas to “Ostjuden,” Jews from Eastern Europe.

Eckhardt explains that these Jews, as “Rabbiner un Talmudlehrer,” Rabbis and Talmud scholars, would, if

allowed to emigrate, foster “die geistige

erneuerung,” spiritual revival, of the Jewish people in other places.

So it seems that it wasn’t just Jews whom the Nazis hated,

but Judaism. In fact, writing in 1930, Alfred Rosenberg, Hitler’s chief

ideologue, denounced “the honorless character of the Jew” – his take on the

idea of personal conscience and devotion to the Creator – as “embodied in the Talmud and in Shulchan-Aruch.”

The “spiritual renewal” that the Nazi memo author so feared,

baruch Hashem, despite the best evil

efforts of the movement he championed, has in fact come to pass.

Torah-committed Jewish survivors helped rejuvenate Jewish

life on these and other shores, rebuilding Jewish communal and educational

institutions and fostering shemiras

hamitzvos and, yes, Talmud study,

in new lands. The scope and enthusiasm of the Siyum HaShas is powerful evidence of that.

Daf Yomi, of

course, was introduced by Rav Meir Shapiro in 1923. It isn’t known how many

attended the first or second Siyum HaShas.

But, amazingly, right after the Holocaust, in 1945, thousands of Jews in Eretz

Yisrael, the Feldafing Dispaced Persons camp and New York united to mark the

third Siyum HaShas.

The 1968 Siyum at

the Bais Yaakov of Borough Park drew 300 people; by 1975, at the 7th

Siyum, five thousand celebrants gathered at the Manhattan Center; and, at that

gathering, the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah permanently dedicated the Siyum HaShas to the memory of the six

million Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

The 1990 Siyum

filled Madison Square Garden’s 20,000 seats. In 1997, the Siyum required both Madison Square Garden and the similar-sized Nassau

Coliseum.

In 2012, the 12th Siyum

Hashas filled MetLife Stadium with close to a hundred thousand Jews –

joined at a distance in countless other locales by thousands of others.

The Talmud and its

lehrers had emerged victorious.

Ironies abound on the path to that victory. Perhaps none,

though, as astonishing as the format of a new publication of “Mein Kampf” in its

original German, the first edition of Hitler’s rambling, anti-Semitic imaginings

to be produced in Germany since the end of World War II.

Intended for scholars and libraries, it is heavily annotated

to provide the elements of the screed with their necessary context.

The critical notes, however, are not presented in a

traditional manner. The academic team that prepared the edition decided for

some reason to instead “encircle” Hitler’s words with the deconstructing annotations.

Dan Michman, head of international research at Yad Vashem

museum in Israel, described how, as a result, the pages would appear.

They will, he said, “look like the Talmud.”

© 2019 Hamodia (in

shortened form)